Why has Britain been unable to deport Abu Qatada?

As France swiftly expels two radical Islamists, Channel 4 News looks at why the British government is finding it so difficult to remove radical cleric Abu Qatada.

The French interior ministry announced on Monday that Almany Baradji, from Mali, and Ali Belhadad, an Algerian, had been expelled on national security grounds.

Almany Baradji, an imam, was accused of preaching anti-semitism and encouraging women to wear the Muslim veil, which is illegal in France. Ali Belhadad, a former prisoner, had allegedly renewed his links with other Islamists.They were returned to their countries of origin without an appeal.

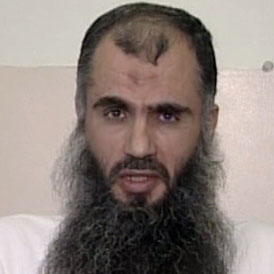

In Britain, Home Secretary Theresa May is trying to deport Abu Qatada, pictured left, to his native Jordan. But he has mounted numerous appeals against extradition.

The UK has always by reputation taken very seriously the risk of receiving an unfavourable judgment from the European court. Stuart Alford, International Bar Association

Abu Qatada, once described as Osama bin Laden’s right-hand man in Europe, has been convicted in absentia in Jordan of plotting explosions there and faces trial if he is returned to Amman. He was granted asylum in Britain in 1994, but was arrested shortly after 9/11 and has spent the intervening years on remand or under surveillance.

Tagged

He was released from prison in February and is on bail, forced to wear an electronic tag and banned from using the internet or telephone.

In January, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that he could not be returned to Jordan because evidence gathered by torture could be used against him.

The ruling represented the first time that the ECHR has found an extradition would be in violation of article six of the European Convention on Human Rights, the right to a fair trial, enshrined in British law under human rights legislation.

Theresa May has travelled to Amman to seek assurances that any future trial would be carried out in a way that satisfies the ECHR.

France and Italy

The case is currently in limbo, and questions are being asked about why the British government cannot deport Abu Qatda, while France, which is also a signatory to the human rights convention, is able to move so quickly against those it considers a threat to national security.

Under the British system, people are not deported until they have exhausted all rights of appeal. In France, removals can be carried out earlier. Almany Baradji and Ali Belhadad have a right of appeal, but they would have to do this from outside France, an unlikely scenario.

France is not the only European country that does not follow the British example. On 27 March, the Italian government, which has also signed the human rights convention, was ordered to pay damages of £12,500 after defying a ruling from the ECHR by deporting a former Islamist prisoner to Tunisia.

The court had said Mohamed Mannai should not be expelled until his appeal had been heard, but after his removal, Rome was not instructed to re-admit him.

‘Immediate threat’

Stuart Alford, co-chairman of the International Bar Association’s war crimes committee, told Channel 4 News that France could argue that the deportations were necessary because of this month’s attacks in Toulouse.

He said this justification could rest on France facing an “immediate threat” following Mohamed Merah’s murder of three Jewish children and a rabbi, whereas no-one was suggesting Britain faced a similiar threat at the moment.

Mr Alford, who has prosecuted for the UN and was an adviser to the judges in Saddam Hussein’s trial, said: “The UK has always by reputation taken very seriously the risk of receiving an unfavourable judgment from the European court. It has always considered due process of law, which includes the right to take a case to the European court as an important part of what the UK stands for.

“When push comes to shove, we tend to fall in line with commitments we have made to various legislative and judicial bodies and when an appeal goes to the European court, we implement what it says. We live with these judgments because that is our system of law, because we have made commitments and brought it into our legislation through the human rights act.” This would remain the case unless Britain amended the human rights act, said Mr Alford.

One reason for Abu Qatada’s success in the courts could be the skills of the lawyer representing him, Gareth Peirce, best known for her work on behalf of the Guildford Four and Birmingham Six.

Adversarial

Mr Alford said “tenacious representation” had an important part to play in Britain’s adversarial legal system. “Because of the nature of an adversarial system that pitches the individual against the state …. there is probably some margin of difference in the way these cases are pursued. The role of a defence lawyer in France and other continental systems is very different because they don’t have an adversarial system.”

Theresa May told the BBC’s Today programme on 23 March: “What I’m working on is getting the assurances that do enable us to deport Abu Qatada. That’s my aim because if I do it in that way then I can assure that the deportation is sustainable. And that’s what I want to ensure, once Abu Qatada is deported from the UK, he remains deported from the UK.”

A Home Office spokesperson said: “We want a lasting solution that means Qatada is deported for good. This case has dragged on for over a decade and we are exploring every legal avenue to get this dangerous man on a plane and out of the UK.”

-

Latest news

-

As India goes to the polls in the world’s largest election – what do British-Indians think?17m

-

Tees Valley: Meet the candidates in one of the biggest contests coming up in May’s local elections4m

-

Keir Starmer says public sector reform will be a struggle7m

-

Nicola Sturgeon’s husband Peter Murrell charged with embezzlement of funds from SNP1m

-

Ukraine might finally get $60billion in American weapons and assistance to defend against Russia3m

-