The claim

“The overall recovery from the bank interventions is in the order of £14bn of magnitude.”

“The overall recovery from the bank interventions is in the order of £14bn of magnitude.”

Harriet Baldwin, 11 June 2015

The background

Labour’s decision to pump tens of billions of pounds worth of taxpayers’ money into the crisis-hit banking sector between 2007 and 2010 is still hugely controversial.

Cracks first appeared in the global financial system in summer 2007, when banks started to take heavy losses on risky mortgage debt.

The then chancellor Alistair Darling used government money to prop up the UK banking sector in a series of interventions, the most dramatic of which was to pump £45bn of state funds into ailing RBS by buying an 83 per cent stake in the bank.

The government said at the time that this was a temporary move. The taxpayer would eventually sell its shares in RBS and Lloyds – the other teetering giant – getting some or all of the money back, depending on share prices.

Today the Treasury suggested that the deal is likely to turn out much better than anyone expected. Rather than losing tens of billions, the taxpayer will ultimately profit to the tune of about £14bn.

On face value, it looks like a piece of astonishing good news. But there’s a catch.

The analysis

The government has commissioned an independent report from financial advisers Rothschild on the eventual cost of bank bailouts.

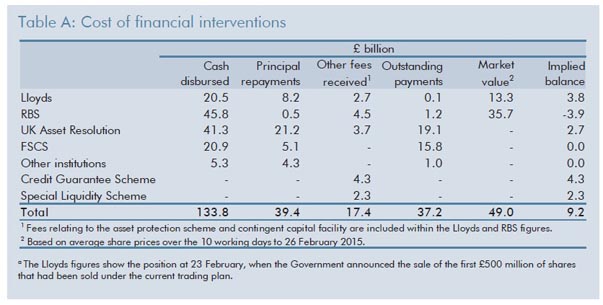

The firm’s findings are summarised in a table:

So the government has injected £107.6bn into the whole sector, £45.8 of which has gone to RBS. But it hasn’t all been one-way traffic. Money has been trickling back into Treasury coffers (repayments, cash and fees received).

And if the government sold off all its shares in Lloyds, RBS and UKAR (the holding company that manages the assets of Bradford & Bingley and Northern Rock), it could expect to rake back around £51bn, based on current share prices.

Of course prices go up and down all the time, and all the shares won’t be sold in one go, so this valuation will change.

Note that if all the shares in RBS were sold off to private investors, the taxpayer would be looking at a net loss of £7.2bn, based on what we have put into RBS and what we can expect to get out.

But the government is keen to look at all the interventions, not just RBS, and overall there is a predicted surplus, a gain to the taxpayer of £14.3bn.

This is much better than the gloomy prediction in the 2009 budget that there would be a net loss of £20bn to £50bn.

We don’t have any reason to doubt Rothschild’s numbers, and the “cash in – cash out” methodology is similar to that used by the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in its latest Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

Here is the OBR table:

The OBR isn’t quite as optimistic as Rothschild, but it still predicts a net surplus for the taxpayer of £9.2bn.

Here comes the big “but”

The government didn’t just have 100-odd billion sloshing around to bail out the banks. It had to borrow the money. It did so by issuing interest-bearing government bonds called gilts.

So the Treasury has been paying out interest to investors on the gilts for about seven years now. How much has this cost?

The Rothschild report doesn’t tell us. The only reference is in a brief footnote: “Stated before the cost of funding the interventions.”

Andrew Tyrie, Conservative chairman of the Treasury select committee, asked the Treasury Minister Harriet Baldwin about this today in parliament.

He said: “I note that a footnote makes clear that this excludes the cost of funding. I’d be extremely grateful if you could say what the cost of funding is and what that number would be were it included in the table?”

Ms Baldwin did not really answer the question. She replied: “At the end of 2009 the estimate was that the cost of bank interventions would range between £20 billion loss and £50 billion loss.

“As of last week, the Rothschild report estimates that situation has completely turned around, that the overall recovery from the bank interventions is in the order of £14bn of magnitude and the overall cost of funding on our Treasury issuance is at record lows thanks to the prudent economic management of my right honourable friends.”

But there is an estimate available. The OBR included it alongside the table we have just looked at, saying: “These figures exclude the costs to the Treasury of financing these interventions, and any offsetting interest and dividend receipts.

“If all interventions were financed through debt, the Treasury estimate that additional debt interest costs would have amounted to £22 billion to date. The Treasury has also received around £5 billion of interest over the same period.”

This looks like there has been an additional cost to the taxpayer of about £17bn, which for some reason has not been covered in government-commissioned Rothschild report.

Of course, if we include that loss of £17bn in the final balance sheet, it more than cancels out the £14bn surplus ministers are keen to talk about, and means the taxpayer has suffered a net loss overall.

The verdict

It seems fair to conclude that the government isn’t quite telling us the whole story here.

The cost of the borrowing that financed the bank bailouts appears to wipe out the gains being publicised today and leave the taxpayer in the red.

In fairness, it has to be said that the outcome still looks much better than the £20bn-£50bn losses predicted in 2009.

We can only speculate as to why the government left funding costs out of its calculations, and why the minister wasn’t able to put her finger on a number when challenged in parliament, even though a figure was published by the OBR several months ago.

Does this mean the government disputes the OBR’s numbers? We have asked the Treasury to comment and will update if they come back with something.

UPDATE: after this was published, a Treasury spokesman gave us the following statement:

“The methodology used by Rothschild is the same as that used by the independent Office of Budget Responsibility in their analysis of the government’s interventions in the banking sector, and by the US Treasury.

“The Rothschild report clearly sets out that taxpayers can expect to get back £14 billion more than they put into the banks, if you take into account the sales the government has authorised so far, the fees the government has received, the outstanding payments, and the value of the remaining shares.”