The claim

“No Government has done more than this one to crack down on tax evasion and aggressive tax avoidance.”

“No Government has done more than this one to crack down on tax evasion and aggressive tax avoidance.”

David Cameron, 10 February 2014

The background

Allegations that HSBC helped wealthy clients get out of paying millions has put tax dodging back at the top of the news agenda.

The government is busily defending its record, with the Prime Minister insisting that the coalition has done more than any other to crack down on tax evasion (illegal) and avoidance (legal but immoral).

It’s certainly true that the government has introduced a long list of measures designed to close loopholes that let people pay less than their fair share of tax.

But how well are these policies working? It’s a straightforward question, but one that is surprisingly hard to answer.

The analysis

We’ve counted no fewer than 56 changes brought in by the coalition in various budgets and autumn statements in an effort to stamp out various forms of tax tomfoolery.

But what does it all add up to? And who is keeping track of how much extra money is really coming in?

In the last Autumn Statement, the Treasury said: “The measures taken so far this Parliament to tackle aggressive tax planning, avoidance and evasion add up to £7.6 billion in additional revenues in 2015-16.”

That sounds like a lot, but Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs (HMRC) was supposed to be bringing in £9bn of additional money a year by then, according to a deal the taxman struck with the Treasury in 2012.

The independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) said in its most recent forecast that some anti-avoidance measures had brought in more money than expected and some less, but overall “significantly less has been raised in total than originally expected”.

The biggest disappointment was the 2012 UK-Swiss tax agreement, in which Brits with a Swiss bank account were subject to a one-off tax. This was supposed to net £5.3bn for the exchequer but only raised £1.9bn.

The OBR doesn’t tell us what “significantly less” means and it told us it “cannot verify” the government figure of £7.6bn in 2015/16. Clearly that number must be a projection, and we have seen that projections can be wildly wrong.

Does all this mean that we were hoping for £9bn but are really predicted to get £7.6bn? We have asked the Treasury to clarify but haven’t received an answer yet. [*UPDATE: see below]

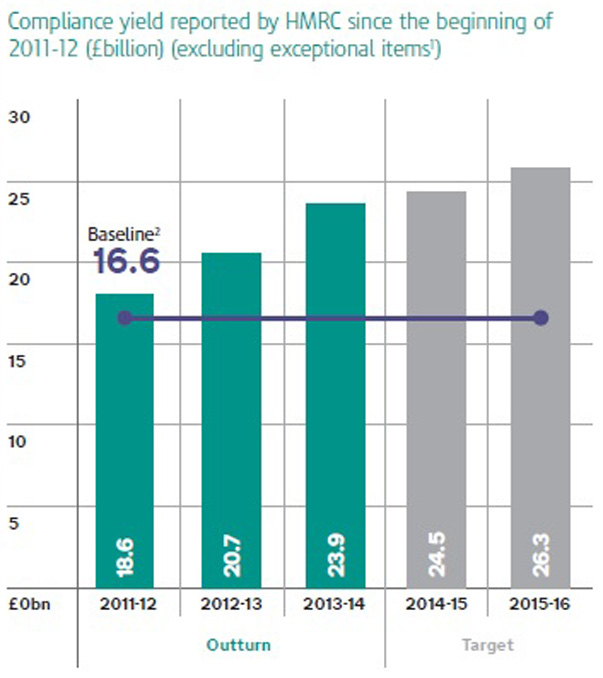

HMRC provides numbers on how much it expects to raise from “compliance” activity – efforts to reduce fraud, evasion and avoidance in any given year.

But the cross-party public accounts committee has criticised these numbers as being unfit for purpose.

The coalition basically struck a deal with the taxman, giving it about £1bn more funding than was originally promised, as long as its evasion and avoidance teams brought in more money – finally set at £9bn a year by 2014/15.

For a couple of years, HMRC reported that it was making great strides towards hitting this target.

But last year the National Audit Office (NAO) found that the organisation had made a serious error when it agreed its targets with the Treasury. It was working from a baseline that was £1.9bn too low, which exaggerated its achievements.

That meant that the taxman had repeatedly (if inadvertently) misled the public and parliament about how much extra tax revenue it was raking in, the public accounts committee noted. It also failed to spot the mistake itself.

HMRC has now revised its claims down – but it says the gains it has made still add up to billions of extra cash for the public purse. Even counting from the new, higher baseline of £16.6bn, the tax authorities still supposedly contributed more than £7bn extra in 2013/14.

But that isn’t a pile of cash sitting in a bank vault at HMRC towers. It’s a hypothetical estimate of the effect of legislative changes, predictions of future revenue, and money that will not be lost to the exchequer thanks to HMRC’s efforts.

Only half is “cash collected” – and even that doesn’t mean what you think it means. HMRC chief executive Lin Homer told the committee: “Even some of the cash is due and may not all be literally in the bank at the end of the year, but it will come in.”

Overall, the National Audit Office noted “different levels of certainty and precision” in the way these various estimates are calculated but said: “The methodology and processes HMRC used to estimate compliance yield in 2013-14 were sound, and that the measure provides a reasonable proxy for the beneficial impacts of its compliance work.”

However, everyone agrees that changes in the methodology means the taxman can no longer claim to have made long-term improvements.

The organisation has published figures in past comparing its recent successes with the low revenues of 2005/06.

But after criticism from the NAO and the public accounts committee, it says: “In light of the error we have found in our baseline, we now recognise it would be inappropriate to compare directly compliance yield outturns as they have been measured since 2011-12 with earlier years.”

This suggests that we might never really be able to say whether this government has done substantially better than the previous one on tax, since a fair comparison can’t really be made with the sums collected before 2011/12.

The verdict

Is Mr Cameron right to say that this government has done more than any other to tackle tax dodging?

The most recent government estimate of the money brought in by the various measures it has brought in is £7.6bn a year by 2015/16, but we’re completely in the dark about how this sum was calculated and whether it actually means that we will miss out on the £9bn-a-year target set out in 2012.

HMRC does provides detailed figures on its “compliance yield”, but these have been called into question by the public accounts committee.

The annual number is an estimate, not a count of actual money in the bank, and the committee has concluded that “the measure currently lacks the certainty and clarity for Parliament and taxpayers to fully understand it or use it to hold HMRC to account over the longer term”.

Another way of looking at HMRC’s efforts is by measuring the size of the “tax gap” – another highly theoretical but officially approved measure of how much tax is left unpaid every year thanks to avoidance and evasion.

According to HMRC’s own figures, the gap widened last year after falling every year since 2005:

*UPDATE: HMRC have now told us the £7.6bn Treasury figure and its target of £9bn are “two entirely different things”. The £9bn “refers to compliance yield – which is a measure of HMRC’s performance on compliance and it reflects both cash collected to close the tax gap and the value of revenue losses prevented both now and in the future. HMRC is still on track to meet that target”. And the £7.6bn “refers to policy measures that this government has announced this Parliament to tackle avoidance, evasion and aggressive tax planning in various fiscal events…it relates to the amount of scoreable yield – so tax revenue we forecast we will raise from those measures in 2015/16”. If the OBR is right, that £7.6bn is “significantly less” than what was originally expected… but no one will tell us how much less.