The worst place in Europe to have a brain tumour?

Cancer Research UK says survival for childhood cancers may have increased hugely in the UK and across Europe, but it masks the fact that some cancer types have not seen such a great improvement.

What is the worst type of cancer?

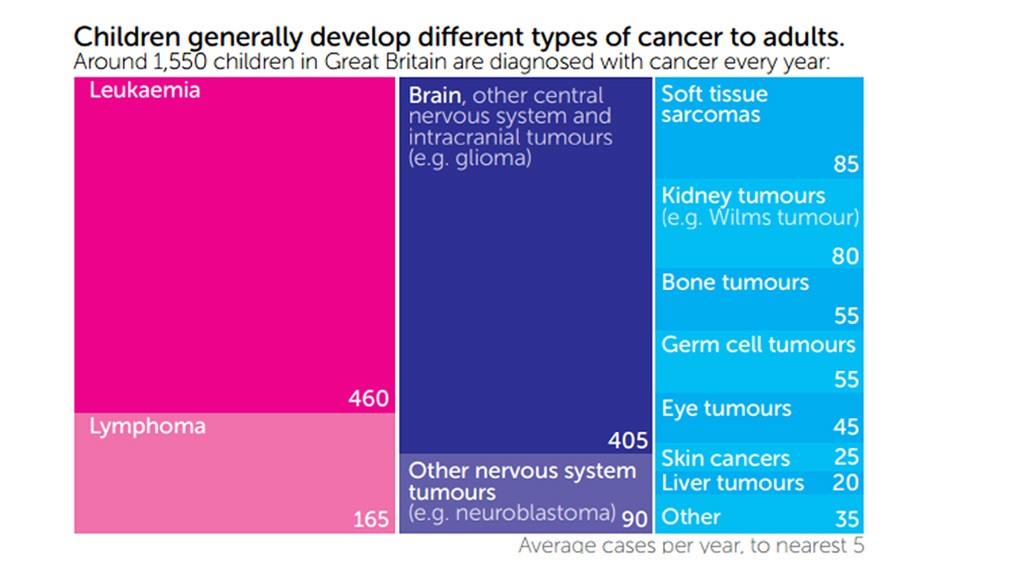

According to Cancer Research, around 400 children under the age of 15 are diagnosed with a brain, other central nervous system (CNS) or intracranial tumour in Britain each year.

These are the second most common group of cancers diagnosed in children in Britain, accounting for more than a quarter (27 per cent) of all childhood cancers.

Brain, other CNS and intracranial tumours are also the most common cause of childhood death from cancer, with almost 100 children dying in the UK from these tumours every year.

Survival rates in Britain

For children, survival rates for brain, other CNS and intracranial tumours have almost doubled since the late 1960s. More than seven in 10 children now survive their disease for at least five years.

Brain tumours may appear to be relatively treatable with an overall survival rate of 75 per cent, but as they are the most common type of tumours, they also account for the highest number of deaths.

And in Europe?

For all childhood cancers diagnosed in the period 1988-1997 by the Automated Childhood Cancer Information System project, five-year survival was highest in northern Europe (77 per cent) and lowest in the Eastern region (62 per cent); survival for the British Isles was roughly in the middle at 71 per cent.

The five-year survival rate for children with cancer in the UK and Ireland between 1995 and 2007 is said to be similar to the European average, according to Cancer Research UK.

However, a study compiled by EUROCARE-5 for the Lancet Oncology, found that although overall survival and cure rates had vastly improved, it was not in all European countries.

Analysing survival rates for 157,499 children aged between 0 and 14 with different types of cancer, it pointed out that while there has been an improvement in survival in some areas, there has been no progress in regards to children with brain tumours, neuroblastoma and sarcomas.

There were also disparities in survival of children and adolescents with cancer across Europe depending on healthcare resources, which widely varied especially in eastern Europe. The survival rate there was 10 to 20 per cent lower than in western Europe, while the UK also lagged considerably behind compared to the national average.

Late diagnosis

Parents of children with cancer often report difficulties getting their children diagnosed. A 2001 study in The Lancet conducted in-depth interviews with 20 parents of children with cancer. Half of them reported some degree of dispute or disagreement with doctors at some point during diagnosis.

According to Dr Sophie Wilne, a paediatric oncologist in Nottingham, referring a child for a brain scan who does not require one creates a lot of “unnecessary anxiety” for families and the patients involved. Referring children who do not need scans also has the knock-on effect of increasing waiting times – meaning that it can take longer for a critically-ill child to get a scan.

Around two thirds of children who survive are left with some form of disability according to the cancer charity. The level and type of disability will depend on the type, size and position of the tumour and how exactly it was treated.

Treatments available across Europe

Many young children (less than three years old) with brain tumours now have chemotherapy to keep their tumour under control until they are old enough to have radiotherapy safely. In some cases, surgery is recommended, and then a course of chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

- radiotherapy

Brain cancer is treated with high energy waves (X-rays), in cases where a tumour cannot be removed.

- chemotherapy

Anti-cancer (cytotoxic) drugs are used to destroy cancer cells. They work by disrupting the growth of cancer cells. The drugs are taken every few weeks up to two years.

A stream of protons – the positively charged particles found in the nucleus of an atom – can be used to zap cancer cells and stop them multiplying.

Questions have been raised over the high cost of the project in the UK, and whether it would deliver value for money. The treatment, however, is already available in Prague.