From City to Sandhurst, a woman’s journey

Heloise Goodley was a high-flying City banker when she decided to quit business lunches for the battlefield. Writing for Channel 4 News she describes her new “way of life”.

Panicked shouting and crackling gunfire shattered the early morning calm as through the darkness pandemonium broke.

Rat-a-tat-tat.

Bawling and hollering the enemy came thundering towards us, crashing through the forest.

Rat-a-tat-tat.

Firing through the trees.

Rat-a-tat-tat.

Just two months earlier I had been a suited and booted civilian, commuting to a desk amidst the shiny glass and chrome of Canary Wharf.

Still wrapped up in my sleeping bag I was startled into consciousness. I tried to dismiss the noises around me for a bad dream, hoping it would go away. I was so tired, all I wanted to do was just sleep and pretend this wasn’t happening.

Rat-a-tat-tat.

Around me the air filled with muffled shouting and smoke. Alice was already awake next to me, galvanised into action, thrusting her sleeping bag into her bergen and tearing down our shelter. She shone the light of her torch at my face, rousing me out of my dream and into the nightmare. “Come on, we’ve got to go,” she urged. Reluctantly I left the relative warmth of my sleeping bag and joined the flustered confusion. We had been living in the forest for four days, sleeping on the cold wet ground beneath the trees. Exhausted, cold, hungry, wet, muddy and bruised I clearly hadn’t thought this through. What error in decisions and failed thought had resulted in me being in this mess?

Just two months earlier I had been a suited and booted civilian, commuting to a desk amidst the shiny glass and chrome of Canary Wharf with the rest of London’s rat race. Now I was sleeping in a muddy hole with a grumbling in my stomach and unwashed hair matted to my head. This was the step change from City to soldier.

Up until now I had managed to go through life in the right order. I worked hard at school, got GCSEs, A-Levels and went to university; where after three years of avoiding serious responsibility I graduated and took a job at a bank in the City that paid well and made my parents proud. I bought sharp suits, wore power heels, sat finance exams and spent two hours of my day at the clemency of London Transport on the underground.

It was utterly soul destroying.

Four years after this highly-paid despair set in I decided I could take it no more and set about looking for Life Plan B, which eventually led me to apply for the army’s prestigious officer training academy at Sandhurst. This took me to the small town of Westbury on the edge of Salisbury Plain, where among the assault course and trout lake the Army Officer Selection Board seek out the enigmatic qualities of leadership that make a British Army officer. It was here, for four days that I was put through my paces, my mental aptitude and physical abilities scrutinised, my political acumen tested and grasp of the English language examined. And here too I experienced my first taste of Army food, abrasive blankets, cold showers and sergeants shouting.

I arrived at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst less than a year later, walking up the steps of Old College along with 270 other new officer cadets. My first days there were spent gripped by the shock of capture amidst a haze of finding my way and uncomfortably wading out of my depth as the umbilical chord was cut and I was delivered into the military. My femininity was stripped away from me as I put on army combats, clumpy boots and scrapped my hair back into a face-liftingly tight bun, while jewellery, perfume and make-up were gravely forbidden reserved for my civilian persona (which wouldn’t be seen for a while).

I clearly remember the moment I was first given my rifle, I held it with great caution, like a new parent with a baby.

I was one of 32 girls who started Sandhurst in the winter of 2007, making up little over 10 per cent of the officer cadets, which is reflective of female numbers in the army as a whole. We were assembled together into what the military call a platoon and comprised a motley collection of University graduates, some school leavers, career changers, ex-soldiers and two foreign cadets (from Nepal and Jamaica).

Our conversion from civilian to soldier was a traumatic one, with a typical day during the initial training starting at the deathly early time of 5.15am – and when I woke my first action of the day was to switch on my iron and iron my bed ready for inspection. The entire platoon of girls would then line up in the corridor outside our rooms in alphabetical order for the daily “water parade”, which involved singing the national anthem and then drinking a litre of water, so that at a completely inopportune moment later in the morning we would all be bursting for the loo.

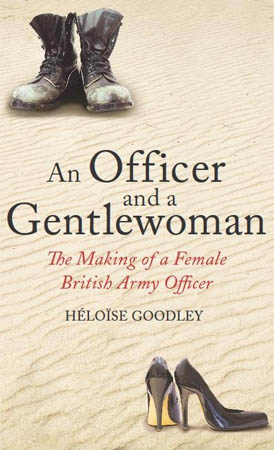

(Pictured: An Office and a Gentlewoman by Heloise Goodley. Published by Constable)

Discipline was harsh and sleep at a premium as our days were filled with parades, marching, room inspections and lessons in military skills such as fieldcraft, map reading, foot care and weapons training, called “skill at arms”. I clearly remember the moment I was first given my rifle, I held it with great caution, like a new parent with a baby, unsure what to make of it. We marched everywhere, even inside, up and down the corridors, and spent lots of time standing to attention, ironing, polishing, cleaning and being shouted at. I learnt to eat five Weetabix in five minutes and reassemble a rifle in under 30 seconds. Slouching was forbidden, no hands in pockets, no leaning against walls, only speaking when spoken to and being late was the most serious of offences. Press-ups were the favoured tool for teaching these lessons and as the weeks passed I got quite good at them.

Life at Sandhurst was harsh but as we deployed out into the field on exercise the comforts of fresh food, running water and sprung mattresses came into perspective. Though outside among nature’s beauty this was nothing like a week of camping in Devon but rather the raw infantry living that the army is based on. We dug holes and hid in them, ran around with guns, ate cold corned beef hash, painted camouflage cream onto our faces and stuck leaves and twigs on our heads in disguise. A lot of time was spent sitting in freezing, wet, muddy puddles wishing I had dry pants on and it was truly horrifying how bad the body could smell following a week of war games in Wales. Sleep on exercise was at even more of a premium than at the academy as we kept sentry watch and patrolled through the night, I once achieved just six hours in four days becoming almost delirious with exhaustion.

It was both the best and worst experience of my life. It changed me. Subtly, not fundamentally.

The regular commissioning course at Sandhurst is eleven months long, split into three terms, Juniors, Inters and Seniors (there are different condensed courses for Territorial Army and professionally-qualified officers; doctors, dentists, lawyers and chaplains – known colloquially as the “vicars & tarts” course).

Located in Old College, Juniors was the Prep School phase, where we sat firmly at the bottom of the pecking order, cowering in the library at break-time as all around us was new and forlorn. Lessons covered the introductory basics as Juniors painfully inducted us into the military, stamping out unofficerly behaviour and civilian tendencies. Then after fourteen weeks in Juniors we metaphorically progressed from shorts to trousers and moved up to the intermediate term and New College with the big kids. In Inters room inspections were replaced by more days in the field as the teaching became more relevant and more real. We learnt practical tactics such as trench and urban warfare, braced the discomforts of chemical combat in gas masks and choked and cried in the dreaded gas chamber – “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”.

By the senior term we were almost the finished article, cold war basics had evolved into Afghanistan scenarios as less time was spent in muddy puddles and more in the lecture theatre and library. Now old hands, we’d learnt all the tricks and were no longer tested on them, sitting comfortably at the top of the pile. Marching was consigned to the parade square and we were finally treated like responsible officers; indeed we’d all soon be in command of soldiers, some even in war zones within only a matter of months.

At the beginning of Seniors we put on our smartest suits, shiniest shoes and bit nails to the bone with nerves as the Regimental Selection Board interviews took place. These decide ultimately where in the Army cadets commission and spend their military careers. For girls the choice of future regimental family is slightly easier as all infantry and cavalry regiments, where their “primary duty is to close with and kill the enemy” are off limits; although over 70 per cent of jobs in the Army are still open and welcome to women. The relation of women to the “frontline” today is a rather blurred one anyway as women serve “outside the wire” alongside their male counterparts, working closely with the infantry on the ground in Afghanistan in positions of considerable risk. Women work in the army as medics, intelligence officers, interpreters, dog handlers, military police, artillery forward observation officers, interpreters and many other roles.

The commissioning course finally culminates in a day of great pride, pomp and ceremony as parents and dignitaries gather in seating stands erected along side the parade square for the Sovereign’s Parade. Before them 500 cadets march to a military brass band puffed with nervous pride and a stiffener of port in a display of sword flashes and rifle clashes. Later that night as the clock struck midnight, under the crackle and pop of fireworks and champagne corks we officially commissioned as young officers and were cast forth to face our biggest challenge yet; soldiers.

It wasn’t until I had commissioned, and entered the real army, beyond the gilded gates of the Academy that with acquired knowledge and hindsight I could look back and say I had actually enjoyed my time at Sandhurst. It was both the best and worst experience of my life. It changed me. Subtly, not fundamentally. I’m still the same person, with the same manners and methods. But the experience improved the basic template of me. The challenge and reward were hugely gratifying and I achieved physical and mental heights far beyond that my self-evaluating brain would allow. For me the army fits. In it I have found more than a job I love, but also a way of life. A way of life I am happy to be part of. In the forces I am now a member of a close-knit community in a way that employment in my London job never could be. The army is more than just nine to five and a pay cheque at the end of each month. It defines who I am and I’m proud to be part of it.

An Officer and a Gentlewoman: the Making of a Female British Army Officer by Heloise Goodley is published by Constable & Robinson.

-

Latest news

-

‘Government responsiveness should be improved’ says infected blood inquiry chair4m

-

Infected Blood scandal: How UK failed on a global scale4m

-

‘There’s a strong evidential basis’ for ICC to grant arrest warrants for Netanyahu, says criminal law expert4m

-

International Criminal Court prosecutor seeks arrest warrants for Israel PM and Hamas leaders3m

-

‘Highly unlikely there was foul play’ in Iran president helicopter crash, says Tehran professor5m

-