Who will rid David Cameron of these troublesome priests? First the country’s most senior Catholic clergyman, Archbishop of Westminster Vincent Nichols, said coalition benefits cuts were a “disgrace”.

Then 27 Anglican bishops and 16 other Christian leaders signed a letter to the Daily Mirror linking the increasing popularity of food banks and a rise in cases of malnutrition to changes and failures in the welfare system.

The clerics wrote: “We call on government to do its part: acting to investigate food markets that are failing, to make sure that work pays, and to ensure that the welfare system provides a robust last line of defence against hunger.”

Are significant numbers of people really going hungry in Britain and has the government made it worse? (All the claims are from the letter signed by the church leaders.)

“Half a million people have visited foodbanks in the UK since last Easter”.

The Trussell Trust, by far the biggest operator of food banks, has given us its latest stats on how many people it is feeding across the UK.

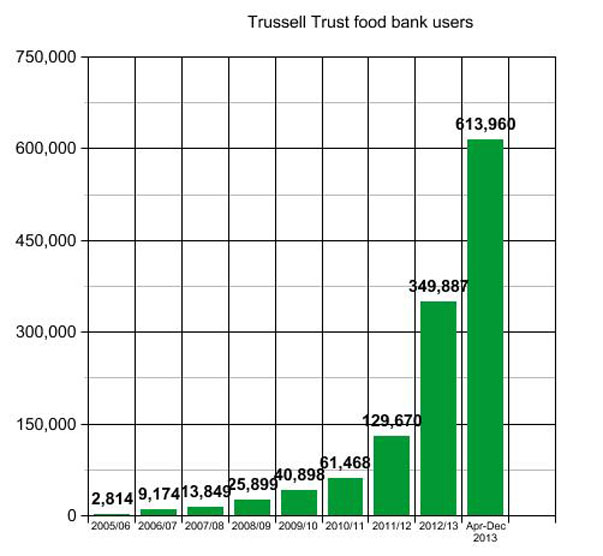

In the nine months from April to December 2013, some 613,960 people were given three days’ worth of emergency rations by a Trussell Trust food bank.

That compares to 349,887 people fed in the whole of 2012/13 and 129,670 in the previous financial year.

We noted in an earlier FactCheck that the growth of food banks pre-dates the coalition government and the financial crisis, and David Cameron has correctly stated in the past that their use went up tenfold under the last Labour government.

This graph shows the growth in the numbers of individual users since 2005/06 and puts the scale of recent rises in perspective.

The Daily Mail did a kind of FactCheck of its own today and pointed out that these numbers could include the same individuals coming back for food multiple times.

The Mail put it like this: “The bishops do not know if 500,000 people have visited food banks once, or 50,000 have gone 10 times.”

The Trussell Trust told us this was “incredibly misleading”, saying: “Many people only need one voucher, and the vast majority of people need less than three foodbank vouchers in a year.

“Since August, 45 per cent of Salisbury foodbank’s clients came to the foodbank once; 24 per cent twice; 8 per cent three times; only 22 per cent needed more than three vouchers.”

And the Trussell Trust isn’t the only game in town. There are other independent food banks, though figures for them are sketchy.

A joint report by Church Action on Poverty and Oxfam last year found that at least half as many people again were being helped by non-Trussell Trust organisations, and estimated that more than 500,000 people were reliant on food aid.

“Over half of people using foodbanks have been put in that situation by cut backs to and failures in the benefit system, whether it be payment delays or punitive sanctions.”

“Over half of people using foodbanks have been put in that situation by cut backs to and failures in the benefit system, whether it be payment delays or punitive sanctions.”

Again, the Mail takes issue with this, but we think the form of words used here is substantially true.

The Trussell Trust makes of note of the reasons given by users for why they need food aid.

The most popular reason is “benefit delays”, the second is “low income” and the third is “benefit changes” – cuts, in other words.

The trust said in October that 19 per cent of its clients between April and September needed food because of benefit changes and 35 per cent cited delays in benefit payments. Add those two percentages together and you get 54 per cent of cases attributable to either reforms or delayed payments.

We have slightly more up-to-date figures now: between April 2013 and January 2014 17 per cent of food bank users blamed changes in the benefit system and just over 31 per cent blamed benefit delays.

A bigger proportion of people (49 per cent) are blaming their problems on benefits in general now compared to 2012/13 (44 per cent) and to the previous financial year (40 per cent).

One big caveat: these benefit problems include people being “sanctioned” – having their payments cut as a punishment for some misdemeanour. Whether or not that represents a “failure in the benefits system” is of course a matter of opinion.

“5,500 people were admitted to hospital in the UK for malnutrition last year.”

“5,500 people were admitted to hospital in the UK for malnutrition last year.”

Numerically true, but a tricky one to link directly to poverty or benefits cuts.

The latest figures for England from the Health and Social Care Information Centre show 5,499 cases either admitted to hospital for malnutrition or diagnosed with malnutrition after being brought in for something else in 2012/13.

Despite what the Mail says, these figures do not include obesity. But some of these cases could be the same individuals being readmitted more than once in the same year.

That’s a 74 per cent increase over the 2008/09 figure of 3,161.

But the total number of hospital admissions went up by about 7 per cent during that period, and the proportion of elderly people – who may be more likely to suffer from malnutrition – went up too.

We don’t know whether the ageing population is a driving factor here – although interesting to note that there is no evidence of a consistent rise in the number of children hospitalised over the last five years:

As well as trying to allow for demographic trends, we need to be aware that hospitals have increasingly been using a new five-step screening process to identify more cases among patients.

The malnutrition charity BAPEN told us: “The increases in the number of patients at risk of malnutrition is likely to be due to increased awareness of the problem of malnutrition, increased nutritional screening of patients on admission to care and better reporting of malnutrition rather than necessarily just to reduced income and the economic struggle of many families”.

This doesn’t mean acute malnutrition is not on the rise thanks to austerity. In fact, some dieticians are telling us that they think it is. But we need to be cautious about reading too much into the official figures.

Hospital admissions only give us one small angle on the issue. In 2008 BAPEN estimated that more than 3 million people in the UK were either malnourished or at risk of malnutrition, and more than 90 per cent were living in the community.