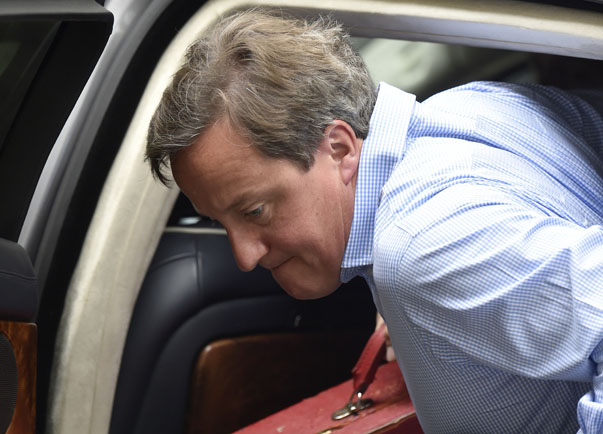

David Cameron had to cut short a family holiday yesterday to take charge of Britain’s response to the jihadi insurgency in Iraq.

The prime minister was two days into a break in Cornwall when he returned to Downing Street, as police and intelligence services try to identify the English-accented Islamic State terrorist who appears to have murdered US journalist James Foley.

Downing Street said the PM would return to Cornwall on Friday but would continue to receive regular updates and briefings.

Mr Cameron has faced criticism in some sections of the press over the number of holidays he takes.

Meanwhile, backbench MPs from all parties as well as Lord Dannatt, the former head of the Army, have called for all parliamentarians to have their summer holiday interrupted to debate the crisis.

Should politicians rush back to Westminster at times of crisis? And what happens if they don’t?

Chillaxing

Several newspapers have criticised the number of holidays Mr Cameron has taken since becoming Prime Minister in 2010.

It’s true that he has been on 15 breaks since the last general election, three of them this year. Cornwall is his favourite destination.

Mr Cameron has robustly defended the practice of taking regular time off, saying: “I’m a great believer that politicians are human beings and they need to have holidays.

“If you don’t think politicians ought to have holidays, I think you need to have a serious think.”

Similar criticism has dogged US President Barack Obama, who has taken trips about as often as Mr Cameron – 20 since entering the White House in 2009.

But according to CBS News correspondent Mark Knoller, Mr Obama’s predecessor George W Bush had taken 58 breaks at the same point in his presidency.

Mr Cameron said this week: “Wherever I am in the world, I am always within a few feet of a BlackBerry and an ability to manage things should they need to be managed.

“And indeed as I have done on I think almost every holiday that I have enjoyed over the past few years, I am able to return instantly should that be necessary.”

BlackBerry has seized on the free publicity by suggesting that its smartphones are the natural choice for security-conscious world leaders.

But Mr Cameron slightly spoiled the high-tech image by telling the Western Morning News he sometimes experienced signal failure in Cornwall while dealing with crises on the telephone:

“As I go down a hill into Polzeath, I know exactly which bit of the road I lose my signal. So it is a problem. I know where to go to get a signal, but it can be very frustrating.”

It’s true that Mr Cameron does have a record of cutting holidays short to deal with crises. He returned early from a trip to Portugal earlier this month to respond to the humanitarian emergency in northern Iraq.

Last year he came back early from another trip to Cornwall amid calls for Britain to intervene in Syria. In 2011 it was the collapse of Colonel Gaddafi’s regime in Syria that cut short the prime minister’s summer holiday.

Chain of command

Downing Street’s official line is that: “The prime minister is always in charge.” In other words, Mr Cameron does not delegate his decision-making duties to anyone else while out of the office.

He himself has said: “I always make sure there are senior ministers on duty in Westminster but I don’t hand over the government to a deputy.”

That has not stopped the media suggesting that the UK government is “rudderless” at moments when Mr Cameron and the deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, go on holiday at the same time.

According to current cabinet rankings, the next most senior minister after Mr Cameron and Mr Clegg is William Hague, who was made first secretary of state after the recent reshuffle.

The chancellor, home secretary and foreign secretary come next, in that order, but it’s not clear what, if any, effect these rankings have on the actual process of making policy decisions.

Unlike the United States, Britain does not have an official protocol designating who is in charge if an accident should befall the prime minister of the day.

The backbench Conservative MP Peter Bone is attempting to pass a bill laying out what the order of succession should be “in the event that a Prime Minister is temporarily or permanently incapacitated”.

Recall of parliament

Should all MPs have to return to Westminster in the summer recess at times of crisis?

Again, there is no clear protocol. Only the speaker of the house of commons can order a recall, but he does so “after receiving representations from ministers that the public interest requires it”.

In practice, this means that the prime minister decides to recall parliament and the speaker announces it. There’s no definition of what kind of crisis should trigger a recall – parliamentary rules simply state that it should be in “the public interest”.

Over the past 20 years MPs have been asked to return in response to the 9/11 attacks, the deaths of the Queen Mother and Margaret Thatcher, the 2011 riots, revelations about phone hacking by newspapers and events in Iraq and Syria.

There is a recent precedent for governments to seek a parliamentary vote before sending the armed forces into action.

But there is no constitutional obligation for the government to consult parliament before deploying UK forces in military action overseas. The authority to send troops into battle is covered by royal prerogative powers.

Technically, Mr Cameron could still have ordered military action against the Assad regime even after the government was defeated in a commons vote last year. But he chose not to override the will of parliament.

Similarly, ministers could order strikes against militants in Iraq without seeking parliament’s approval, but recent precedent suggests they are unlikely to do so.