Didn’t make the A-level grade? It’s not the end of the world

For thousands of students expecting A-level results today, the wrong grades may feel like the end of the world. But for some people, it was just the start.

From this morning your life will never quite be the same again. That is the popular belief of A-level results day.

Expect a few certainties, though: a barrage of photographs of teenagers leaping for joy, others in shock as they deal with disappointment. Nationally, if results are better than last year, cries that standards are falling. If the results are worse, wider fears that it has all become too tough.

For the next few days universities will tout their available courses in clearing catalogues. Some will insist that you can still keep your career dreams alive with a degree in engineering and Romanian dance instead of that place you had hoped for at studying medicine at Cambridge. Politicians will try to point-score. Pubs will make a killing in celebration and consolation pints.

And amid all this, thousands of teenagers are expected to make life-altering contingency plans.

If you missed out on the grades you hoped for, take heed. This whole sequence of events plays out every year. And while some struggle, the setbacks are usually temporary. Remember, some of life’s most successful people were not quite where they had hoped to be on A-level results day. But it did not stop them.

The lesson? Missing the A-levels grades might feel like the end of the world. But for many, it is the just the start of theirs.

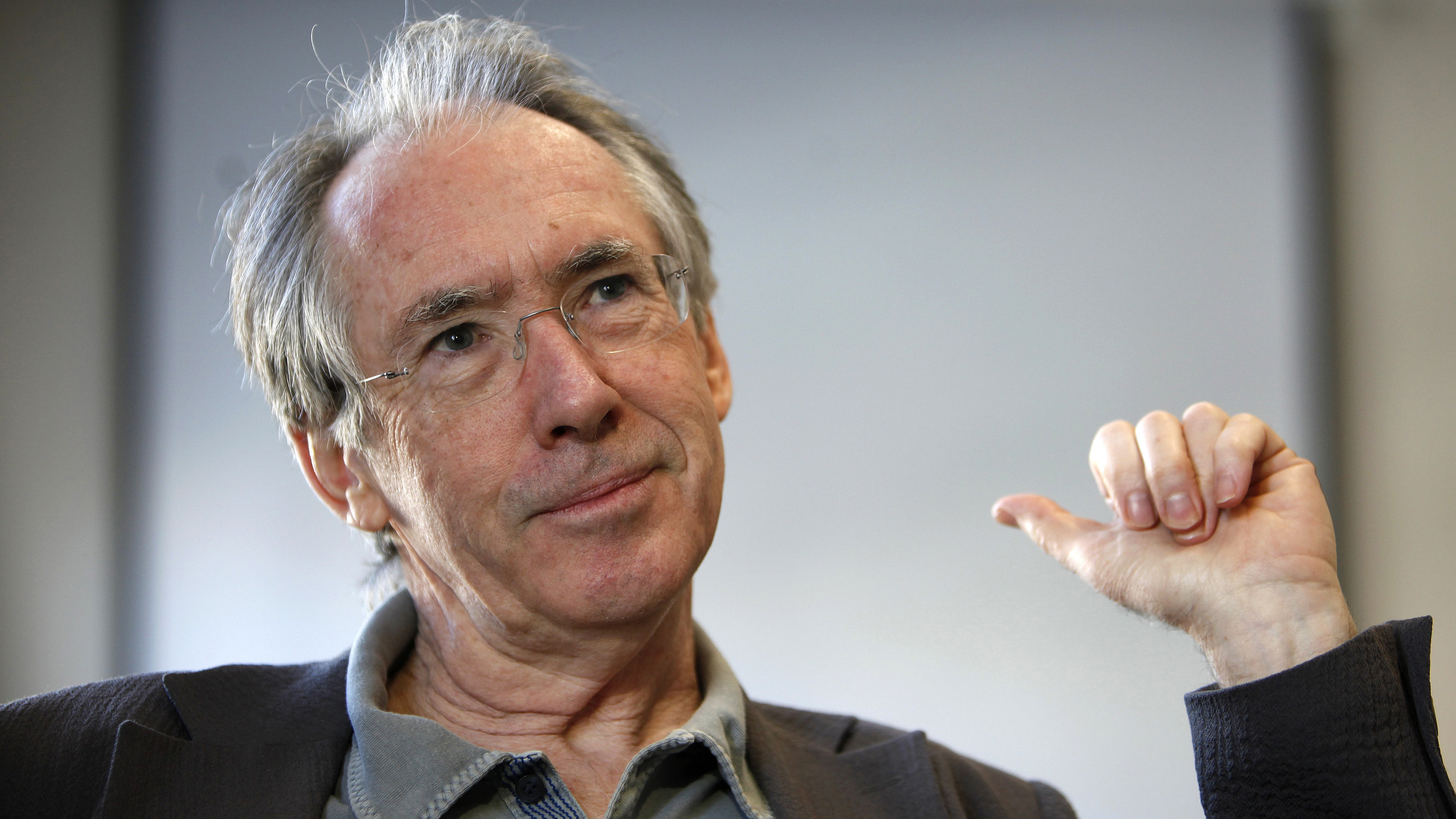

Ian McEwan, author

He is a Booker prize-winner and one of the country’s most revered novelists. But Ian McEwan knew nothing about the life ahead of him when he arrived at Sussex University in the late 1960s.

“I arrived having been one of those kids who was expected to get the scholarship to Cambridge, didn’t do enough work, and found myself at Sussex – and felt disappointment,” he recalled recently.

“For an 18-year-old, I was rather well-read in what was then an uncontested canon. I was disappointed to ï¬nd that my fellow students hadn’t read much beyond their A-level texts. So we weren’t staying up late into the night talking about Wyatt or Milton or Tennyson. I felt very frustrated and even thought I’d leave.”

David Davis, politician

The prime minister’s former leadership rival did not get the A-level grade he had hoped for in zoology due to the distraction of a part-time job and having “not done enough work”.

It meant he missed a university place and worked as an insurance clerk to earn the money to retake his exams. He later gained a place at the University of Warwick (where he met his wife), then London Business School and, finally, Harvard.

When asked for his advice a few years ago, he said: “Don’t give up… It’s only a setback. Life’s about getting over setbacks, not giving in to them.”

Lisa Markwell. journalist

The Independent on Sunday‘s recently appointed editor reflected on A-Level results day and realising “academic work had taken a distant second place to the student union bar, the bands whose tours took in my haunts in High Wycombe and Aylesbury, and a peroxide-blond punk called Tim.”

But within a morning, she says, the emphasis had shifted to “what happens next?”

The rest is history: first an administrative job at Country Life. Then spells at Harvey Nichols magazine, You magazine and the Sunday Times. And finally to The Independent, where she has risen to the top job as editor of The Independent on Sunday.

She wrote: “All I can say is, both as a person who didn’t go to university and as the mother of a child looking down the barrel of terror about educational excellence, a disappointing set of results isn’t the end of the world. It really isn’t.”

Dr Mark Lythgoe, scientist

When neurophysiologist Mark Lythgoe failed to get his desired A-level grades, his parents cried. With three Fs and an E in physics, the future could have been bleak.

But instead it focused the mind. Following a diploma in nuclear medicine at the College of Radiography, an MSc in behavioural biology and a PhD in biophysics, Dr Lythgoe is now one of the leading neurophysiologists and frequently presents programmes for TV and radio.

He once said: “Over the years my sense of failure was my closest friend. I never doubted my abilities but, at moments of darkness when I’ve struggled academically, it’s the thing that’s got me up in the morning. When I gained my PhD at the age of 37, it was one of the happiest days of my life.”

-

Latest news

-

Ex-Trump lawyer Michael Cohen testifies at hush money trial3m

-

Racial hate speech laws being ‘weaponised’ warns National Black Police Association7m

-

‘Hard to believe so many women going through such horrors’, says woman whose baby daughter was stillborn8m

-

Damning report condemns ‘shockingly poor’ UK maternity services12m

-

People ‘expecting the West to stand by Georgia’, says opposition party leader5m

-