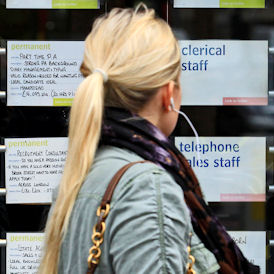

Unemployment hits women hardest

Unemployment figures published today reveal that one in five young people are unemployed, but women across all age groups are bearing the brunt of joblessness.

The Office of National Statistics’ labour market statistics bulletin reported that the number of out of work 16-25-year-olds reached 963,000 in the three months to February – an increase of 12,000 on previous figures published in January.

That the number of young people out of work remains high has renewed fears that a ‘lost generation’, unable to find work in the crucial early stages of their working lives, will emerge from the aftermath of the recent recession.

Unemployment hit the youngest section of this age group the hardest, with the number of unemployed 16 to 17-year-olds reaching 218,000 – an increase of 14,000 on the quarter. However, a TUC spokesman told Channel 4 News: “We wouldn’t draw too many conclusions from this younger age group, as the picture is more mixed.” A more reliable indication can be gleaned from the number of out of work 18-to-24-year-olds, which fell by 2,000 on the quarter to 745,000.

Indeed, overall, the figures for this age group are actually a slight improvement on those earlier this year, which showed the total number of unemployed young people to have reached nearly one million – the highest level of youth unemployment since records began in 1992. And across all age groups, the unemployment rate reduced from 8 per cent to 7.8 percent.

However, Ian Brinkley, director of socio-economic programmes at The Work Foundation, said that although these were “better figures than expected”, caution was necessary given that “serious underlying structural problems remain”. He pointed to unemployment among young people and also long-term unemployment among the over 50s as being cause for concern.

Women workers worst affected

In both these age groups, unemployment figures for women are higher than those for men. As ONS spokesman David Bradbury told Channel 4 News: “The pattern in recent months is that things are better for men and worse for women. This is different to the height of recession when men were most affected.”

Over the course of the last year, as the UK emerged from recession, female unemployment went up by 64,000, Mr Bradbury said, while male unemployment went down by 69,000. Click here for more on those figures.

‘Women are now re-entering the labour market in larger numbers in the hope of finding work’ – Ian Brinkley, The Work Foundation

The TUC told Channel 4 News: “A recent TUC analysis found that since the recession young female joblessness had nearly trebled in the South West, and more than doubled in the North West, Yorkshire, West Midlands, South East and Scotland. With jobs in the public sector – a key career route for young women – starting to go over the course of the year, the figures are set to get even worse.”

TUC General Secretary Brendan Barber said: “Female unemployment has been rising many months and the number of women out of work is at a level last seen in the late 1980s. What’s particularly worrying is that these figures come before public sector job losses really start to bite.

“With hundreds of thousands of jobs set to go in local government alone – where three quarters of staff are female – there are real fears that rising female joblessness could increase in pace.”

Ian Brinkley, spokesman for The Work Foundation, said: “Women’s employment has started to recover, but women’s unemployment still went up, in contrast to men. One reason is that women are now re-entering the labour market in larger numbers in the hope of finding work. But the experiences of older and younger women differ significantly. Unemployment among young women between 18 and 24 is 16 per cent compared with just over three per cent for women over 50.”

Concern that public sector cuts will have a disproportionately adverse affect on women have already been voiced. According to the Fawcett Society, which campaigns and researches for issues of relevance to UK women, the majority of savings in the budget would ‘come from women’s pockets’ through the freezing of benefits and public sector pay freezes.

Up to 80 per cent of women in public sector jobs at risk

The Society, who issue a report tomorrow on the impact of the budget and the latest employment figures, argue that cuts in public sector funding and public sector jobs affect women disproportionately because women form the bulk of the workforce in the public sector. And within areas such as local government and the NHS (where women comprise around three quarters of the workforce) women are often concentrated into the lower-grade and insecure jobs which often take the first hit. For this reason the Fawcett Society estimate the actual percentage of women at risk from public sector cuts to be nearer 70 per cent, while the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development puts that figure at closer to 80 per cent.

Private sector no antidote

Anna Bird, spokesperson for the Fawcett Society told Channel 4 News that private sector employment is not ‘an antidote’ to public sector cuts. She points out that given the private sector has historically lagged behind the public sector in the pay gap between men and women, is slower to promote women at the top, and employs only 40 per cent of women in its workforce, even if jobs are created for women, the quality of those jobs may be somewhat poorer than their public sector counterparts.

As Mr Brinkley noted: “Looking over the recovery so far women have been adversely affected by two trends – the drop in employment in the public sector and parts of the banking sector and weak employment growth in more traditional industries such as retailing and hospitality. These sectors all have above average shares of female employment. In contrast, manufacturing and high tech and professional services have seen some recovery in employment and these sectors all employ large numbers of men.”

-

Latest news

-

Yungblud launches his own affordable music festival5m

-

Why these Americans want to quit their state9m

-

Company behind infected water outbreak are ‘incompetent’ says local MP5m

-

Israeli forces push deeper into Northern and Southern Gaza4m

-

India’s ‘YouTube election’: Influencers enlisted to mobilise youth vote6m

-