Russia in 2012: how the mighty are fallen

As Russia struggles to maintain political clout in the Middle East by its support for the Assad regime, Channel 4 News considers if the global reach of the once mighty Soviet empire has dwindled.

Signs of change are emerging in Russia. On Sunday, Russians vote for a new president, with the clear favourite being former president Vladimir Putin.

But the seams of the vast country are fraying. Its citizens are challenging their rulers, and a rare outbreak of civil unrest followed parliamentary elections at the end of 2011. Angry protests gripped Moscow and there were openly voiced allegations of fraud levelled against Mr Putin.

There has also been violence in neighbouring Kazakhstan, a former Soviet satellite state, Russian ally, and home to significant former Soviet-era defence and industrial facilities.

The unrest in Syria will be an unwelcome reminder of the revolutions which saw the break-up of the former Soviet Union. Russia fears what is happening domestically is an echo of the Arab Spring.

As for the future, Vladimir Putin is likely to win the elections – but what sort of country will the new president inherit?

Breakaway republics

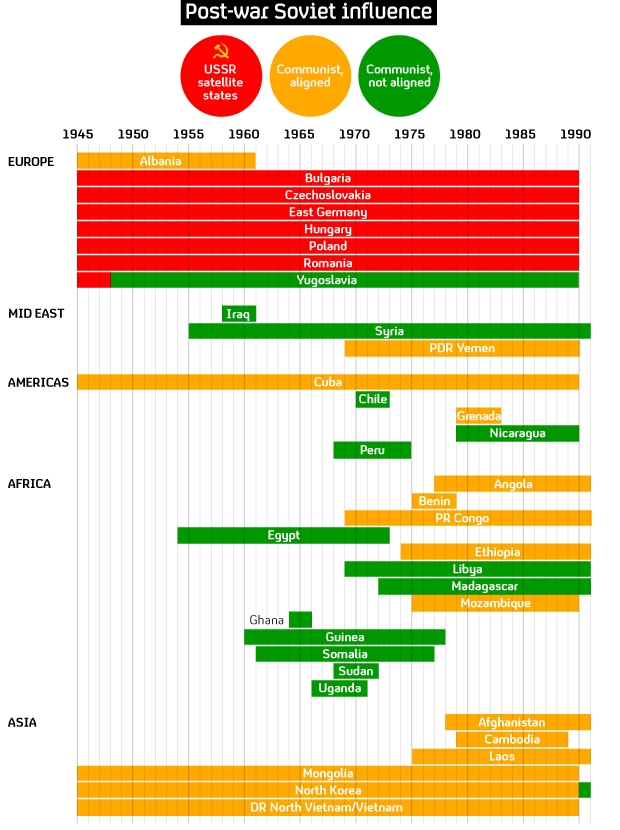

As the country experiences open protest, Russia globally is clearly a shadow of the former Soviet Union. The USSR enjoyed a strong influence in Africa, something which is long gone, China having assumed the mantle of external benefactor.

Russia’s support for the Assad regime was at least partly due to its continued presence in the country via a military base, a vestige of the cold war. Its veto of UN action against Syria showed it can still create impact on the world stage.

But given Russia’s declining international influence, the job for the country’s new leader will be to focus on its role as a regional power and to consolidate its influence in its immediate sphere. One of its major challenges is to reassert its power in its near-abroad, its cushion against powers such as China and Europe.

Read Lindsey Hilsum’s blog about the relationship between Russia and Syria as Homs falls

The millions of dollars it has given in financial aid to breakaway Georgian republics such as South Ossetia and Abkhazia (disputed territories in the south Caucasus – Russia’s support for them weakens unruly Georgia’s domestic power,) ensure that it can exercise power there.

As for the medium term, geopolitical analysts Stratfor predict Russia will aim to rebuild its influence in its former Soviet periphery and build a network with its former states.

Stratfor also say there could be the “formation of a Eurasian union by 2015”, something which might resemble the former Warsaw Pact organisation. But the US and EU have taken to trying to exploit the emerging anti-Kremlin movements – the US has funded anti-Kremlin groups – in order to promote democracy in the region or, as the Russian government no doubt sees it, to destabilise the regime.

Despite the protests, Vladimir Putin is still popular, and the lack of a credible well-supported opponent means his power is unlikely to be compromised.

The sheer size of the region over which Russia has exercised influence, and the fact that Russian energy keeps Europe’s lights on, means that it still has some cloud as a geopolitical force.

What will be important is how domestic unrest develops and whether or not the new President Putin can broker deals among former satellite states and breakaway regions to ensure a modicum of cohesion for the region. Only then can Russia consider redefining its role internationally.

-

Latest news

-

As India goes to the polls in the world’s largest election – what do British-Indians think?6m

-

Tees Valley: Meet the candidates in one of the biggest contests coming up in May’s local elections4m

-

Keir Starmer says public sector reform will be a struggle7m

-

Nicola Sturgeon’s husband Peter Murrell charged with embezzlement of funds from SNP1m

-

Ukraine might finally get $60billion in American weapons and assistance to defend against Russia3m

-