Photos from the counter-culture

Revealing photographs by some of the 20th century’s most influential culture icons show unseen sides to Andy Warhol, William Burroughs and David Lynch.

(L-R) William Burroughs (courtesy of William S. Burroughs Estate), David Lynch (courtesy of Nicky Bonne), and Andy Warhol (AP)

They’re three of the key counter-cultural figures of the 20th century: Andy Warhol the pop artist, William Burroughs the cult novelist and the film maker David Lynch.

Now a trio of exhibitions at London’s Photographers’ Gallery shows us another side to these men – the view from behind their stills cameras.

Warhol and Burroughs were camera obsessives, taking many thousands of photographs that informed and inspired their creative processes. The David Lynch show brings the director’s passion for factories to the fore: he has spent three decades photographing industrial scenes around the world, capturing a mood he recreates in many of his films.

Warhol and the camera

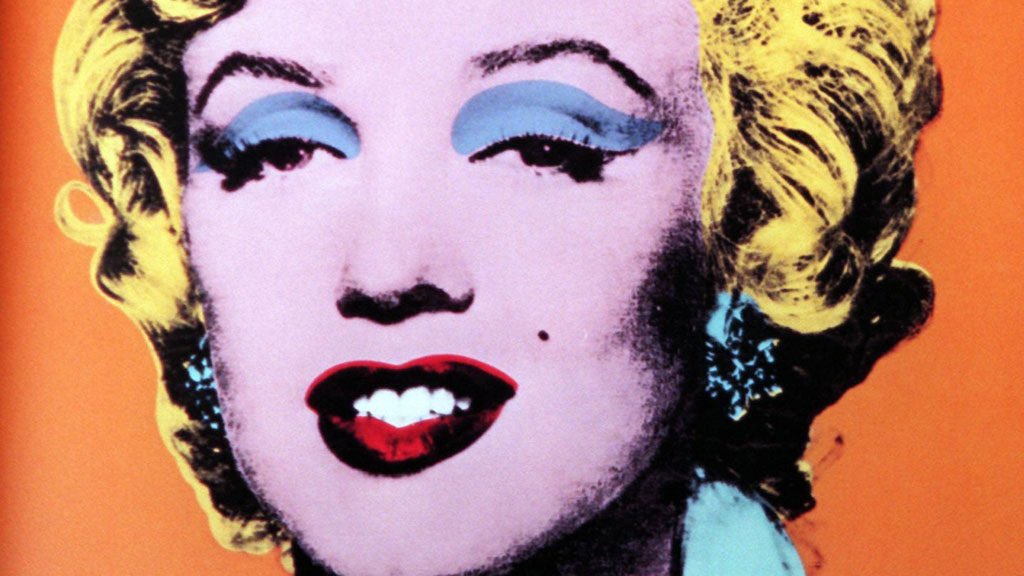

Warhol is well known for using photographs as source materials for his canvases – think Marilyn Monroe, for example.

But later in life, he began taking photographs intensively for their own sake. In 1976, at the height of his fame, Andy Warhol saw a newly-released point-and-shoot Minox 35mm camera at the home of a Swiss collector. It was small and compact – Warhol said it looked like a James Bond camera and asked the owner to give it to him.

When he was refused, Warhol took a detour to a camera shop and bought two. He then proclaimed that he’d divorced from his tape recorder (which he used to record almost everything that happened to him) in favour of the camera and, for the last decade of his life, took up to three rolls a day of film.

In this exhibition called Photographs 1976-1987, so-called Stitched Works of the model Jerry Hall and the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat show Warhol’s continued interest in seriality and the repeated image. These are identical images sewn together and are a photographic reminder of the repetition of images in earlier Warhol canvases.

The 100,000 or so photos that Warhol took, a few of which are shown for the first time in this exhibition, also make clear his equal interest in the remarkable and the mundane. A snap of the paparazzi outside the house of Arnold Schwarzenegger next to an unremarkable newspaper billboard just down the road, bin bags, a gay pride march, trinkets in a flea market – all are worthy of the attention of his lens.

William Burroughs

William Burroughs also took thousands of photographs, most of them left undocumented until recently. It’s the centenary of the birth of the cult author who wrote Naked Lunch and this exhibition is called Taking Shots – a three-fold reference to his obsession with guns, his heroin addiction and his love of photography.

I took a tour with his friend Barry Miles, whose younger 70s self stares out from a photo by Burroughs in the show. Barry Miles described Bill, as he knew him, as a man who was always taking photographs. Using images he came across or created, “he liked to build up pictures of his characters and explore sets”, he said.

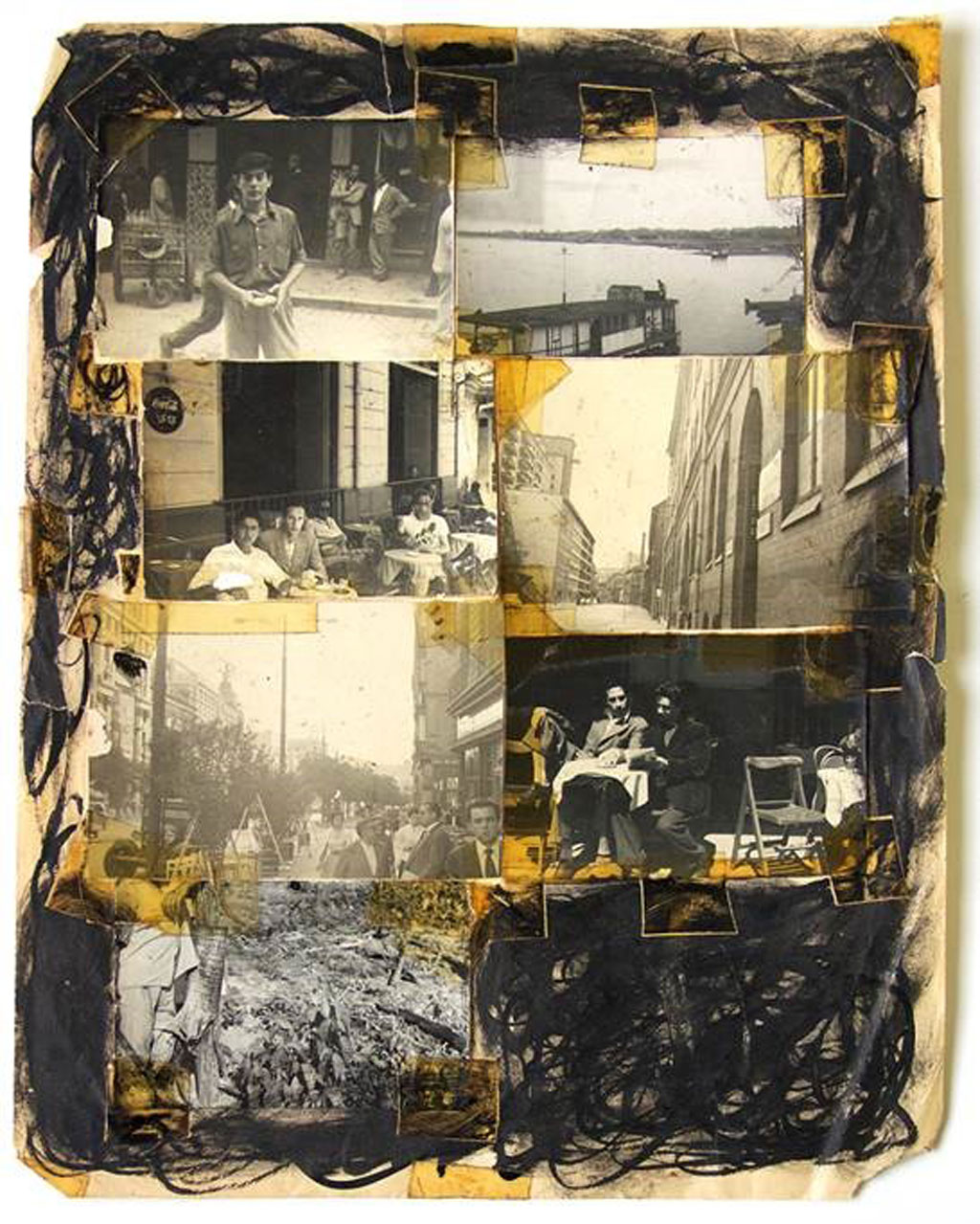

Burroughs also made collages – of photographs of family members, his boyfriends, locations and snippets he tore from newspapers. These were dossiers or templates out of which he’d build up characters or stories for his writing.

William Burroughs is a cult figure. He lived in a communal apartment in New York with Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, he hung out on and off at the Beat Hotel in Paris, spent time in Tangiers and London, where Barry Miles met him. Next month, Miles will publish a biography of his friend: William Burroughs: A Life.

He says he never could keep up with Bill’s high living: “In London, he wasn’t taking so many hard drugs, but he was a serious drinker. There was much looking at his watch and when it was exactly 6pm, there’s be a large whisky and then several more and lots of pot.

“I couldn’t keep up with that. We’d go out to dinner and I’d have to throw up before in order to carry on.”

One of the photos in Taking Shots illustrates the ‘cut up’ style for which Burroughs became known in novels like The Soft Machine. It’s a series of cut up images – half his boyfriend’s face joined to half the Mona Lisa’s, for example.

He’s looking for magical places in his movies and in his photographs Curator Petra Giloy-Hirtz on David Lynch

As Barry Miles explains: “He believed the best way to read a text was to read between the lines. If you slice up newspapers, and rearrange the phrases, you find the real meaning. So by slicing portraits in half, he’s showing us ways of trying to get around the everyday.

“You look and think you know someone, but do you really? It’s about making things fresh and new. He was always looking at ways to stop people being conditioned, to try and read between the lines. We need that more than ever now.”

Image (above right) by William Burroughs: Untitled, 1972 – 73 (Courtesy of the October Gallery)

David Lynch

Photo by David Lynch: Untitled, 2000 (Collection of the artist)

The David Lynch exhibition, The Factory Photographs, is a series of dark and brooding images of derelict factories. The curator Petra Giloy-Hirtz went to the director’s Hollywood studio to go through boxes and boxes of his pictures, never exhibited in Europe before.

Lynch is a filmmaker for whom mood is everything and these black and white photographs mirror the themes of industrialisation and machinery, the flickering light, the dust, the smoke, the atmosphere that are prevalent in his films Eraserhead and The Elephant Man.

Ms Giloy-Hirtz said: “These factories document something that is lost. There’s devastation, waste, destruction.

“He loves these places. He’s looking for magical places in his movies and in his photographs. They have beauty, they tell a story, but above all they have a certain mood.”

The exhibitions at The Photographers’ Gallery run from 17 January to 30 March, 2014.

-

Latest news

-

‘Russian aggressions have never pushed Georgia to deviate from its own path’, says Georgian President5m

-

Why is Georgia’s ruling party so intent on adopting ‘foreign influence’ bill?5m

-

Trump’s lawyers try to paint Michael Cohen as liar out for revenge at trial3m

-

England’s schools told not teach gender identity2m

-

Slovakia PM shooting: Suspect charged with attempted murder3m

-