Oxford University published its latest admission statistics this week.

In a country where seven out the last 10 Prime Ministers went to Oxford, the question of who gets to attend our elite universities is obviously massively important.

The headline figure showed that 1.9 per cent of UK students admitted to Oxford in 2017 were black. Black people made up around 3 per cent of the UK population in 2011, according to the latest census.

The former Labour higher education minister David Lammy called the university a “bastion of entrenched wealthy, upper-class, white, southern privilege” and called for “systemic change” in reference to his analysis of Oxford’s own college-level data released this week.

His analysis of that data is largely correct and there is a smaller percentage of black people at Oxford than there are in the country.

He also says that Oxford is putting too much blame on schools and application rates – so how is entrenched inequality affecting the selection process?

Oxford denies any discrimination in its selection process but has announced an increase in places on spring and summer schools designed to encourage more applications from under-privileged schoolchildren.

Oxford’s director of undergraduate admissions, Samina Khan, said: “We are not getting the right number of black people with the talent to apply to us and that is why we are pushing very hard on our outreach activity.”

FactCheck looked at this issue last year, finding that both the number of black applicants to Oxbridge is low and that very few black British students are making it to Oxford and Cambridge.

We also found that black students are more likely to miss predicted grades – so it may not be Oxford that’s entirely to blame, but the education system itself and deeper socioeconomic factors.

Some have argued an immediate solution would be to try better to reach a larger pool of potential candidates by encouraging talented pupils to apply from under-represented races, regions and economic backgrounds, in particular from state schools.

So let’s check out the latest stats and see if we can figure out what’s going on at Oxford by looking at a wider range of data than was released this week.

How many black pupils apply?

Oxford can only deal with pupils who apply in the first place. In 2017, 396 UK-domiciled black people (including African, Caribbean and “other”) applied for an undergraduate place at the university out of 12,583.

You can check out the detailed admissions stats here.

That’s about 3 per cent of all applications – roughly in line with the percentage of black people who live in the UK.

But as a raw number, it’s very small. And then Oxford only offers places to a fraction of those applicants – 65 people in 2017.

And then only some of those students who get offers will only take up a place. Last year the number was just 48.

So low admissions means the final number of black students who actually attend Oxford is always likely to be very small, even if you leave aside any question of bias or prejudice.

Scatter these black students among the the 30-odd Oxford colleges that take undergraduates, and it becomes easier to see why colleges might have tiny numbers – or even none at all in some years – without this necessarily being evidence of racism.

The minimal increase in state school intake to Oxford over the last five years appears to show that slow progress is being made.

Better outreach at state schools could widen the pool of potential candidates for Oxford and Cambridge places, which is small from the outset.

So how many black students get offers?

This is the bit the university has the most control over, and it’s where we would expect to find evidence of systemic bias.

On the face of it, black students do appear to get a raw deal at the offers stage: only about 16 per cent of black applicants receive an offer, compared to 26 per cent of white applicants.

But there’s a complicating factor…

Black students are choosing the most competitive courses

You’re less likely to get an offer if you apply for an over-subscribed subject, where competition for places is higher. And black students are much more likely to apply for the most popular courses than for niche subjects with less competition.

Oxford says that between 2015 and 2017, 41 per cent of applications from black pupils were for Medicine and Law, compared to about 12 per cent for white students.

To understand whether there’s evidence black students are being discriminated against, you need to allow for the courses people apply for.

And you need to allow for their predicted grades, to make sure we are making a fair comparison between pupils of similar academic attainment.

Oxford was very slightly more likely to offer a place to black candidates in 2017, once you allow for course and grades

This wasn’t true last year, but it was also true the year before. What’s going on?

Ucas is the agency that runs the university applications process.

Its analysis shows that a black applicant to Oxford is very slightly more (0.5 per cent) likely to receive an offer than the average applicant who applies for the same course and has the same predicted grades.

(Here – page 12 shows that 2017 data. In some years it’s slightly above average, in others slightly below. The technical notes to the data make clear that these statistics do take into account predicted grades, an assertion which David Lammy has questioned.)

But if black pupils were slightly more likely to get offers this year, why do they remain under-represented at the university?

Black students are more likely to miss their grades

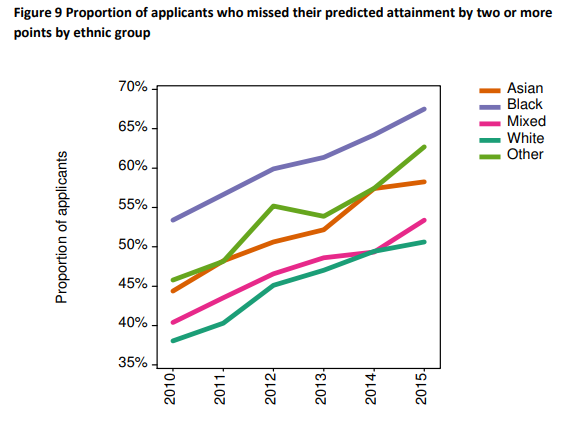

Ucas has also noted a long-term trend of black pupils being more likely than others to miss their predicted A-level grades:

This may explain why, from 2015 to 2017, black applicants to Oxford were less likely than people from other ethnic groups to take up a place after getting an offer.

We can’t say for sure that missing grades is the biggest factor here, but common sense suggests that people who apply to Oxford want to go there, and tend to take up places if they can.

Factor actual achievement at A-level into the equation, and there’s less evidence of inequality at Oxford.

In 2017 1.9 per cent of Oxford students were black. A similar proportion of UK pupils who got three As at A-level were black in the latest year we know about (1.8 per cent in 2015).

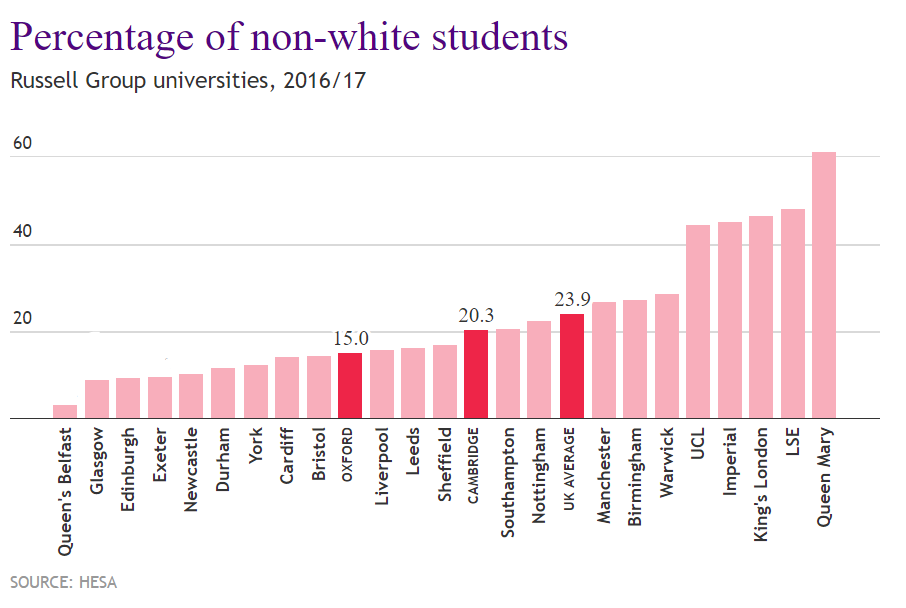

Oxford is not the whitest university

Readers who have been taking an interest in this story on social media have asked us how Oxford compares to other UK universities for racial diversity.

Unfortunately the latest stats are for 2016, not 2017, and there are slight differences in the numbers put out by Oxford that we haven’t been able to get to the bottom of.

But the HESA figures cover the whole UK higher education sector, and make for interesting reading.

Oxford is certainly down at the lower end of the scale, with 1.2 per cent black students in 2016, when the UK average was 7.2 per cent.

Three members of the 24-strong Russell Group of elite universities had a smaller proportion of black undergraduates: Queens in Belfast, Edinburgh and Glasgow.

But if you include all ethnic minority students, nine Russell Group universities have fewer non-white students than Oxford. (And it’s interesting to note that Cambridge is fairly close to the national average.)

The bigger picture

There’s no dispute about the fact that Oxford has a disproportionately low number of black students, although as we have seen, the causes of these may be more complex than they first appear.

As we pointed out in a previous FactCheck article, black pupils tend to under-perform at A-level compared to other ethnic groups. Academics have variously blamed this on poor teaching, economic deprivation, housing, lack of support from parents and a host of other factors.

There are other apparent inequalities in the admissions numbers too. Just under 42 per cent of undergraduates admitted to the university in 2017 went to private schools. Nationally, only around 7 per cent of children attend private schools.

Oxford has acknowledged that it needs to more to increase diversity, and has just announced that it will offer more places on spring and summer schools designed to encourage applications from pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds.

[This article was expanded and updated on 26 May to add more context. The headline was edited.]