“I spent my career as a senator and as vice president working to pass commonsense gun laws. We can’t and won’t prevent every tragedy. But we know they work and have a positive impact.”

That’s what President Joe Biden said in his address to the nation following the news that a gunman had killed 19 children and two teachers at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas.

But the state’s own governor, Greg Abbott – who told the National Rifle Association after the 2018 Santa Fe school massacre in which ten people died that “the problem is not guns, it’s hearts without God” – said in response to the latest shooting that more firearm restrictions are “not a real solution”.

So does gun control work? Let’s take a look at what we know.

States with strictest laws have lowest gun death rates

Exactly who’s allowed to buy and use what type of weapon and under what circumstances varies from state to state – which can make comparing the overall stringency of different states’ arrangements tricky.

No metric is perfect, but we’re using the Gun Friendly Index, compiled by pro-gun legal organisation, AZ Defenders, which looks at a range of firearms laws in each state. These include whether and how long you have to wait between buying a gun and being able to take it home, the extent of background checks you have to undergo, and whether you’re allowed to openly carry firearms in public.

Using this information, combined with their subjective assessment of “strength of gun culture”, AZ Defenders gives every state a score. A low mark means the state is “less friendly” to gun owners, while a high score means the state is “more friendly”.

We compared these scores with US Center for Disease Control (CDC) data on firearms deaths in 2020 – including homicides, suicides and accidents.

More than 45,000 people died from gun-related injuries that year. Some 54 per cent of the deaths were by suicide.

Our analysis found that states with looser gun rules tend to suffer higher rates of firearm-related deaths per 100,000 people, while those with the toughest regimes saw the lowest death rates.

We calculate that the “correlation coefficient” between these two measures is just over 0.7. That means that a 10 per cent increase in a state’s Gun Friendly Index score is associated with a 7 per cent increase in the firearms death rate, on average. This is normally considered by statisticians to be a strong correlation.

Each dot on the graph below represents one of the fifty states. The relationship is clearest in those clustered in the bottom left of the graph. The seven states where it’s hardest to get and legally use a gun (including New York, California, Massachusetts and Hawaii) were also the seven states with the lowest firearm death rates.

But as regular FactCheck readers will know: correlation does not equal causation. Just because we can draw a line on a graph doesn’t mean we know that it’s gun laws driving the difference.

So let’s see if we can go further: can we establish whether any particular policies affect gun deaths?

Background checks on private sales

After a tragedy like the one that hit Texas in May, we often hear politicians and commentators call for tougher or more broadly applied background checks – where a person has to pass criminal and mental health records checks before buying a gun.

Current federal (i.e. national) law says licensed firearm dealers must carry out background checks on anyone attempting to buy a gun. Democrats in Congress want to expand this to cover private sales – trades between individuals or at gun shows – across all 50 states. Their Republican opponents have consistently blocked the legislation.

A major analysis of thousands of scientific papers carried out by the nonprofit think tank, the Rand Corporation, found “moderate” evidence that the current federally mandated background checks by licensed dealers reduce homicides.

“Moderate” here means: “Two or more studies – at least one of which was not compromised by serious methodological weaknesses – found significant effects in the same direction, and contradictory evidence was not found in other studies with equivalent or stronger methods.”

But they said the evidence was “inconclusive” that background checks for private sales – which currently operate in some states – reduce murder rates.

“Inconclusive” means that studies of similar quality pointed in different directions, or that just one study could be found and it only yielded “uncertain or suggestive” results.

And it would seem that background checks did not stop the Texas elementary school attacker from buying his two assault rifles and 375 rounds of ammunition – which he did legally from a licensed dealer just days after his eighteenth birthday. This isn’t surprising as, according to Governor Abbott, the suspect had no criminal record and no known mental health history and so would not have been flagged by a standard background check.

Expanding domestic violence background checks

On average, 70 American women are shot and killed by an intimate partner every month, according to Everytown, an organisation that campaigns for tougher gun laws. Another activist group, Giffords, puts the figure at 600 a year, or 50 a month.

As it stands, federal law prevents someone buying a firearm from a licensed dealer if they’ve been convicted of domestic violence misdemeanours, or are subject to some types of domestic violence restraining order.

But there are gaps in the types of restraining orders that are covered at the federal level. And the Rand analysis finds “moderate” evidence that when states fill in those gaps – blocking more abusers from access to guns – the rate of intimate partner homicides goes down.

What about the link between domestic violence and mass shootings? Giffords says: “In more than half of mass shootings where four or more people were killed, the shooter killed an intimate partner, and one analysis found that nearly a third of mass shooters had a history of domestic violence”.

The analysis in question found 28 out of 89 mass shooters over the period 2014 to 2017 were “suspected” of domestic violence (that’s about a third). Of those 28, the researchers found 17 had “been involved with the justice system for domestic violence”, including six who’d been convicted.

But the Rand Corporation, which looked at thousands of research papers published over several decades, found no studies on the relationship between domestic violence restrictions and mass shootings that even met the threshold for inclusion in its analysis.

Banning assault rifles

En route to the funeral of a victim of another recent shooting in Buffalo, New York, vice president Kamala Harris said on Sunday: “We know what works on this, it includes let’s have an assault weapon ban”.

As in Ulvade, Texas, the alleged Buffalo shooter – who has been charged with the murder of 10 people in a supermarket in a racially-motivated attack – purchased an assault rifle legally aged 18.

There’s no single definition of an assault weapon – and some pro-gun groups even consider the term controversial – but in 1994, the US Department of Justice described them as “semiautomatic firearms with a large magazine of ammunition that were designed and configured for rapid fire and combat use”.

That same year, the Clinton administration banned the making, transfer or possession of semiautomatic weapons nationwide. But the legislation had a built-in expiry date of September 2004, at which point Clinton’s successor George W Bush declined to renew the regulations.

This presented what scientists sometimes call a natural experiment. Comparing the times before, during and after the ban could shed light on whether restricting access to assault weapons meaningfully reduces gun deaths.

Here’s a graphic from the Financial Times. Looking at the time before 1994 and after 2004, it suggests that mass shootings were less common and less deadly during the federal assault weapons ban than in the periods before or after it was in place.

A 2019 peer-reviewed study published in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery reaches a similar conclusion: “Mass-shooting related homicides in the United States were reduced during the years of the federal assault weapons ban of 1994 to 2004”.

But as those authors point out, the research is “observational” – meaning it can’t tell us whether it’s the assault weapons ban that caused the reduction in shootings and deaths.

The Rand Corporation’s assessment of studies that aim to work out if there’s a causal link between the two found “inconclusive” evidence when it comes to mass shootings and other homicides.

And we should also say that while assault weapons seem to make it easier to kill large numbers of people in a short space of time, they are only involved in 16 per cent of mass shootings – according to research by Everytown. The group estimates handguns were involved in 81 per cent of mass shootings, and were the only type of weapon used in 60 per cent.

Clearer evidence for other policies

We have stronger causal evidence that removing “stand-your-ground” laws – which currently operate in 34 states – saves lives. Here’s how the Rand Corporation explains this type of law: “Self-defense has long been available as a criminal defense for fatal and nonfatal confrontations. Traditionally, this defense imposes a duty to retreat before using force, if safe retreat is available. Stand-your-ground laws – referred to by some as shoot-first laws – remove this duty to retreat in some cases of self-defense.”

The Rand analysis finds “supportive” evidence that stand-your-ground laws increase firearms homicides. This is the most powerful ranking the analysts award and means that three or more high-quality studies found the policy had “suggestive or significant effects in the same direction using at least two independent data sets”.

And as the Washington Post notes: “The higher rates [of gun deaths] aren’t simply from ‘bad guys’ getting shot; the research [as analysed by the Rand Corporation] shows the additional deaths created by stand-your-ground laws far surpass the documented cases of defensive gun use in the United States.” In other words, the research suggests people are more likely to commit murder – not just kill an attacker in self-defence – if they live in a state that provides a strong legal protection for the person who shoots first.

Child-access prevention laws seem to save lives too.

They “allow prosecutors to bring charges against adults who intentionally or carelessly allow children to have unsupervised access to firearms” says Rand. Its analysis found “supportive” evidence that such policies reduce suicide and accidental deaths.

Why don’t we know more?

It might be surprising to learn that a topic of such significance – and one that attracts so many academic researchers – is relatively light on definitive evidence.

Shouldn’t it be clear by now whether or not high-profile measures like banning assault weapons or expanding background checks actually lead to fewer deaths?

But we have to remember that gun deaths and gun policies do not exist in a vacuum. There are thousands of potential confounding variables – like poverty, attitudes to firearms, the overall prevalence and nature of violence, the ease with which people can acquire weapons illegally – that can all interfere with our ability to isolate the cause of gun deaths in a state or city.

And it’s even been suggested that some academic studies that appear to investigate the effect of gun control measures are destined from the outset to “find nothing”. That’s the claim of one Harvard professor – David Hemenway, head of the university’s Injury Control Research Center – who analysed two papers that seemed to show that guns had no effect on death rates in the US and Australia. Prof Hemenway argued that these findings were inevitable – not because the firearms truly had no effect, but because of the way the studies were designed.

What about an outright ban?

So far we’ve considered policies that restrict or loosen access to guns in the US. But even measures that sound stringent to American ears are underpinned by the assumption that civilians will still be allowed access to firearms – with the only question being how easy or hard legislators choose to make it.

That’s because the second amendment to the US constitution – the right to bear arms – makes it almost impossible for states or the federal government to block citizens’ access to guns altogether. And it doesn’t look like this will change any time soon. It’s technically possible to overturn a constitutional amendment, but it requires support of a “supermajority” in Congress – more than two thirds of Senators and House Representatives – plus the agreement of 38 of the 50 states.

Politically, this would be challenging to say the least. As one legal commentator wrote in 2018, “even relatively popular ideas with a big head of steam can hit the wall of the amendment process. How much more challenging would it be to tackle individual gun ownership in a country where so many citizens own guns – and care passionately about their right to do so?”

But let’s imagine for a second that somehow the second amendment was repealed and the federal government had much greater powers to ban or remove guns in the US. What might we expect?

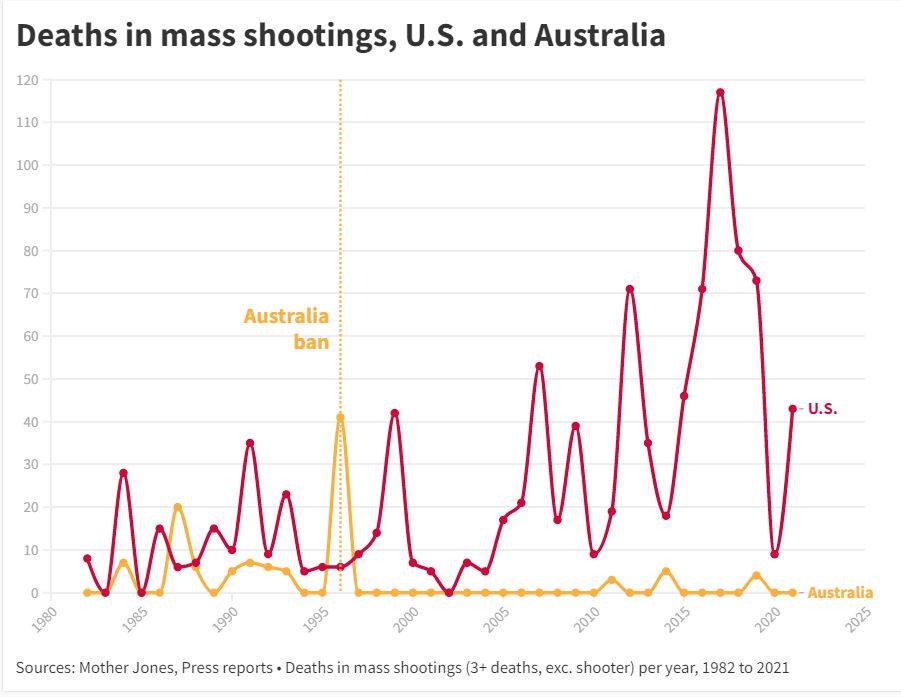

In 1996, the Australian government banned handguns and bought back over 600,000 weapons from the public after a massacre left 35 people dead in Port Arthur, Tasmania. Before then, there had been a number of mass shootings in the country, including five in 1987 alone. Despite its much smaller population, Australia’s annual mass shooting death toll was not that much lower than the US’s – and in some years, like 1987, even surpassed it.

But since the 1996 ban and buyback, 12 people have died in Australian mass shootings, compared to 827 in the US (these figures go up to 2021 and so do not include the Buffalo and Uvalde massacres).

This suggests at least a correlation between banning handguns (which as we’ve seen, are the most commonly used weapons in American mass shootings) and a reduction in the number of mass shooting deaths.

Australia also saw a fall in overall homicide rates after 1996. But again, the question arises: was this caused by the ban and buyback policy, or merely a continuation of earlier declines? The Rand Corporation has looked into this too. Its analysis concludes that “only one study […] provides convincing statistically significant evidence that firearm homicides changed after implementation”. “Specifically,” it continues, “that there was an absolute reduction in female firearm homicide victimization” (women being murdered with guns).

It also cautions that there is no parallel universe in which Australia did not implement the policy to use as a comparison with reality. This lack of the “counterfactual” or “road not taken” scenario is a common problem for scientists across many disciplines, including those looking at gun control – and goes some way to explain why the evidence base has so many gaps.

FactCheck verdict

States with tougher gun laws have lower firearms death rates on average and vice versa. FactCheck analysis using available, if imperfect, metrics suggests that the relationship between the two is strong. We estimate that a 10 per cent increase in a state’s “Gun Friendly” score, as measured by one pro-gun organisation, is associated with a 7 per cent rise in gun death rates in the state.

But we should be clear: this is a correlation, not proof that one caused the other. And the evidence that high-profile proposals to expand background checks to private sales and ban assault weapons will reduce deaths is surprisingly hazy, according to a major analysis that looked at thousands of research papers.

That said, the same report found “moderate” evidence that some gun control measures can reduce homicides – for example, expanding background checks to cover more domestic abusers.

And it revealed stronger evidence still that removing “stand your ground” laws and restricting children’s accidental access to firearms does save lives.