The deficit

In George Osborne’s first budget in June 2010, the prediction was that “the cyclically-adjusted or structural current deficit will be eliminated by 2014-15”.

The national debt was expected to peak at 70.3 per cent of GDP in 2013-14.

The latest forecasts say the deficit will now not be eliminated until 2017/18 and public sector net debt will peak at 80.4 per cent of GDP in 2014-15 – about double its pre-crisis level.

The deficit has been halved as a percentage of GDP, but not in cash terms. So the government has barely achieved half the deficit reduction it set out to do.

The Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) says: “Out of 31 advanced economies, only Japan will have higher structural borrowing than the UK in 2015. This is despite the UK having done the seventh-largest fiscal consolidation since the crisis began.”

Slowest recovery

Mr Osborne has made much of the fact that the IMF predicts that the UK would enjoy higher GDP growth than the rest of the G7 economies (the US, Canada, Japan, Germany, France and Italy) in 2014.

But this is a recent phenomenon. As this government graph shows, Britain (the blue line) lagged behind other major economies for years after the recession and has only just caught them:

And GDP growth has recovered more slowly after the most recent recession (purple, bottom) than any other in recent decades, according to the Officer for National Statistics (ONS):

Living standards

Incomes have also been historically slow to recover after plummeting in real terms after the financial crisis, mainly because wage growth has lagged behind inflation for the longest spell in modern history.

Again, there has been some recent good news for Mr Osborne, in that one measure he has selected – real household disposable income per head – and another measure used by the IFS show that incomes have just about returned to their pre-crash levels.

Again, the rate of improvement since the recession has been markedly worse than in previous recoveries.

All in it together?

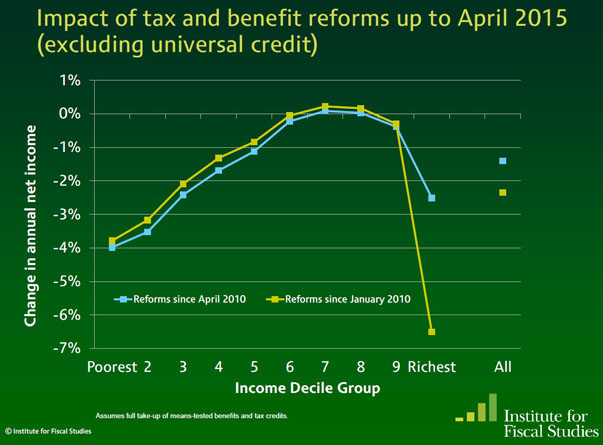

IFS research suggests that not every part of society has borne an equal burden.

Pensioners’ incomes have actually grown since 2007/08, while people in their 20s have taken the biggest hit.

The IFS also thinks that it’s the very poorest who have seen the biggest fall in their annual income thanks to all the tax and benefit changes made by Mr Osborne (blue line).

It has to be said the Treasury figures, calculated using a different methodology, do not support this view.

Low paid jobs

There is no dispute that employment has risen under the coalition, with the rise in private sector employment more than cancelling out cuts to the public sector workforce.

Critics of the government often query the quality of the jobs created under the coalition – but there has been little change in the relative size of the self-employed, part-time or temporary sectors, and the jury is still out on whether the use zero-hours contracts have gone up.

There are however, real questions about the continuing prevalence of low-paid jobs.

The Resolution Foundation calculates that 22 per cent of employees, or around 5 million people – were earning less than less than two thirds of median hourly pay in 2013.

This has consequences for how much tax the chancellor can expect to rake in, among other things. Last year the OBR blamed a rise in low-paid work for lower-than-expected income tax receipts.

Consumer debt

The Conservative economic strategy, published just before the last election, slammed Labour for presiding over “unsustainable consumer borrowing on the back of a housing bubble”.

High levels of consumer debt and fears of another housing bubble have never really gone away.

The OBR forecasts that household debt will climb steeply from this year and that households are saving less of their income than they were at the last election.

The ratings agency Fitch, which downgraded the UK from AAA to AA+ in 2013, warned last year that “recent rapid increase in the house price-to-income ratio, in particular in London, could lead to excessive leverage if supported by unsustainable lending practices”.

Safeguarding Britain’s credit rating was, incidentally, the first of the eight benchmarks against which Mr Osborne urged voters to hold the Conservatives to account before the 2010 election.

Productivity

Labour productivity – the amount of goods and services produced per hour – has been “exceptionally weak” since the crash, according to the Bank of England.

Once more, the fall in productivity (orange) has been deeper and last longer than after any post-war recession, the Bank says. And Britain is seriously lagging behind international competitors.

Lack of productivity growth is something that prompted the OBR to conclude gloomily last year that “it remains difficult to judge when the economy will fully recover from this post-crisis hangover”.

Exports

Mr Osborne has put boosting exports at the heart of his economic strategy, but the figures have been disappointing.

In 2012 the chancellor said he wanted Britain’s business to double exports to hit £1 trillion by the end of the decade. But exports fell to below half a trillion in 2014 and Britain’s overall trade deficit was bigger than it was in 2010.

The lastest OBR forecasts suggest we will fall woefully short of the £1 trillion target, with exports reaching perhaps £617bn by 2020.

And Britain’s export market share is predicted to continue to fall.