Tolkien’s Beowulf: a ‘great gift’

The long Hwaet! is over for scholars and Tolkien fans as the Lord of the Rings author’s translation of the Anglo-Saxon epic poem is published after 88 years.

The latest episode in Peter Jackson’s three-part adaptation of The Hobbit has taken almost $1bn worldwide – proof of the enduring appeal of JRR Tolkien’s creations.

But the latest addition to the Tolkien canon is a work of scholarship that has lain unloved in the archives since it was completed in 1926.

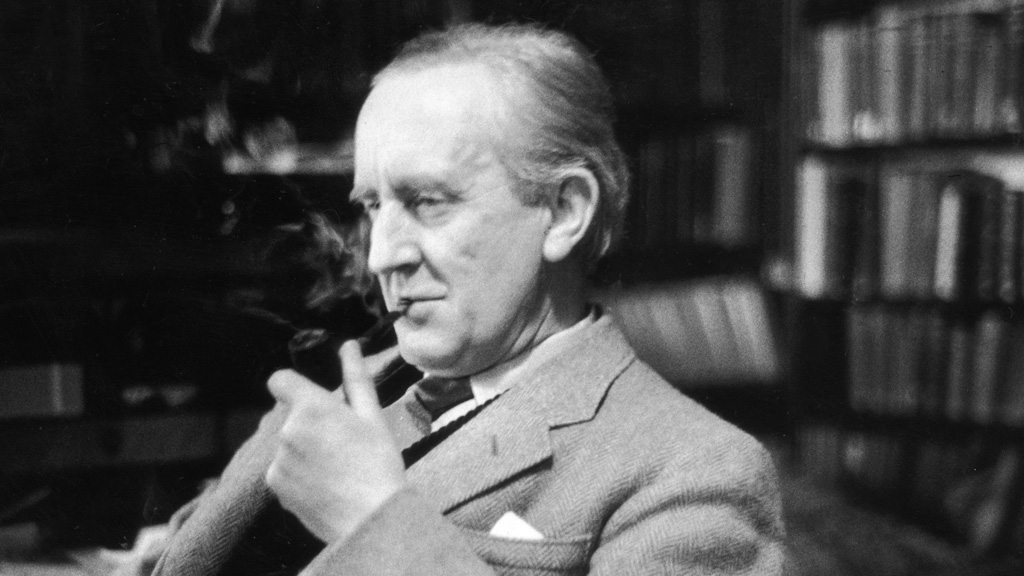

Decades before he achieved worldwide fame through the adventures of Bilbo Baggins, Gandalf and Gollum, Tolkien was a hugely respected scholar, a leading expert on early English literature and ancient languages.

The newly published translation of Beowulf dates from his time as a distinguished professor of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College, Oxford.

Beowulf, the story of a Danish warrior who battles a trio of supernatural monsters, was written around 1000 by anonymous poet. It is the earliest surviving Old English poem and only one manuscript exists, in the British Library.

The story of Beowulf’s struggle against the grotesque Grendel, his evil mother and a fire-breathing dragon has been retold many times, inspiring comic book versions, a 2007 animated fim starring Ray Winstone and Angelina Jolie and a critically acclaimed verse translation by the late Irish poet Seamus Heaney.

Tolkien drew widely from Old English and Norse literature when he created the fantasy world of Middle Earth.

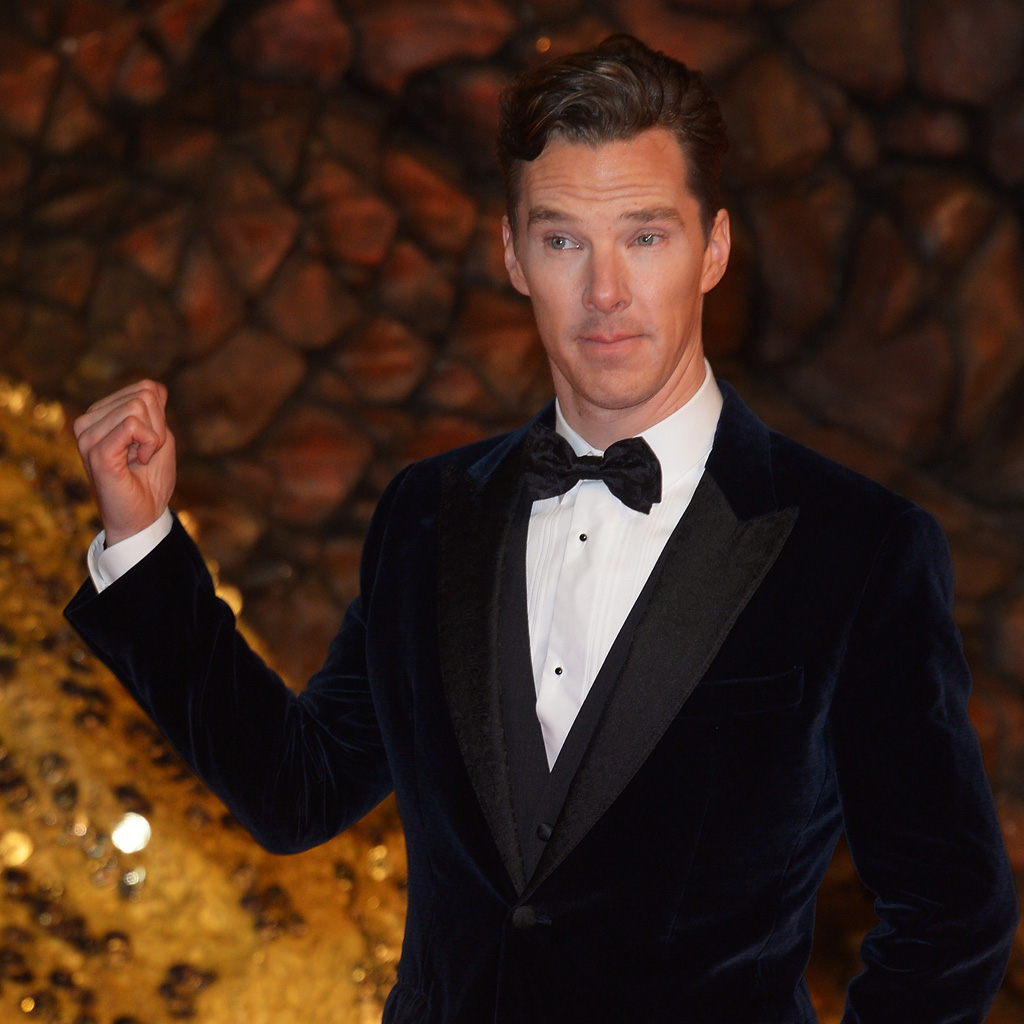

The names of the dwarves who accompany Bilbo Baggins and the wizard Gandalf come from the Old Norse Poetic Edda. And the dragon Smaug, who squats on a fabulous hoard of treasure (played by Benedict Cumberbatch in the Hobbit film trilogy) is modelled on the unnamed “wyrm” who menaces Beowulf.

Tolkien always acknowledged the impact of Beowulf on his work, and in 1936 he gave lecture, Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, which had a profound influence on later study of the poem.

His son Christopher, now 89, who has edited most of Tolkien’s posthumously published work, said: “The translation of Beowulf by J R R Tolkien was an early work, very distinctive in its mode, completed in 1926: he returned to it later to make hasty corrections, but seems never to have considered its publication.

“This edition is twofold, for there exists an illuminating commentary on the text of the poem by the translator himself, in the written form of a series of lectures given at Oxford in the 1930s; and from these lectures a substantial selection has been made, to form also a commentary on the translation in this book.

“From his creative attention to detail in these lectures there arises a sense of the immediacy and clarity of his vision. It is as if he entered into the imagined past: standing beside Beowulf and his men shaking out their mail-shirts as they beached their ship on the coast of Denmark, listening to the rising anger of Beowulf at the taunting of Unferth, or looking up in amazement at Grendel’s terrible hand set under the roof of Heorot.”

Three versions of Beowulf: the dragon attacks

gewát ðá byrnende gebogen scríðan

tó gescipe scyndan

(Old English original)

Swaddled in flames, it came gliding and flexing

And racing towards its fate

(Seamus Heaney translation)

Now it came blazing, gliding in looped curves, hastening to its fate.

(Tolkien translation)

Tolkien’s translation differs radically from Heaney’s in that it is written entirely in prose. The professor makes no attempt to match the poet in echoing the distinctive patterns of stress and alliteration in Anglo-Saxon poetry.

But Tolkien’s vast knowledge of the language of the period means his version is very close to the original in sense, according to experts.

Dr Philippa Semper from the University of Birmingham’s Centre for the Study of the Middle Ages told Channel 4 News: “It is a captivating translation, showing Tolkien’s knack of expressing the sentiment and colour of the Old English as well as remaining more true than most to its grammatical structure and overall shape.

“If you are a Tolkien fan who has listened repeatedly to the recordings of Tolkien reading selections from Lord of the Rings, you will discover that you can hear Tolkien’s voice very clearly through the lines of his Beowulf, and that is a very great pleasure.”

She added: “I think that the story of Beowulf still fascinates readers because it expresses that most basic and yet most engaging of themes: a hero fighting off the monsters. Beowulf’s struggles are to save lives, first of all among the Danes and then among his own people, and so the stakes of the story are high.

The monsters are also archetypally disturbing, from the shadowy creatures that steal men away in the night to the dragon whose fiery rage burns everything before it. Dr Philippa Semper

“The monsters are also archetypally disturbing, from the shadowy creatures that steal men away in the night to the dragon whose fiery rage burns everything before it.

“Combined with this there is in the Old English poem a kind of wistfulness for a lost past in which such stories might have been true, however challenging its monsters might be, that speaks to many of us.

“This new publication, then, it is a great gift to anyone interested in Beowulf or Tolkien. It is unlikely to change the face of current scholarship on the poem in the way that his intervention did in the 1930s, but it provides us with valuable material on his interactions with the greatest surviving poem in Old English.

“Hopefully it will encourage even more people to read the story of Beowulf. And we have reason to be thankful to Christopher Tolkien once again for his work in preparing the text for publication.”

Not all critics have been as complimentary about the translation. In the Telegraph, Jeremy Noel-Tod writes: “This literal rendering is faithful to the formulaic circumlocutions, inversions and amplifications of Old English poetry – a heroic style that evolved to while away a winter’s night, but which loses something when locked into the frigid grammar of a legal document.”

And some commentators have questioned the ethics of publishing work that the late professor showed no desire to publish during his lifetime.

Many others are happy to have another tome to add to their Tolkien collection, with fans using the hashtag #Hwaet on Twitter – the enigmatic opening word of Beowulf, translated as Lo! by Tolkien – to register their glee.