Government ministers consistently hail the UK’s coronavirus vaccine programme as a massive success.

The rollout of vaccines developed by the drug companies AstraZeneca, Pfizer and Moderna has certainly helped save many lives, and could be the reason why infection rates appear to be slowing.

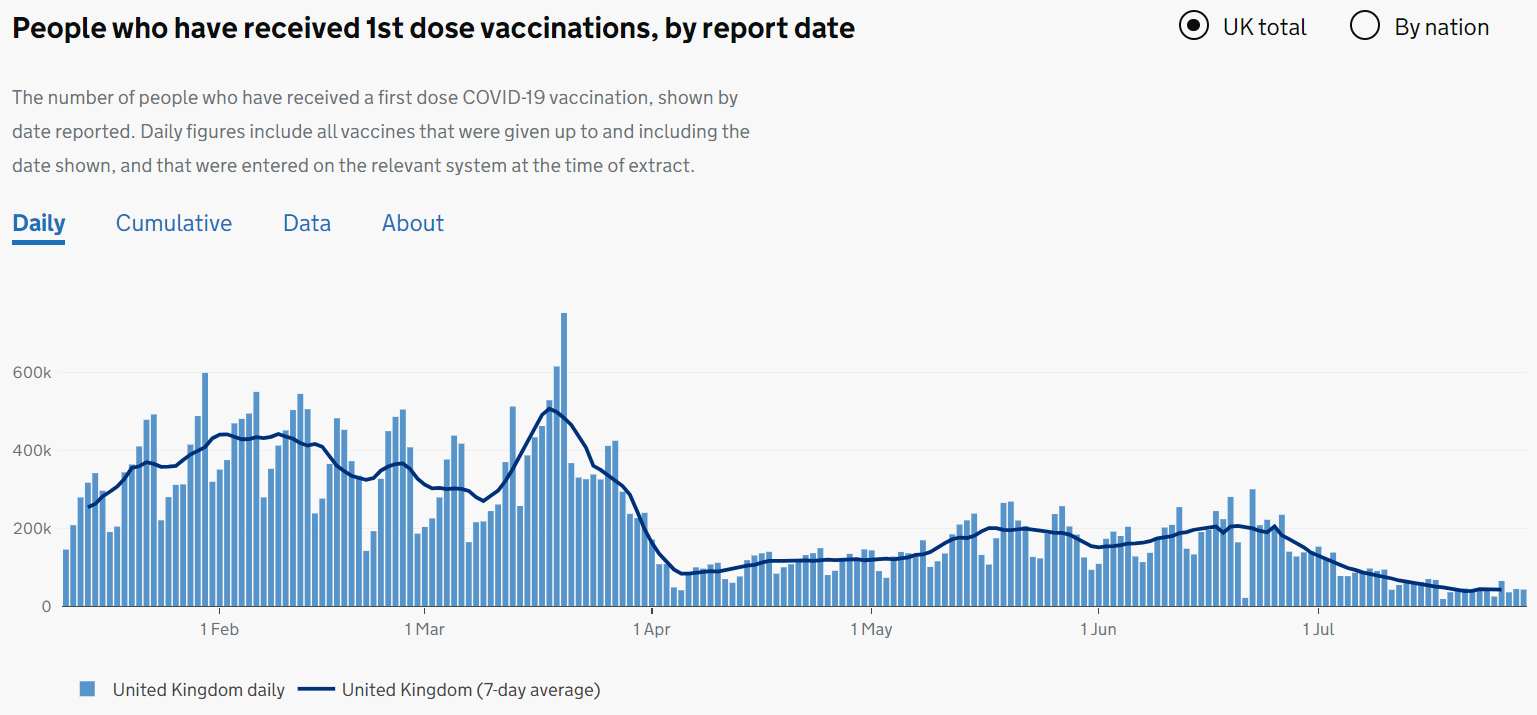

But the number of daily vaccinations has fallen recently, with some of the lowest numbers of daily jabs occurring this month. What is going on?

Big falls

The number of daily vaccinations fell dramatically in late March and April, when we went from a high of 750,000 first doses administered in one day to fewer than 50,000.

The problem then was supply. Imports of AstraZeneca vaccine made by the Serum Institute of India were initially delayed, then the Indian government banned exports of the vaccine.

Britain’s vaccination programme never regained the heights seen in February and March, but daily totals did increase until the end of June. The average number of jabs done each day has been steadily falling for about the last month.

Supply or demand?

The UK government told FactCheck there is no issue with supply, as you would hope given that all adults were offered a first dose of vaccine last week.

A spokesman said: “There are no shortages of vaccines. We are doing everything we can to boost uptake for younger people and urge all those who have yet to book their appointment to do so as quickly as possible to help protect themselves and their loved ones.”

Independent scientists who advise the government as part of the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) have said in recent weeks that they are not aware of any constraints on vaccine supply.

This suggests that it is simply taking longer to reach the last adults in the country who have not yet taken up the offer of a vaccine – those aged under 30, and the small numbers of people in older age groups who have so far declined.

It’s not clear what is behind the reluctance among some people to get jabbed, but one slightly concerning trend in the data is that the younger the age category, the bigger the proportion of non-vaccinated people.

For example, the figures for England on the UK Coronavirus Dashboard show that in the oldest band, the over-90s, 94 per cent of people in have had a first vaccination (alternative figures published by NHS England are higher).

That number drops to 86 per cent for people aged 50-54, and it has been stalled around that mark for the last month.

There appears to be a natural ceiling for the level of demand, and the percentage falls as you go down the age groups. At time of writing, only 60 per cent of the youngest adults, aged 18 to 24, have received a jab, although that number is still climbing. It remains to be seen at what point demand will level off in this age group.

The government says it is working hard to encourage uptake among younger age groups including partnering with celebrities, social media platforms and dating apps to get the message across about the benefits of vaccines.

AstraZeneca advice changed

Although there is no evidence of a supply problem, it’s clear that we are currently relying heavily on Pfizer vaccine to cover the remaining adults in the country.

Figures published by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) regulator show that we effectively stopped using the AstraZeneca vaccine for first doses several weeks ago.

This follows advice from the JCVI that under-40s should be given an alternative vaccine where available.

It came after widely publicised reports of extremely rare occurrences of blood clots combined with low platelet cell counts among people who had recently had a first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine, although recent evidence is emerging which suggests the danger of this condition may have been overblown.

A new preprint (not peer-reviewed) article published in the Lancet this week looked at more than 1 million patients in Spain and found that both the Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines were similarly associated with a slightly higher risk of blood clots in the veins, although getting ill with Covid-19 was much more likely to cause clots.

The blood clot with low platelet condition was no more likely to occur in people who had received either vaccine than would be expected in the general population.

The verdict

Figures from the medicines regulator suggest that Britain has effectively stopped using AstraZeneca vaccine for first doses, after scientists recommended that younger people be given an alternative.

But the UK government says supply is not the reason why vaccination rates have slowed.

The stats in England suggest that the younger you are, the more likely you are to skip vaccination – although the NHS is still trying to reach everyone.

The government says it is working to encourage uptake among younger adults, and the UK has some of the highest vaccination rates in the world.