In the wake of the MPs’ expenses scandal, the three main parties all backed plans to give constituents the power to kick misbehaving MPs out of office between elections.

Under the existing rules, members of parliament can be convicted of a crime and jailed for 11 months, but voters might have to wait years until the next general election to get rid of them.

The coalition announced today that voters will get new powers to trigger a by-election if a local MPs is guilty of serious wrongdoing.

But the probable detail of the legislation has not pleased leading campaigners.

Conservative backbencher Zac Goldsmith called it a “cynical stitch-up”. Unlock Democracy called the government proposals a “watered-down version of recall”.

Critics from Left Foot Forward to the right-of-centre Taxpayers’ Alliance have also queued up to write the recall bill off as a fudge.

Why the anger?

Mr Goldsmith and others are proponents of a broader, more simple form of recall than the one being proposed by the government.

The MP for Richmond Park & North Kingston wants voters to be able to call for a by-election for any reason they see fit. If a certain percentage of constituents sign a petition, there is a local referendum on whether the MP should be recalled.

If more than half say yes, there is a by-election and the MP will be sacked if he or she loses.This is sometimes called “full recall”, but FactCheck prefers the term Total Recall in honour of Arnold Schwarzenegger, who became governor of California after a recall election.

The government wants something much narrower. Constituents will get the chance to sign a petition if the House of Commons decides one of its members is guilty of serious wrongdoing or if an MP is jailed for less than 12 months (a sentence of more than a year already means you lose your seat under the Representation of the People Act).

It’s the involvement of MPs that is vexing Mr Goldsmith and like-minded critics the most. They don’t think parliament should be able to oversee the petition process – the power of recall should be entirely in the hands of the voters.

The coalition plans also do away with the referendum stage. If 10 per cent of constituents sign the petition (not 20 per cent, as Mr Goldsmith suggests) over eight weeks, there will be a by-election.

Do voters want the right to recall MPs?

Yes, it’s an extremely popular idea, according to one YouGov poll.

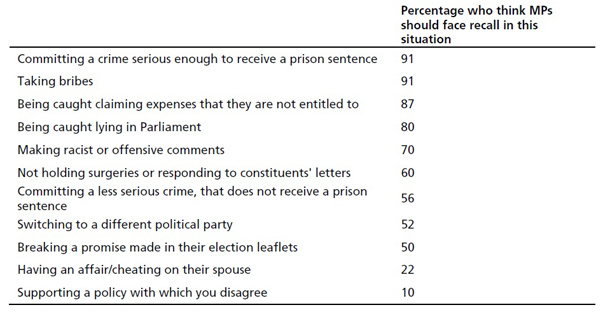

Some 79 per cent of 1,723 adults surveyed agreed that sacking MPs guilty of serious wrongdoing was a good idea. Asked what kind of behaviour should trigger a petition, some 91 per cent cited a crime serious enough for a prison sentence.

But voters also listed a number of other misdemeanours they would like to be able to recall MPs over: not holding surgeries or writing back to constituents (60 per cent); switching political allegiance (52 per cent).

Will people get what they want?

Not entirely. The current proposals will leave it up to a committee of MPs to decide whether their fellow politicians to decided whether a complaint against them is “serious wrongdoing”.

The government has never defined in draft legislation what this will actually mean, but the likelihood is that only serious breaches of parliamentary conduct will count.

This might cover financial wrongdoing like making false expenses claims, but it would almost certainly not cover: breaking promises to the electorate; disappearing from work to go on holiday or a reality TV show; ignoring constituents and failing to hold surgeries; jumping ship to a different party.

In other words, many of the things a significant number of people think ought to trigger a petition – according to that YouGov poll – won’t.

On the other hand, a prison sentence will automatically trigger a petition, with parliamentary committees having no say in the matter, and that is the issue that bothers most people who took part in the poll.

Is this a broken promise?

We’re not sure today’s announcement is technically a breach of promises made by the coalition partners.

The Conservative manifesto promises to “introduce a power of ‘recall’ to allow electors to kick out MPs, a power that will be triggered by proven serious wrongdoing.

The Lib Dems said: “We would introduce a ‘recall’ system so that constituents could force a by-election for any MP found responsible for serious wrongdoing.” They didn’t give any more detail.

The coalition agreement says: “We will bring forward early legislation to introduce a power of recall, allowing voters to force a by-election where an MP is found to have engaged in serious wrongdoing and having had a petition calling for a by-election signed by 10 per cent of his or her constituents.”

That was written in 2010, so the legislation certainly wasn’t brought forward early, but the wording is vague enough for the government to say that today’s announcement is a fulfillment of this promise.

Obviously this pledge doesn’t make it clear that MPs would end up playing a leading role in the process, but it doesn’t rule out the possibility either.

Any other criticisms of the plans?

Plenty. Some critics don’t think a prison sentence should automatically trigger a petition. What about MPs who end up in jail on a point of principle, in the tradition of Gandhi or Martin Luther King?

Ulster Unionist and Sinn Fein MPs have been imprisoned for civil disobedience, and in 1991 Labour MP Terry Fields got 60 days for refusing to pay his poll tax.

The nature of protests like this won’t be taken into account under government plans.

Some critics say the 10 per cent threshold “feels low” if the government wants to avoid local opposition groups launching vexatious campaigns to oust MPs simply because they disagree with their policies.

It should be said that the government has listened to some technical criticisms of how the actual petition would be handled and has amended its original plans to make it easier for people to vote.

Do we really need recall?

Although some kind of right to recall MPs enjoys broad cross-party support, there are arguments to be made against it too.

Experts who gave evidence to the Commons political and constitutional reform committee pointed out that there is no exact definition of what an MP is supposed to do, so it is difficult to decided what constitutes wrongdoing.

Politics professor David Judge from the University of Strathclyde pointed out that the proposals might give too much weight to the idea of the MP acting for a specific locality, when in reality our system isn’t really about local representation.

Most people vote for a party, not an individual, and the majority don’t even know the name of their local MP, he says.

Professor Judge also cites another opinion poll that suggests people think things have improved since the expenses scandal. He notes that the old expenses regime has been reformed and corrupt MPs have been removed from office without the need for recall.

The evidence from other countries who use recall protocols is mixed too.

While Zac Goldsmith is right to say that vexatious abuses of the various systems appear to be rare, some politicians in the US and Canada’s British Columbia say they spend too much time worrying about their popularity with the threat of recall hanging over them.

The overwhelming picture, though, is that politicians are rarely successfully removed from office by petitions. Mr Schwarzenegger is only the second governor in US history to be elected after a recall vote.

And there remains some controversy about the campaign to oust the bodybuilder and actor’s predecessor Gray Davis, who was blamed for California’s energy crisis before the role of companies like Enron was widely known.