Why has UK failed to exploit ties with India?

The balance of power has shifted considerably as the foreign secretary and chancellor attempt to make key gains in the United Kingdom’s economic partnership with India.

Western governments have rushed to visit the country’s new prime minister, Narendra Modi, drawn by the prospect of multi-billion pound deals as the government prepares to open up the nascent defence industry to foreign investment.

Senior politicians from France, US and Russia arrived in India in quick succession in June to pay court to the new premier since his landslide election victory in May. While the UK has had a less tenuous relationship with Modi than the US, which denied him a visa in 2005 over his “associations” with the 2002 Gujarat riots as well as imposing an arms embargo in 1998, it has been far from stable.

Modi intends to build up India’s military capabilities and gradually turn the world’s largest arms importer into a heavyweight manufacturer – a goal that has eluded every prime minister since the country’s independence in 1947.

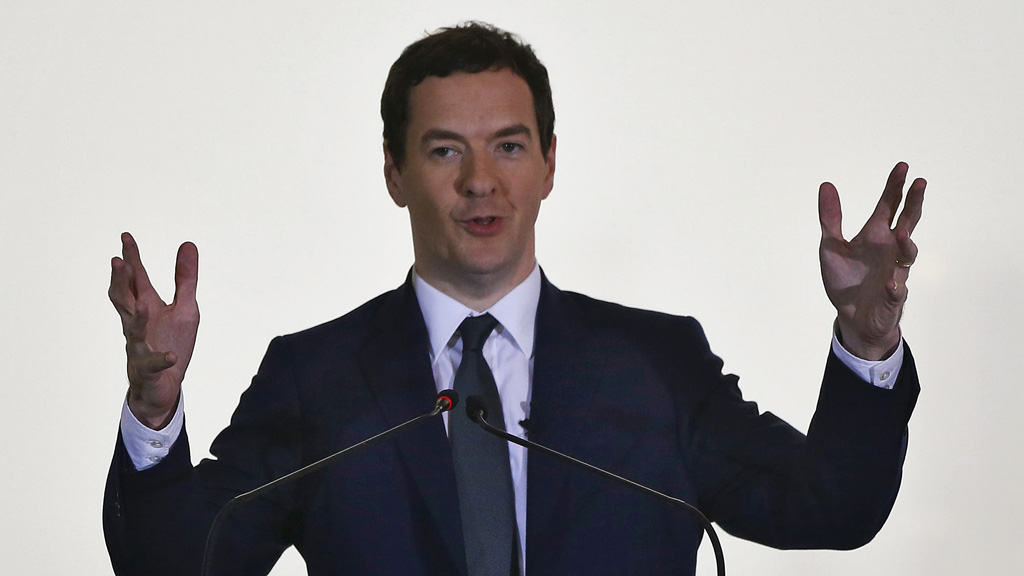

The new government hopes to raise the cap in foreign investment, including allowing complete ownership of defence projects – which is why both George Osborne and William Hague have sought to strike multimillion-pound defence deals with the leader.

UK fails to secure defence deal

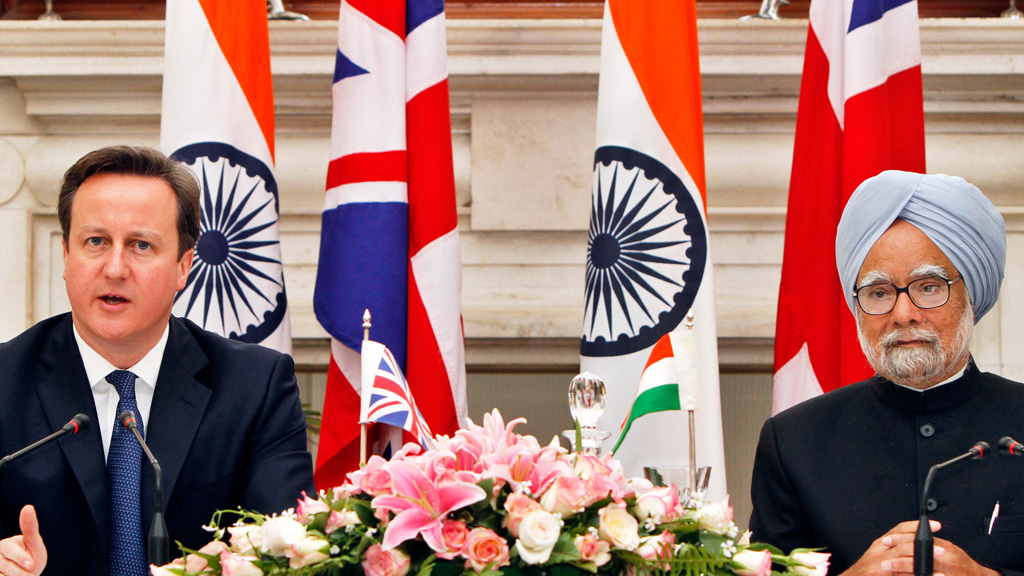

This it is not the first time the UK has tried to woo India into a defence deal. In February 2013, Prime Minister David Cameron pushed for the sale of Eurofighter Typhoon fighter jets for the Indian Air Force, in the country’s biggest-ever military contract.

But the UK failed to secure its position, and Manmohan Singh, the then prime minister, opted for the French Dassault Rafaele jet. And while there were more obvious reasons behind the decision – including the fact that India has had extensive military ties with France and the Rafaele offer featured substantially lower costs of ownership – it was clear that Britain had been losing share among opinion-formers in the country.

According to Shashank Joshi, a research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), France is “reliable when push comes to shove”. This was underlined by France’s refusal to condemn the 1998 nuclear tests carried out by India, and its collaborative approach during the 1999 Kargil war with Pakistan, when it allowed India to modify the Mirage 2000 jet. Mr Joshi says that France is “really remembered as a diplomatic anchor”.

Britain’s Modi boycott

The Anglo-Indian relationship waned during the Labour years. It was sometimes seen to be of less importance than the diaspora Pakistan vote in the marginal seats in the West Midlands and the north of England.

In 2009, when David Miliband was Labour’s foreign secretary, India’s main opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) remarked, “In recent years, there has been no bigger disaster than Miliband’s visit,” after he gave a lecture on the Kashmir dispute in India.

Not long after the 2008 Mumbai Islamist terrorist attacks, Mr Miliband went to the Taj Mahal Hotel in New Delhi to lecture Indians that “resolution of the dispute over Kashmir would help deny extremists in the region one of their main calls to arms and allow Pakistani authorities to focus more effectively on tackling the threat on their western borders”. The remark left a bad taste in the mouths of many staunch BJP supporters.

In recent years, there has been no bigger disaster than Miliband’s visit. Bharatiya Janata Party

In the aftermath of the 2002 killings of Muslims during the Gujarat riots, Britain was among many western countries to enact a de facto boycott of Modi. That ended in October 2012 when the UK saw Mr Modi’s rise. There had been widespread calls from Britain’s Gujarati community to end India’s relationship with the UK.

Thus when Mr Cameron visited India as leader of the opposition, he identified that the UK was losing share of trade and foreign direct investment. Between 1999 and 2009, the UK slipped down to 22nd place from second place among India’s trading partners, overtaken by Belgium. The retail sector also remained closed to the likes of Tesco. Even in 2013, the UK did not feature among the top 10 exporters to India, but did subsequently crawl back to eighth place as a major importer of Indian products.

And it seems that India is not planning to open up the retail sector to foreign direct investment, according to the British deputy high commissioner for eastern India. Scott Furssedonn-Wood told local newspaper the Hindu: “This (FDI in multi-brand retail) is a decision of an individual country and we respect it.”

‘Good days are coming’

Despite the tumultuous association, Mr Osborne remains positive for future India-Britain relations. Speaking in Mumbai on 7 July, he said: “Good days are coming for the financial partnership we can forge to build, literally, the infrastructure of the future.”

Gandhi was father of democratic India. Can announce we’ll honour his memory with statue in front of mother of parliaments in parliament sq

— George Osborne (@George_Osborne) July 8, 2014

It seems an ideal time for Britain then to erect a statue of Mahatma Gandhi outside the palace of Westminster in Parliament Square. The chancellor said it would be a fitting tribute to the “father of democratic India”, as the UK tries to win favour with the growing nation.