How do you become the best distance runner in the world?

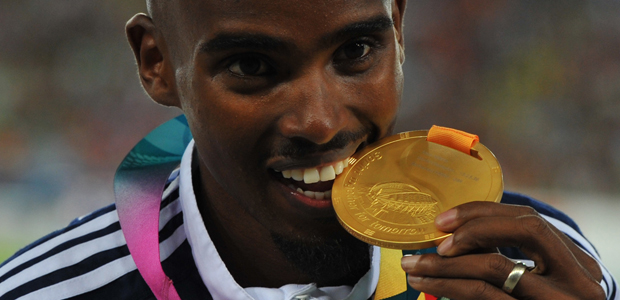

Moving to Oregon, sleeping in an air-thinning tent, and training come what may. Sports Reporter Keme Nzerem meets Mo Farah on his quest for distance running world domination.

Beaverton, Oregon, may well be the running capital of America, but it has the distinct feel of Blighty in the rain. That it has become a home from home for Britain’s best distance runner is probably just as well, for he’s had to accept the heavens open a hell of a lot here.

Mo Farah moved his family here last winter so he could try and find what he described as the “extra 1 or 2 per cent” he needed to become world number one.

This time last year Farah had established himself as the best distance runner in Europe, but he was still struggling against the best in the world – the East Africans.

Then he moved to the Pacific north west to work with renowned coach Alberto Salazar, and in four short months he went from good – to great. Yes, he was pipped at the line to the 10,000 metres gold at the Athletics World Championships this summer – but learnt from his defeat to win the 5,000 metres a week later. So what changed?

American life

His all new, all American life? Well yes, in a manner of speaking.

British distance athletes typically use the altitude training facilities in the highlands of Kenya or Pyrenees to isolate themselves from the distractions of daily life. And the thin mountain air encourages their bodies to produce more oxygen carrying red blood cells.

But Farah’s new coach, who is based at the Nike campus, can deliver most of that with his hi-tech training facilities a few miles outside the state capital, Portland.

A combination of secret underwater treadmills, zero gravity running machines, and air thinning sleeping tents have helped slash Farah’s personal bests by huge margins – taking 40 seconds off his 10k record.

Some have queried how such a rapid improvement can be possible – questioning Mr Salazar’s behind closed doors methods. Some years ago WADA – the world anti doping body – even considered banning some of his technology.

But Mr Salazar is bullish in his – and his athlete’s – defence.

“We are doing stuff other countries don’t know about – and it gives us an advantage,” he said.

But Mr Salazar insists there is no funny business going on.

“We all know what’s right and what’s wrong. [But] however you can train better, that’s great.”

And while we’re on the topic, Mr Salazar broaches the subject of performance enhancing substances. It is, he said, “just something we would never come close to doing – it’s not an option – we are completely clean about everything we do.”

And Farah, he says, was tested more than anyone.

“I’m gonna guess Mo was tested 20 times last year,” he said.

As we finish our interview Nike employees trudge in from their lunch breaks – ruddy faced and swathed in mud to their knees. The ritual Nike lunchtime run. It’s still pouring outside.

Which, in a way, brings us back to the weather. Because any athlete will tell you there are times when you just don’t fancy getting out in the cold, in the rain. And here in Portland, it can fall for days on end. But if you don’t get out and train come what may – you may as well be running backwards. And Mo Farah, it would seem, is full steam ahead.

He goes to Kenya the day after Christmas for real high altitude training. Then he races in Glasgow. He’ll travel to Istanbul for the World Indoor Championships this spring.

Then the small matter of a wee sports event in London next summer. And right now there’s no question – Farah is the man to beat.

-

Latest news

-

Fans react to football clubs increasing season ticket prices4m

-

‘We’re still a long way from justice’, says infected blood scandal victim5m

-

Infected blood scandal: Victims set to receive billions of government compensation7m

-

Iran’s president and foreign minister missing after helicopter crash3m

-

Yungblud launches his own affordable music festival5m

-