A Telegraph article offering an optimistic vision of life outside Europe has thrust Boris Johnson back into the political limelight.

Is the Foreign Secretary and leading Leaver considering a run for the Tory leadership? Should Theresa May sack him? Did he make a tactical error in reviving the controversial claim that Britain pays £350m a week to the EU?

We can’t answer all of these questions, but we can see how Johnson has changed his position on some of the key Brexit issues.

What’s the new £350m a week claim?

Here’s what Boris actually said in the article (it’s on the Telegraph website behind a paywall, but reproduced in full on his Facebook page).

“And yes – once we have settled our accounts, we will take back control of roughly £350 million per week. It would be a fine thing, as many of us have pointed out, if a lot of that money went on the NHS, provided we use that cash injection to modernise and make the most of new technology.”

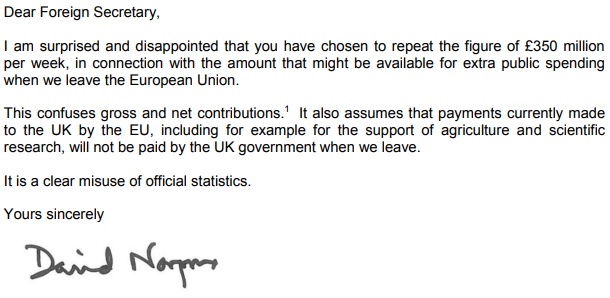

This paragraph led to a slap-on-the-wrist letter from the UK Statistics Authority Chair Sir David Norgrove…

… to which Johnson quickly responded (here).

The back story is that Leave campaigners – starting with Ukip, years before the EU referendum campaign – have always sought to use the highest possible figure when discussing Britain’s contribution to the EU budget.

They tend to focus on a gross figure, rather than a net figure – which takes into account the rebate Britain negotiated in the 1980s, and ways in which EU money paid into Brussels eventually flows back to the UK.

We’ve FactChecked this to death in the past and the full detail is here. Suffice to say that Britain does not in fact spend anything like £350m a week on EU membership fees.

Vote Leave was told this repeatedly by the UK stats watchdog, the Treasury Select Committee, think-tanks like the Institute for Fiscal Studies and independent fact-checkers like us, but chose to put the number at the heart of the referendum campaign.

Was Boris right?

If we go back to the precise wording of the Telegraph article, we can see that the Foreign Secretary chooses his words fairly carefully.

He talks about “taking back control” of the gross EU budget contribution rather than having all that money to spend, and he doesn’t pledge all of that sum for the NHS.

It’s fair to say that this process of sending money to the EU, then getting some of it back, does involve some loss of control over how the money is spent.

For example, Britain has to bid for money to fund research under the Horizon 2020, and EU institutions ultimately decide who gets the money.

On the other hand, events have shown that the government is reluctant to change the existing spending plans. One of the first things ministers did after the referendum was to promise match EU funding streams until 2020.

It’s harder to argue for a significant loss of control over the rebate money. The EU just applies the discount to Britain’s EU budget contribution, without dictating how it should be spent, although the money is paid a year in arrears.

Has he changed his tune?

It’s worth pointing out that Boris hasn’t always chosen his words as carefully when discussing the £350m.

Now we “take back control” of the money and will be able to spend some of it on the NHS.

Compare this to the speech he made in this ITV referendum debate in June last year.

He urged voters to: “Take back control of huge sums of money – £350m a week – and spend it on our priorities such as the NHS.”

It’s the “spend it” bit that’s the problem here: there is no £350m to spend, as Boris now admits.

He was also photographed next to a Vote Leave campaign poster which read: “Let’s give our NHS the £350 million the EU takes every week.” Same problem.

What’s the bigger picture?

Of course, seeing Britain’s exit from the EU as some kind of windfall only works if it doesn’t hurt the public finances more generally, cancelling out any money we would save from membership fees.

In a paper they put out just before the referendum, the IFS put Britain’s likely future annual membership fee at around £8bn, pointing out that this saving would be wiped out completely if GDP was 0.6 per cent lower than it would have been otherwise.

Most serious economic analyses thought the real cost of Brexit would be more like 2 or 3 per cent of GDP, but of course there is a huge amount of uncertainty around all such predictions.

In his article, Boris plays down the short-term effects of Brexit, pointing out that one negative prediction of 500,000 job losses has failed to materialise.

He didn’t mention other ways in which many experts believe Britain has already suffered economically since the Leave vote, which FactCheck looks at here.