Boris Johnson launched his official campaign to succeed Theresa May yesterday.

The former foreign secretary made much of his record as mayor of London to demonstrate his leadership credentials.

But he didn’t mention some of the blunders and broken promises from his time at City Hall. Let’s take a look.

Rough sleeping

In 2009, Mr Johnson promised to end rough sleeping within three years. He said: “It’s scandalous that, in 21st century London, people have to resort to sleeping on the streets, which is why I have pledged to end rough sleeping in the capital by 2012.”

But by his final autumn in office (2015), there were an estimated 940 people sleeping rough in the capital.

Over his tenure, rough sleeping rose by 130 per cent, although the nature of these stats means that even this could understate the true extent of the problem.

Police numbers

Mr Johnson made a number of opaque and downright misleading claims about the strength of the Metropolitan Police while he was mayor of London, which we FactChecked at the time.

At one point he announced: “We are recruiting 5,000 constables over the next three years”, which sounded like a welcome boost to Met police numbers.

He failed to mention that the Met expected to lose 5,000 PCs over three years through natural wastage – all he was promising to do was replace the ones who left.

Figures released to members of the London Assembly show that the Met had the equivalent of 33,404 full-time police officers (not including PCSOs or special constables) in November 2009.

That fell to 32,125 officers on March 31, 2016, shortly before Mr Johnson left office.

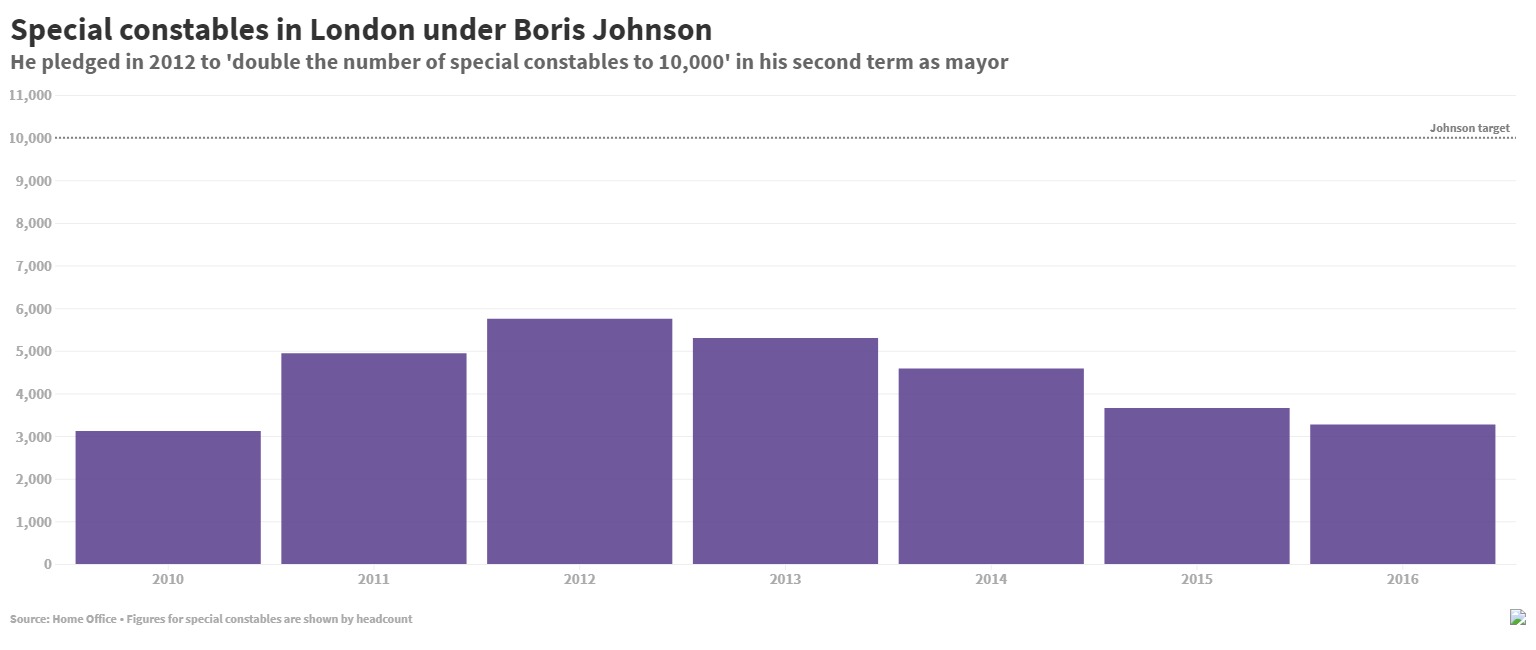

Special constables

His 2012 manifesto promised to ‘double the number of special constables to 10,000′. At the end of his tenure in 2016, there were just 3,271 special constables in the Met, less than a third of his target.

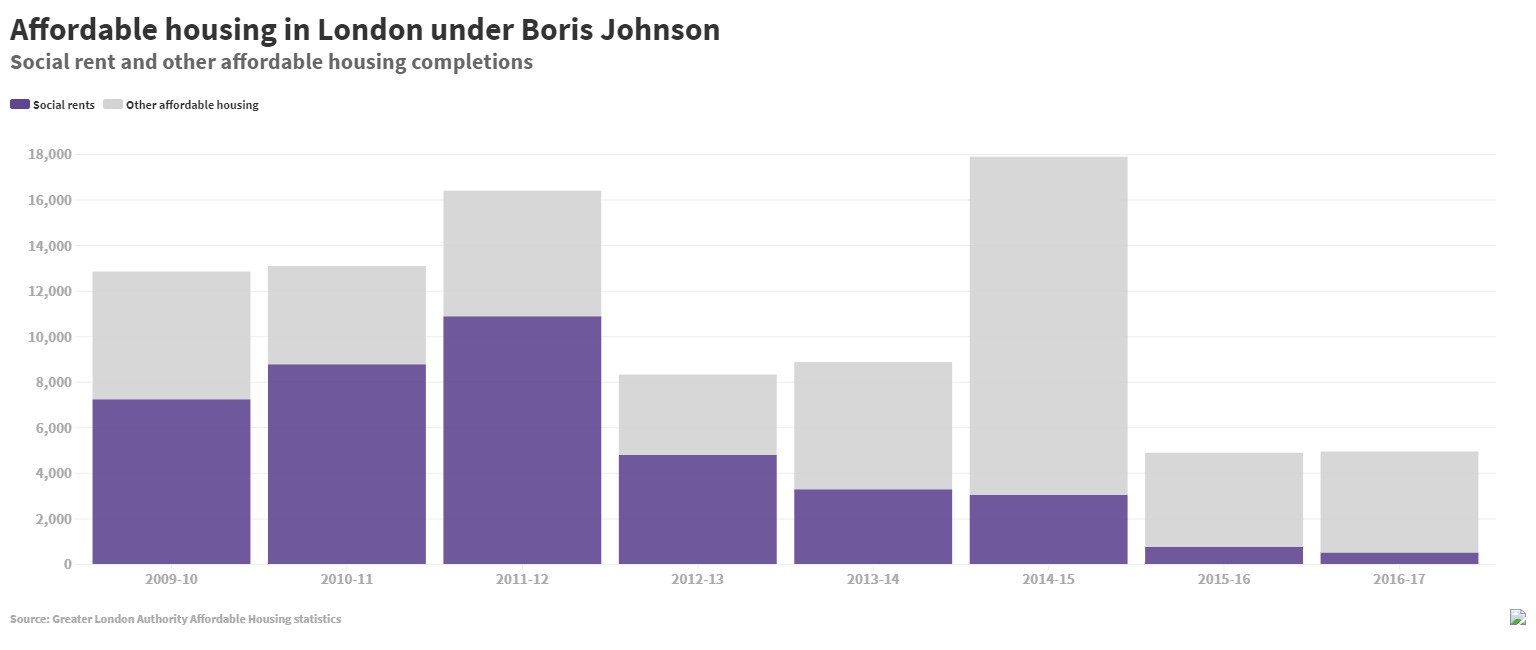

Affordable homes

Mr Johnson set himself a target of building 100,000 new affordable homes in London between 2008-09 and 2015-16.

But he only get elected as mayor in May 2008, and the budget for the financial year 2008-09 had already been signed off by the previous mayor, Ken Livingstone.

If you count from 2009-10 to 2016-17, when he approved the budgets, Mr Johnson just missed the 100,000 target, using the most generous figures available.

More importantly, not all “affordable” housing is created equal, and the kind of housing likely to be made available for London’s poorest citizens plummeted on Mr Johnson’s watch.

The cost of “affordable” rents can be as high as 80 per cent of local private sector prices, and households with an income of up to £90,000 are eligible for “intermediate rent” homes – still defined as “affordable”.

Homes let as “social rent” or the almost-identical “London Affordable Rent” are likely to be among the cheapest. The supply of these kind of homes fell from more than 10,000 a year to around 500 under Mr Johnson:

Water cannon

In 2014, Mr Johnson agreed in a live radio interview to be blasted by water cannon to show their safety. The demonstration never materialised, and in 2018, the machines were sold off at a £300,000 loss to the taxpayer. They had never been used.

Heathrow third runway

Mr Johnson was an outspoken critic of the proposed third runway at Heathrow throughout his time as mayor, describing the proposal as a “mistake”, “self-defeating”, “short-termist” and “barbarically contemptuous of the rights of the population”.

When he returned to Parliament as the member for Uxbridge in 2015, he promised to “lie down in front of those bulldozers” to stop the expansion.

Things came to a head last June when members of the government, including Mr Johnson who was foreign secretary at the time, were required to vote in favour of the project in parliament.

Shortly before the vote, it emerged that Mr Johnson had travelled to Afghanistan and would miss it. He said that quitting the government to vote against the third runway, as his colleague Greg Hands had just done, would “achieve absolutely nothing.”

Did he halve the murder rate?

We should mention Mr Johnson’s claim yesterday that during his time as mayor “we cut the murder rate by 50 per cent”.

He’s talking about homicides, which includes offences like manslaughter as well as murder.

In one year of Mr Johnson’s tenure (2014-15), the homicide rate fell to 12.2 per million, according to our analysis of Home Office and Office for National Statistics figures. That’s 43 per cent lower than it was in the year before he took office. We understand this is the basis of his claim to have cut London’s murder rate by 50 per cent.

It crept up slightly in his final year to 12.9 per million, which means that when Mr Johnson left office, the London homicide rate was 39 per cent lower than he found it.

by Patrick Worrall and Georgina Lee