What if Greece goes bankrupt?

The chairman of eurozone finance ministers, Jean-Claude Juncker, says Greece could go bankrupt if its voters reject the bailout deal in a referendum. Channel 4 News looks at the consequences.

Prime Minister George Papandreou has called a plebiscite on the debt deal he has agreed with the EU and IMF, but it may never be held. First, he has to survive a confidence vote in the Greek parliament on Friday, and with a majority of just two, there is every chance he will lose and have to call an election.

The conservative New Democracy party, which is ahead in the polls, wants to renegotiate the terms of the bailout package, but would find it difficult, if not impossible, to convince Germany and France that the deal agreed days ago should be torn up.

Mr Juncker’s words are designed to put pressure on Greece to accept what was agreed in Brussels, but bankruptcy is possible, whether the country holds a referendum or not.

If the EU and IMF believe Greece is wavering, they could decide to withhold the money they have promised. The banks that have agreed to write off 50 per cent of the money they are owed could also change tack. All of this would leave Greece unable to pay its bills – in other words, bankrupt.

I touch down in Athens with the task of finding what on earth is going on in this country that unwillingly holds the future of Europe in its palm. Generals being fired, all-night cabinet meetings, capital flight and a plausible fall of the government within days.

Read more from Economics Editor Faisal Islam

Disorderly default

If a bailout does not go ahead, with or without a referendum, Greece would default on its debts. If this happened in a disorderly way, a banking crisis would follow, with governments and taxpayers forced to shore them up, as they did in Britain in 2008.

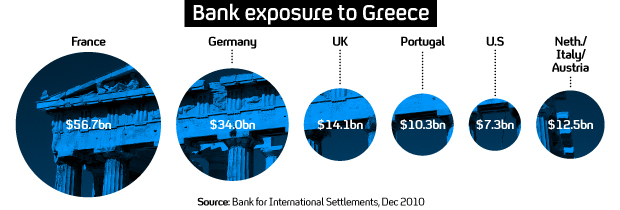

In other words, banks exposed to Greece would have to be recapitalised. Looking at what happened here three years ago, recession could well be the result – at a time many European economies are already struggling.

Dawn Holland, an economist at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, believes Greece’s financial backers – the EU and the IMF – would seek to renegotiate the debt deal rather than allow a disorderly default. “The answer is to try to avoid a disorderly default in Greece that would lead to a banking crisis,” she told Channel 4 News.

York University economist Mike Wickens, who teaches courses at the IMF and advises the House of Lords, thinks Britain would cope bettter than some other European countries if Greece went bankrupt. It would not be a repeat of 2008.

This is because British banks are carrying less Greek debt than institutions in France and Germany, and Britons do not as a rule keep their money in Greek bank accounts.

It does not involve the British household. Prof Mike Wickens, York University

If British banks had been allowed to collapse, customers would have had problems accessing their money,while those with shares in the banks via ISAs or pension funds would have seen their investments wiped out.

Prof Wickens told Channel 4 News: “British households are not as exposed to the Greek banks as they were to British banks early in the crisis. It does not involve the British household and the British government or British banks.

“What is the rational solution? The answer is that individual countries would be willing to bail out their banks just as the UK and Ireland did. If there’s a disorderly default, this is what you’d observe: each individual country will be saving the banks in the same way that Britain did.”

High interest rates

Prof Wickens also believes that those banks that are heavily exposed to Greece have benefited because of the high interest rates they have been charging.

It’s not quite as bad as the banks like to claim. Prof Mike Wickens, York University

“Why have these banks been holding Greek debt? Did governments advise them to do it, or was it because of the high interest rates? What we are seeing is that banks charging high interest rates have already received some compensation.

“It’s not quite as bad as the banks like to claim. It’s not as bad as people claim because the banks have been partly compensated by receiving high interest rates on Greek debt. The same is true for Italy.”

But Prof Wickens said that while Britain could take a Greek bankruptcy in its stride, the possible break-up of the euro would be more serious.

“A cause of concern is the fate of the euro. It’s not the same financial crisis as it was before. Provided that does not happen, I don’t think Britain will be that much affected.”

-

Latest news

-

‘It’s absolutely clear that these advances were unwanted,’ says producer of new Channel 4 Spacey documentary4m

-

India opposition accuses government of ‘crackdown’ as election gets under way2m

-

Sadiq Khan wins historic third term as London mayor2m

-

Labour’s Andy Burnham re-elected as mayor of Greater Manchester4m

-

Andy Street ‘winning or nearly winning’ is an extraordinary result for Tories, deputy foreign minister says4m

-