Iran: revolution revisited

Against a backdrop of growing diplomatic tensions, the nuclear question and increasing reports of human rights abuse, Iran marked the 31st anniversary of the 1979 Islamic revolution in February 2010.

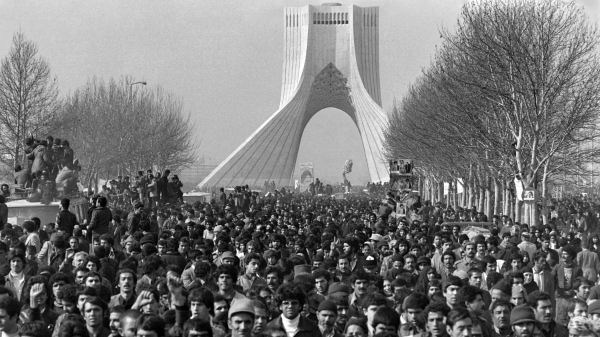

Thirty-one years after huge crowds ushered in an Islamic republic following the overthrow of the monarchy, thousands rallied for the official anniversary celebrations in Tehran’s Azadi Square, known as Freedom Square, but with a distinct mood of discontent growing on the fringes.

To the north opposition supporters gathered in Saddeqiya square where opposition leader Mehdi Karroubi was attacked as he tried to join the crowd.

Heavy security prevented the planned large opposition gatherings in Enqelab and Haft-e-Tir squares. But a small group of protesters did manage to protest outside Evin prison where many political detainees are being held.

The anniversary of the 1979 Islamic revolution fell at a time when Iran had begun to witness the first unrest since those historic days 31 years ago.

During his address, President Ahmadinejad announced that Iran was capable of enriching uranium to more than 80 per cent purity, coming close to levels experts say would be needed for a nuclear bomb, although he said that was not the country’s intention.

The anniversary of the 1979 Islamic revolution fell at a time when Iran had begun to witness the first unrest since those historic days 31 years ago.

The disputed election of June 2009 exposed deep divisions in the establishment. Authorities denied allegations of vote-rigging.

Jon Snow recalls ‘a moment in modern history'

I was there! Thirty-one years ago, wedged amongst a chanting, seething sea of black-clad women in chadors moving through downtown Tehran. So dense was the throng that even filming what we were witnessing proved almost impossible.

It was exciting, we knew the Islamic revolution - a people's clamour for change, for spiritual renewal in the aftermath of the feeble fading of the Shah's corrupt pro-Western regime - would change the balance of the world in which we lived, but we could not fathom how.

We knew too that we were "in on a moment of modern history".

Read more

The same mistakes, 31 years later? Iran expert Massoumeh Torfeh writes for Channel 4 News:

Over 55 journalists are in jail in Iran – the highest on the list of the Committee for the Protection of Journalists.

In total, over 3000 people are said to be in prisons since the contested presidential elections. Many are young men and women, students, intellectuals, academics, and writers.

They have gone through show trials, made seemingly false confessions and are now behind bars for an average of eight years.

Two young men were executed last week and another has received his verdict. Eight more are on the line. They are described as Mohareb (enemy of God) invariably accused of spying for the west – especially the UK and the US.

The introduction to their indictment refers directly to the Brookings Institute that had “written articles discussing soft revolution and popular uprising” as being the preferred American path in Iran.

How and on what basis these young men were connected to those articles was not made clear. Nevertheless they were killed.

It is 31 years since the Shah of Iran was ousted by making a similar set of mistakes. First he ignored the real grievances of the population, and then he continued with his belief that he was the “king of kings” and the sole representative of 2500 years of monarchy in Iran.

He alienated the masses by monopolising power and by consulting only a small circle of loyalists – just as the hard line clergy are doing today. And then once matters got out of hand, in desperation, he accused the West of having engineered the revolution through the BBC Persian broadcasts.

“It is 31 years since the Shah of Iran was ousted by making a similar set of mistakes”

He called the BBC his “enemy number one” just as the Islamic Republic is accusing the BBC Persian TV of “soft power war”. However, at least the Shah admitted towards the end that he had “heard the voice of the revolution”.

Dictatorships always find an excuse for legitimizing their illegitimate rule. And then when they are hit back by the thrust of popular anger they seem to find it difficult to believe.

For over a century – 104 years to be precise, since the Constitutional Revolution of 1906 – people of Iran have been demanding freedom and justice. Yet rulers have deceived them time and again as we have seen in three major movements for democratization in Iran.

Authoritarian regimes were reinstated, every time more brutal and more organized than before. These appear to be fresh in the memory of the young generation.

YouTube and social networking sites favoured by young Iranians are these days full of references to those movements.

There are photos of the Constitutional Revolution showing men chained by the Qajar dynasty. Young artists are reviving poems that originated then yearning for freedom. The popular group Kiosk, until recently an underground group in Tehran, has just put out a joint production with the pop singer Mohsen Namjoo based on one the most loved songs of the constitutional era – Morgh e Sahar (the early morning bird).

The lyrics written by the constitutional era poet, Bahar, express a yearning for the end of the dark night, and the breaking of the dawn which would bring with it the breaking of the chains of prison when the early morning bird would sing the song of freedom for all.

Another song, Shame on You, based on a poem by Fereydoon Moshiri in 1953 expresses the pain of mothers whose children are in prison. It condemns the “gods of power” for being oblivious to what is going on around them.

“This time the same question is posed over the future role of Islam in the political structure of Iran”

The revival of these songs by the young carries a message for the authorities and a tacit warning.

The crisis in Iran is no longer over who should be the president. It is not even about the role of the Supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, for that may be a foregone conclusion.

The crisis for the Shah was over the role of monarchy since in the collective psychology of the people the monarchy had gone further than its mandate. And this time the same question is posed over the future role of Islam in the political structure of Iran.

That may be the “voice of the revolution” that the supreme leader would have no choice but to hear sooner or later.

Massoumeh Torfeh is a research associate at SOAS specialising on the politics of Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia. She is a former BBC journalist and UN spokesperson.

-

Latest news

-

What do Tory heartland voters want? A view from East Sussex4m

-

IDF ‘tactical pause’ to allow Gaza aid criticised by Israel leader Netanyahu3m

-

Social media ‘part of the problem’ in undermining politician security, says former MP5m

-

Conservatives and Labour under pressure to explain NHS plans3m

-

Euro 2024 shooting: man with axe shot by Hamburg police3m

-