David Cameron reportedly told Conservative backbenchers to expect what was described as a “big bang” policy announcement on immigration this week.

This has led to speculation that the prime minister might try to change the EU rules on freedom of movement to restrict the numbers of migrant workers coming to Britain from other member states.

Mr Cameron has said he will try to renegotiate the terms of Britain’s membership of the EU if the Conservatives win a majority at the next election. This would have to take place by the end of 2017, when he has pledged to hold an in/out referendum.

Many commentators have linked the hints of a strong new line on immigration to the growing threat of Ukip, to whom the Conservatives – along with other parties – have been haemorrhaging support.

But I thought Ukip was all about Europe?

The party puts withdrawing from the EU first in its list of priorities, but polling suggests most Ukip supporters are more worried about immigration than Europe – or indeed any other issue.

This is what happened when pollsters from YouGov asked supporters to rank the most important issues facing the country.

Note that 53 per cent of all voters polled here (not just potential Ukip voters) said “immigration and asylum” was the issue that mattered most to them, making it the second most important concern among the general public.

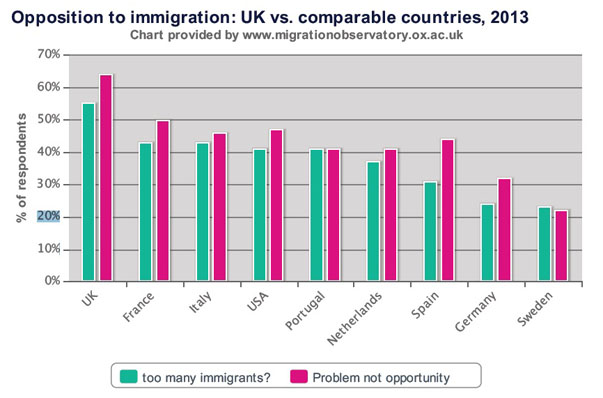

Compared to many similar countries, the UK tends to be more negative about immigration

Aren’t there already restrictions on immigration?

The Conservatives have said they want to see net migration fall to the “tens of thousands”. But the latest estimate from the Office for National Statistics put long-term net migration to the UK at 243,000 in the year ending March 2014, up from 175,000 in the previous 12 months.

The government introduced restrictions on non-EU immigration in 2012, and the influx of people from outside Europe did fall for three years, before increasing again in the latest figures.

Net migration of EU citizens, which the government is basically powerless to control, has increased.

Immigration from within the EU remains high in Britain, hovering around the 2.5 million mark, with most people in work. Only Germany attracts more EU migrants.

What is David Cameron going to do now?

The short answer is: we don’t know yet.

Today, while campaigning in Kent, the prime minister said: “We need further action to make sure we have more effective control of migration.”

This has led to much talk of the government seeking to pull an “emergency brake” allowing Britain to impose restrictions on the fundamental right of freedom of movement currently enjoyed by EU citizens.

How does this “brake” thing work?

Passing new EU laws often used to require a unanimous vote, but with a growing number of members states, unanimity was becoming difficult to achieve. So the 2007 Lisbon treaty brought in qualified majority voting in many policy areas.

But countries have an “emergency brake” which they can use to avoid passing laws that affected fundamental aspects of their social security system or legal system.

The “brake” isn’t a straight opt-out. It means the new law is put on ice while the European Council discusses it, but the mechanism at least lets governments kick unpopular legislation into the long grass.

EU law experts we have spoken to are sceptical about how the “emergency brake” could be used in respect of putting a limit on immigration, which would mean changing the fundamental principle of the free movement of workers.

Professor Damian Chalmers from the London School of Economics told us: “This is not used as a threshold for levels of migration. If we wanted to put a quota on migration and stop movement when we hit 2.5 million EU nationals in the UK, that would clearly violate the EU treaty and they would have to renegotiate it.”

Professor Jo Shaw from Edinburgh University told us: “In my judgment, Cameron is not likely to be able to achieve the ’emergency brake’ referred to in press reports in conjunction with the other EU member states.

“To do so would be to invite the complete unravelling of the system of the free movement of persons, and I don’t sense any particular appetite on the part of the member states to step on this road.

“I think that’s a reasonable judgment for member states to make, because in truth free movement of persons is a foundational issue for the EU, even more so than the euro.

“To unravel that means the end of the EU as we know it – and I’m sure Cameron, who is perfectly capable of working these things out, can see that and knows that he won’t get very far.”

Is there anything Mr Cameron can do?

He might be able to tighten the rules on migrant workers having the right to claim benefits after arriving in the UK. This would not require a major negotiation of the EU treaty, and Mr Cameron might have some support from other member states.

Germany, Austria and the Netherlands among others have laid out plans to restrict welfare rights for unemployed migrants.

But Germany has made it clear that its planned reforms do not undermine the fundamental principle that EU citizens should be able to work in other countries without a permit.

So Mr Cameron may find there is some appetite for toughening up on migrants’ rights to claim benefits. But that is not the same as preventing people from coming to the UK to work.

A European Commission-sponsored study last year found that employment was “the key driver for intra-EU migration” and found no evidence of people emigrating with the intention of living off welfare.

Prof Chalmers told us: “There is lots of support in most of the EU15 states on restrictions on the right to claim and all it would require is secondary legislation. I think Cameron is pushing at an open door there.

“But I haven’t heard any support for restrictions on the right to work.”

In any event, a new measure to curb so-called “benefit tourism” would hardly be a “big bang” announcement. Mr Cameron already put it on the seven-point shopping list for renegotiation he laid out in an article for the Sunday Telegraph earlier this year.