“Under David Cameron working people are £1,600 a year worse off.”

“Under David Cameron working people are £1,600 a year worse off.”

Labour Party tweet, 17 January 2015

The background

Labour has been arguing for some time that there is a “cost of living crisis” in Britain, with working people left out of pocket to the tune of £1,600 a year under the coalition.

But the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) has just published a report showing that living standards have bounced back to their pre-crisis levels.

Does this destroy Labour’s biggest line of attack against the coalition’s economic record?

The analysis

Labour’s numbers are all about real wages – average earnings adjusted for inflation.

The party used to stand this up by using official statistics on average weekly earnings and the RPI measure of inflation.

The trouble is that RPI is becoming increasingly discredited as an accurate measure of inflation. It was stripped of its status as an official statistic, and Paul Johnson of the IFS, among others, have said it should be abandoned.

Somewhat in the manner of a Countdown contestant, Labour now gets to the same number by a different route. They have abandoned RPI inflation in favour of CPI and use different figures for pay from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings.

Using this methodology, we can say that average annual gross pay fell by £1,668 in real terms between 2010 and 2014.

So far so good for Labour. But this isn’t the whole story.

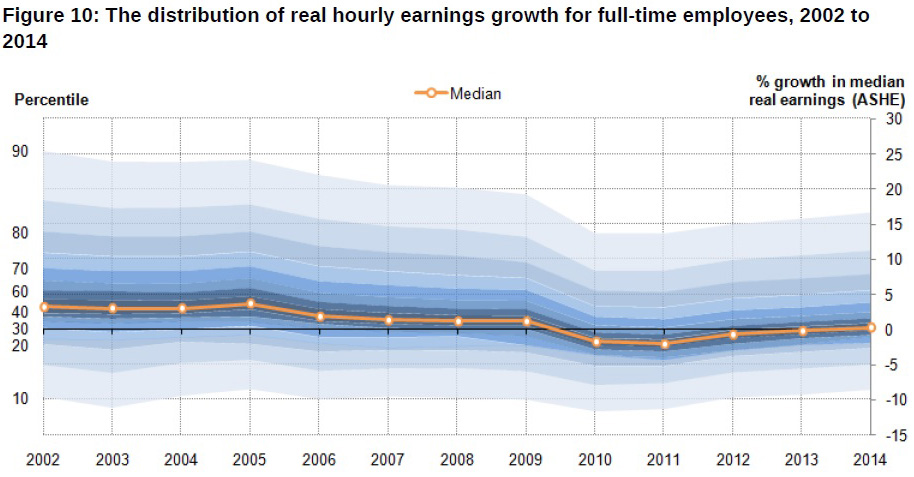

What Ed Miliband isn’t telling you is that earnings began to stagnate on Labour’s watch, in the mid-2000s, long before the global financial crisis and after decades of steady growth. You can see the slowdown in growth in this ONS graph:

Some of the the biggest falls in real wage growth happened on Labour’s watch too – in the wake of the 2008 crash but before David Cameron became prime minister.

Few economists would blame these trends on party politics. The IFS puts it like this: “It would be misleading to attribute all trends in living standards that occurred before May 2010 to Labour and all trends thereafter to the coalition.”

So far we’ve been talking purely about pay. But that may not be the best measure of cost of living.

Household income

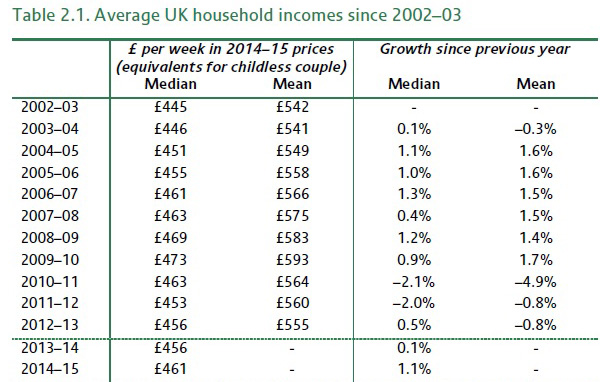

Today’s report from the IFS covers a wider measure of household income, which counts income from self-employment, pensions, benefits and tax credits on top of wages.

It appears that total average incomes have not fallen as sharply as wages, and have bounced back quicker:

If he were using IFS figures, Mr Miliband would only be able to say that people are £2 a week worse off in real terms now than they were in 2010/11.

(A big caveat here is that these are median average figures, and there are huge variations between different groups of people. Pensioners and people with children have done better than others under the coalition, while people aged 22 to 30 have seen their income fall the most since the recession.)

It’s true, as the IFS says, that incomes have recovered more slowly than in the aftermath of previous recessions – but then we haven’t seen the same levels of unemployment either.

Some economists think there may be a straightforward trade-off here: you can either have higher wages and fewer jobs in a recovery, or more people in work with depressed wages.

Professor Paul Gregg, who co-authored this 2012 study into the relationship between trends in unemployment and wages, told us: “The government is quite keen to talk about unemployment and the opposition wants to talk about wages. They are two sides of the same coin.”

Clearly, that puts Labour’s “cost of living crisis” rhetoric in a rather different light.

The verdict

Labour’s point about real wages falling substantially over the coalition period is a valid one, and they can still stand up their figure of people being £1,600 worse off a year – but only if they are talking about pay, not income as a whole.

And they don’t recognise that falling wages may be the price we are paying for relatively low levels of unemployment.

If wages continue to rise above inflation this will be less fertile ground for Labour. Average real wages have now risen every month for the last four months. (This has mostly been driven by plummeting inflation, and could be temporary.)

Today’s analysis from the IFS also shifts the emphasis from earnings alone to a broader measure of household income.

The suggestion is that incomes have now bounced back to their pre-crash levels, although whether you personally feel better off will probably depend heavily on your age and personal circumstances.