Libya’s rebel movement: radicals or democrats?

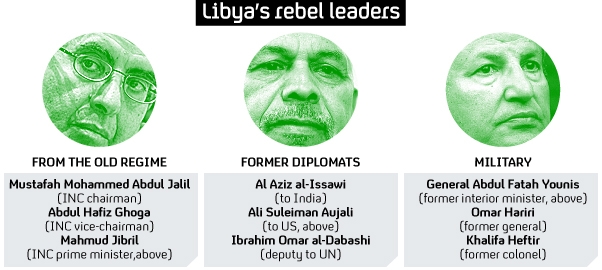

We look at the most prominent members of Libya’s rebel movement – an ad hoc coalition of former Gaddafi men, soldiers, democrats and radicals.

David Cameron promised “better days ahead for Libya” at the London conference on 29 March, and pledged: “Just as we continue to act to help protect the Libyan people from the brutality of Gaddafi’s regime, so we will support and stand by them as they seek to take control of their own destiny.” US President Barack Obama, meanwhile, has vowed that the US will “work with other nations to hasten the day when Gaddafi leaves power”.

But Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has admitted her country does not “know as much as we would like to” about the rebel leaders waiting in the wings to replace Colonel Gaddafi. This is because Libya – like Yemen, Tunisia and Syria – has been led for decades by a dictatorial president who has tolerated little or no opposition.

Where post-Mubarak Egypt could call on an opposition figure of international standing in Mohamed el-Baradei, and a long-established political party in the Muslim Brotherhood, there has been no political class in Libya during Gaddafi’s 42-year reign.

Essentially administrative

Nor is it always easy to pinpoint the ideological hinterland occupied by the opposition figures who have emerged in recent weeks. The Interim National Council (INC), established in Benghazi in February, may be “the only game in town so far”, according to Sir Richard Dalton, former UK ambassador to Libya and an associate fellow at Chatham House. But other than the legend “Freedom, Justice, Democracy” on its website, it is hard to identify a clear set of INC beliefs.

The INC published A Vision of a Democratic Libya on 29 March, to coincide with the London conference. It is a document which espouses western democratic ideals while promising “a State that draws strength from our strong religious beliefs in peace, truth, justice and equality”.

At this stage, though, the INC’s purpose is essentially administrative: to set in place institutions which allow eastern Libya to be governed during the present turmoil, and to provide a focus for others across Libya who want to join in the fight against Colonel Gaddafi.

Al-Qaeda threat

Last week a Libyan rebel leader from Derna, east of Benghazi, told the Italian newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore he had recruited “about 25” Libyans to fight alongside insurgents in Iraq, claiming some had now returned and were fighting Gaddafi forces in Ajdabiya.

Abdul Hakim al-Hasidi’s words stoked fears that Libya’s rebel movement was not made up simply of west-loving democrats but included – as Colonel Gaddafi has repeatedly claimed – a significant al-Qaeda element. Those fears were reinforced when Nato’s Supreme Allied Commander, James Stavridis, told the Senate Armed Services Committee on 29 March that “flickers” of intelligence indicated the existence of al-Qaeda or Hezbollah affiliations within Libya’s opposition.

Such suspicions can be traced back to documents uncovered by coalition forces in a raid near Sinjar, on Iraq’s Syrian border, in October 2007, which revealed details of foreign nationals who had entered Iraq over a 12-month period from August 2006.

Rebel momentum

Analysis of the documents by the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) at West Point, in the United States, revealed Libya, with 112 fighters, was the second most common nationality among the 595 records that included the fighter’s nationality. On a per capita basis (“number of fighters per one million residents in home country”), Libya was by far the biggest contributor to the fighting. What is more, 85.2 per cent of the Libyan fighters had registered their “work” as “suicide bomber” or “martyrdom seeker”.

Significantly, the town of Derna (or Darnah) provided 52 of the Libyan fighters – “far and away the largest per capita number of fighters in the Sinjar records”. Derna was followed by Riyadh, the Saudi capital, and Benghazi, also in eastern Libya. The CTC report asserts that “Both Darnah and Benghazi have long been associated with Islamic military in Libya” and notes the “increasingly cooperative relationship” between the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group and al-Qaeda.

RUSI’s Shashank Joshi believes eastern Libya’s rebel movement is a broad-based grouping and not made up simply of radicalised young people. He told Channel 4 News: “Many of those offering knee-jerk reactions about al-Qaeda’s influence should perhaps suspend judgement until they have a clearer sense of what is happening.”

But he also warned: “Rebel movements tend to have a certain momentum, with the danger of radical elements splitting from the main currents. And even the main currents, if they are sufficiently militarised and resentful towards the regime, can be dangerous.”

The ebb and flow of of military success in Libya is reflected in the changing and emerging faces within the country’s fledgling rebel movement. Here are some of the most prominent players on the Interim National Council.

Mustafah Mohammed Abdul Jalil

Perhaps the best known rebel leader, Mustafah Mohammed Abdul Jalil resigned as Colonel Gaddafi’s justice minister when the uprising began and is now INC chairman.

“He had a high reputation for principle and independence of mind as a judge and justice minister,” Sir Richard Dalton told Channel 4 News, “and I have a lot of confidence in him as a good person working in the interests of the Libyan people.”

Some reports say Jalil’s influence has waned in favour of Mahmud Jibril (see below) as the rebel coalition struggles to overcome military setbacks and the political chaos within its ranks.

Mahmud Jibril

In his capacity as INC prime minister, Mahmud Jibril was in London on 29 March, meeting UK Foreign Secretary William Hague ahead of the London conference. Like Jalil, Jibril is highly thought of in western circles, having established a career as an administrator. He was running Libya’s National Economic Development Board when the turmoil in north Africa spread to Libya in February.

Sir Richard Dalton calls Jibril “an impressive academic and administrator who probably knows more than anybody about how the Libyan economy and society works at micro and macro level”. He notes also that Jibril had ties with Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, the colonel’s LSE-educated son. His surprise resignation in January 2010 was rejected by President Gaddafi – according to some because Saif would not let him stand down.

Jibril features in a WikiLeaks cable dated May 2009. The writer characterises him as “a serious interlocutor who ‘gets’ the US perspective” and is “not shy about sharing his views of US foreign policy, for example, opining that the US spoled a golden opportunity to capitalize on its ‘soft power’ (McDonald’s) after the fall of the Soviet Union.”

Abdul Hafiz Ghoga

Benghazi-based Ghoga is vice-chairman and spokesman for the INC, having tried earlier to establish a rival group to coordinate the rebel response in Libya. A human rights lawyer, Ghoga was involved in legal representation for the families of some of those killed in the notorious Abu Salim prison massacre in 1996.

Earlier in March, as the west struggled to achieve a coordinated approach to the Libyan crisis, it was Ghoga who warned: “The Libyan people are facing genocide, the annihilation of an entire population through the use of air power and heavy artillery.”

In a recent interview with the Ashard al-Awsat newspaper, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi was dismissive of his influence, maintaining that: “Ghoga is backed by no more than a handful of people, and they do not represent the Libyan people.” He went on to cast doubt on Ghoga’s allegiances, claiming: “Two weeks ago he was sitting in Colonel Gaddafi’s tent cheering and applauding.”

Ali Aziz al-Issawi

The former Libyan ambassador to India is the transitional council’s foreign affairs spokesman. He became the country’s first envoy to resign, standing down in protest at the crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators.

The INC website says al-Issawi occupied the position of Minister for Economy, Trade and Investment under the Gaddafi regime, as well director general for Libya’s Centre of Export Development.

Other notable Libyan envoys to have relinquished their posts in recent weeks include Ali Suleiman Aujali, ambassador to the United States, and Ibrahim Omar al-Dabashi, deputy ambassador to the UN.

Omar al-Hariri

The INC’s head of military affairs was involved in the 1969 coup which brought Colonel Gaddafi to power. Seven years later he was involved in an abortive plot to overthrow Gaddafi, for which he was sentenced to death. He languished in jail for 15 years, until his sentence was commuted and he was placed under house arrest.

Earlier this month al-Hariri, a popular commander, told a news conference: “We will fight, and we are powerful. We know how to fight and we know how to win.”

General Abdul Fatah Younis

Libya’s former interior minister and head of the country’s armed forces, General Younis is described by Sir Richard Dalton as “a very significant figure”. He defected to the anti-Gaddafi camp on 20 February, after which a succession of army posts throughout eastern Libya fell to the rebels.

Younis, who was also involved in the 1969 coup, had previously been regarded as a regime loyalist, and reports suggest some INC members remain wary of his true allegiance.

-

Latest news

-

Laughing Boy: New play tells the tragic tale of Connor Sparrowhawk5m

-

Sewage warning system allows some of worst test results to be left off rating system, analysis shows3m

-

Post Office inquiry: Former CEO didn’t like word “bugs” to refer to faulty IT system4m

-

Israeli soldier speaks out on war in Gaza12m

-

PM’s defence spending boost should be ‘celebrated’, says former Armed Forces Minister4m

-