The government has announced a £1.3bn plan to expand the mental health workforce with a “challenging” recruitment drive.

The aim is to help the NHS care for an additional one million patients by 2020-21, according to the health secretary, Jeremy Hunt.

We put his claims to the FactCheck test.

Are nurse numbers really on the rise?

Speaking to the BBC about the mental health plans, Hunt invited people to “look at our track record”.

He claimed: “We do have 6,000 more people in nursing … The actual numbers of people working in the health service are going up.”

At first glance, the latest NHS figures appear to support the gist of this claim.

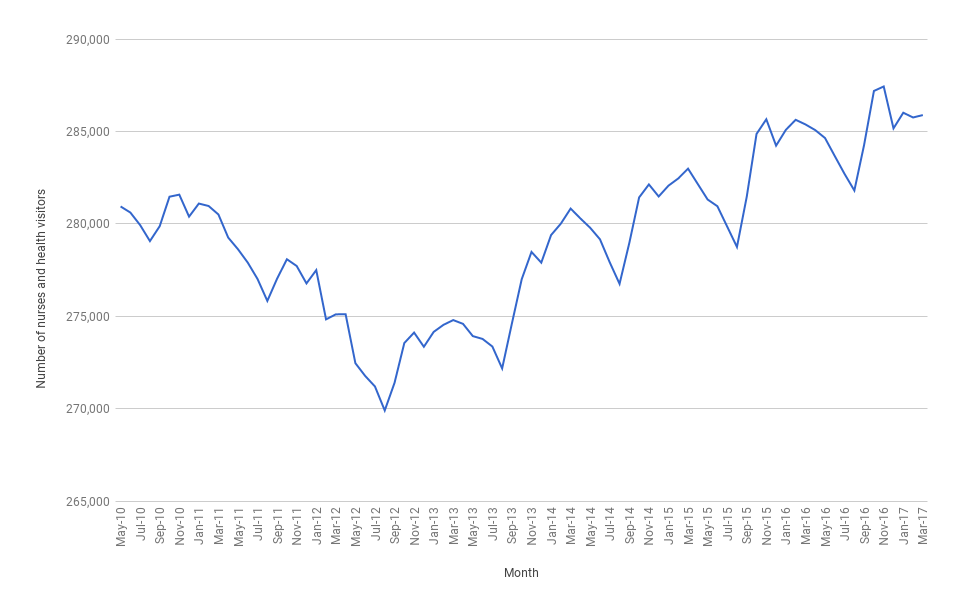

When the Conservatives came to office in May 2010, there were 280,950 nurses and health visitors in the NHS, overall. That number had risen to 285,893 by March this year.

That’s around 5,000 more nurses – not the 6,000 Hunt claimed, but an increase nonetheless.

However, Hunt’s announcement was about mental health recruitment, and these figures cover all aspects of the NHS. Only a small proportion of these nurses work in mental health.

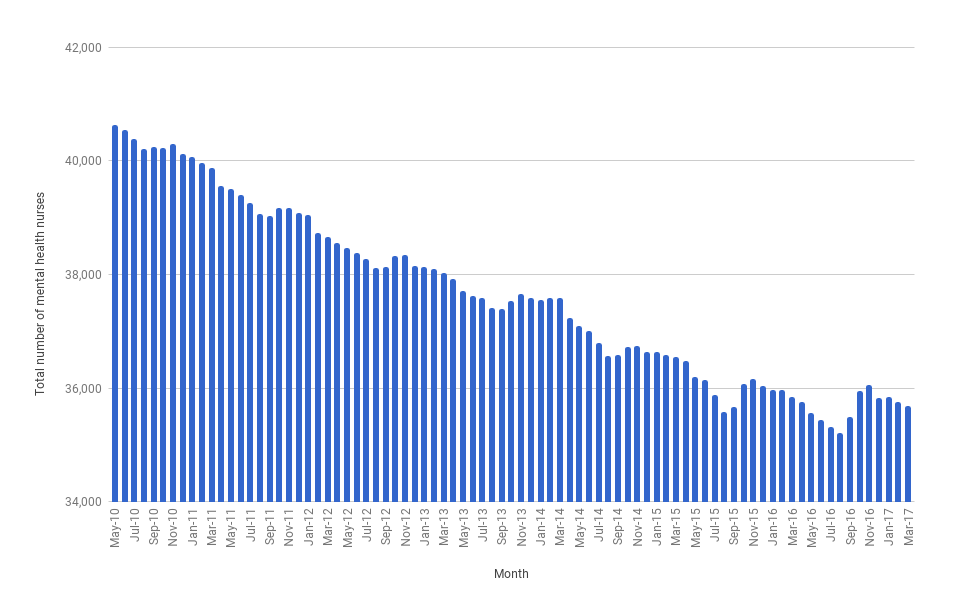

If we look specifically at mental health nurses, the number has actually gone down. The workforce has been reduced by 12 per cent since May 2010.

It is also worth bearing in mind that these figures only represent the number of nurses, rather than the nurse-to-patient ratio.

While we don’t have figures for every patient who sees a nurse, there is evidence that mental health nurses in NHS hospitals are seeing their caseloads rise.

Admissions rose by an estimated 8,853 (7.5 per cent) between 2011/12 and 2015/16 and bed days went up by 4,532 (22 per cent).

Are enough nurses being trained?

Speaking to Channel 4 News, Hunt said: “In the case of mental health nursing, we have 8,000 nurses in training at the moment. If we can get them all to work in mental health, that would be a 22 per cent increase.”

We’re not certain how this figure for the number of nurses in training has been calculated. The Department for Health told us that the number of nurses in training was provided to them by Health Education England (HEE). HEE has not responded to our request for confirmation yet, but we will update this when they do.

However, even if this figure is right, there are a number of major flaws with Hunt’s logic.

First of all, Hunt assumes that all mental health nursing students will immediately get jobs as mental health nurses in the NHS. But this sounds like wishful thinking.

Even the universities that advertise training don’t claim that absolutely all of their students get jobs within six months of leaving. Some may go on to further study, switch to a different type of nursing, work in the private sector, or even get an entirely different job.

The health secretary might reasonably rely on most of these students getting jobs as mental health nurses pretty quickly. But the idea that 100 per cent of them will also seems unrealistic.

Secondly – and more significantly – it assumes that no one who currently works as a mental health nurse will leave, retire, or switch jobs. Again, this would obviously not be the case.

Indeed, the HEE has warned about staff retention issues in nursing, saying that “there needs to be increased retention of new graduates and

current staff”.

A report said the NHS should “make improving retention and staff engagement a key strategy”.

It added: “It is less expensive to retain the nurses than to recruit, train and place new ones. Many healthcare providers struggle to fill nursing vacancies and need to develop robust nurse retention strategies to prevent further nurses leaving … Retention strategies are likely to be significantly cheaper than recruitment strategies.”

Hunt’s optimism assumes that the flow of new trainees will continue in future years.

But there has actually been a slump in applications to study nursing and midwifery: they dropped by 23% after the government scrapped NHS bursaries.