Oil: a political commodity

The EU oil embargo on Iran shows how “black gold” can determine the decision-making of countries across the globe. But what does the future hold? Channel 4 News speaks to the experts.

Oil has already hit the headlines in 2012, with the EU oil embargo on Iran.

While the ultimate retaliation threat from Iran – that it would close the Straits of Hormuz, through which 20 per cent of the world’s oil supply travels – did not materialise, experts are still concerned over the impact of the embargo itself, not least on fragile European economies like Greece, which imports a quarter of its oil from Iran.

David Strahan, author of The Last Oil Shock: A Survival Guide to the Imminent Extinction of Petroleum Man, told Channel 4 News: “It’s more political than just oil – Iran is a biggie.”

But the situation appears to have calmed after the US displayed its military muscle (and intentions), leading an international flotilla of warships through the channel.

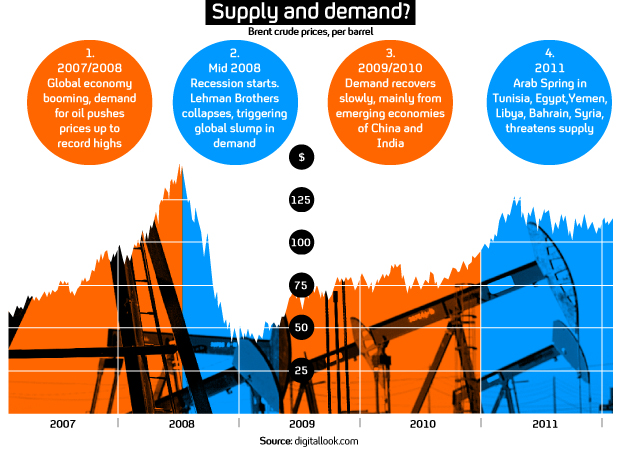

Fears of violence aside, the increasing tension does not seem to have caused a spike in oil prices, which are hovering around $113 a barrel. The Arab Spring worried the markets more – unrest in the key oil-producing region of the Middle East saw oil prices rocket up to a two-year high of $118 in early 2011, as Libya went offline. The markets also priced in fears that Saudi Arabia, the world’s second-biggest producer after Russia, could be next.

As it turned out, protests in Saudi Arabia were suppressed. Even in Libya, which saw a bloody civil war and regime change, production has now resumed almost to pre-Arab Spring levels.

John Mitchell, an energy expert at international think-tank Chatham House, told Channel 4 News the relative return to normality in the oil markets, particularly in Libya, was a “lesson” for panicked observers.

“Over the year, the concern has subsided because the Libyan situation has been resolved. That’s a lesson, given the stabilisation of the political situation – there was quite a lot of damage to facilities but production can be very resilient,” he said.

“It’s not anything like in the 1980s, after the second oil shock. This all hinges around two things – one is the fact that the importing countries, the western countries, now have an emergency sharing scheme.

“The other is that Saudi Arabia has been investing a lot in expanding its capacity. If you suggest we couldn’t rely on Saudi Arabia, that’s a different issue – but that’s not being suggested.”

What does the future hold?

In fact, for all the fears over oil and accusations that foreign wars are about “black gold” as superpowers protect their supply, there is also an argument that price spikes are just as much about increasing demand.

So if the global economy is growing, oil prices go up; if it is tanking, they go down – regardless of political events in the Middle East or anywhere else.

It was excess demand for oil as the global economy boomed in 2008 – coupled with the weak dollar – which saw oil prices spike at $145 a barrel in 2008. And it was the subsequent financial crisis that saw prices crash as demand fell.

But the supply side is important too – which is why prices leapt up again during the Arab Spring. And it is the insecurity of the world’s future supply of oil which also has a major political dimension, experts told Channel 4 News.

However, Chatham House’s Mr Mitchell believes the world has some breathing space.

I don’t see a staircase of oil prices into the sky. John Mitchell, oil expert at Chatham House

“The world can provide the supply of oil at the present levels for several decades, and even some increase,” he said.

“The situation is being transformed for oil as for gas by the development of new technology which allows us to extract oil from shale. Also demand is flattening off to some extent in the US and the EU, even in China. It’s a bit of a yo-yo, but I don’t think we are heading into an inevitable shortage situation, and I don’t see a staircase of oil prices into the sky.

“Having said that, there is always the risk of disruption.”

David Strahan agrees that demand, particularly from the US, could decrease as a result of shale gas. It could also decline as countries get serious about meeting environmental commitments – either through more enthusiasm for electric cars, or because ordinary petrol cars will become considerably more efficient.

There is a school of thought that the US could even be self-sufficient as a result of shale technology – although Mr Strahan is not convinced. But even a slight change in US reliance on global oil providers could have profound political implications, he told Channel 4 News.

“That might change their attitude towards the rest of the world. They will be more confident, less dependent on Arab states and Venezuela, so there will be an impact – it could make them bolder, or more isolationist. You cold argue either.”

Whether shale gas makes a difference or not, Mr Strahan believes the general decline in oil production will have political implications.

“Oil has always been fantastically important. There’s no doubt that it has explained America’s Middle East policy and all sorts, and oil depletion can only make it more so,” he said.

“Every year depletion means we lose around 3.5 million barrels of daily capacity, if we do nothing. That has to be replaced before anything else happens – it’s the treadmill that people don’t get about the oil industry, and it’s getting harder to fill that hole every year. And to fill it, the sort of deposit that has to be exploited is becoming more expensive and more difficult, and that’s why the price is where it is.”

He thinks further trouble or enroaching depletion could even push the price to the highs of $150 a barrel. And it is this volatility which is one of the reasons he advocates the world cutting its ties with oil.

“There are three good reasons to get off oil as quickly as we can,” he told Channel 4 News.

“One, the traditional reason: carbon. Two: it’s running out. And three: oil price volatility. That there is not enough to go round is certainly true – so we are going to have a series of oil price spikes and recessions because oil is so critical to economic growth? Oil prices spikes have precipitated 10 out of the last 11 US recessions.

“These oil prices spikes are here to stay unless we decide to change our transport fuel of choice. I don’t think oil is the answer – getting off oil is the answer.”