Mladic: another step towards an international rule of law?

Mladic, one of the last cards in the pack of wanted Balkan war criminals, will face justice before the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia. What can the ICC learn from this?

Unlike many others wanted for war crimes or crimes against humanity by the UN, Ratko Mladic is indicted to appear before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) rather than the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Since its creation in 1993 the ICTY – a UN-sanctioned autonomous tribunal based in the Hague – has successfully brought to justice over 250 people accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity and other charges relating to the war in the Balkans.

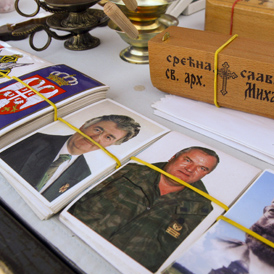

The ICTY issued its indictment against Mladic in 1995, and for 16 years – in common with a number of those sought by the court – he has been able to live as a fugitive with the support of sympathetic nationals and those who still revere him and his cause.

The Success of the ICTY

Since its creation the ICTY, along with the ICTR (Rwanda), has proved an effective although at times criticised court. One criticism has always been that Mladic, among others, was still at large. Despite the court’s specific and expert knowledge of the evidence, bringing the most wanted to the Hague was not within the court’s remit, rather it was reliant on less than sympathetic national security forces.

Mladic was the last “big name” still at large. If convicted, the process might finally bring justice for those who lost friends and relatives in the war’s biggest massacre of 8,000 men and boys in Srebrenica.

He will now be transferred to the Hague, where his alleged crimes will be heard and he will be held in custody until the sackloads of likely witness statements and evidence are picked through by the judges.

The trial will no doubt meet barriers. Radovan Karadzic who was arrested in 2008, continues to question the legitimacy of the court and whether the United Nations ever had the right to create it. These obstructions to the judicial process are similar to those of the most high-profile of those indicted. The former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic – whose case might have lasted for years – died in custody while it was still in progress.

ICC stumbling blocks

Number one on the list of those still at large with an ICC indictment over their head is Omar al-Bashir, President of Sudan. How will a court effectively bring him to trial whilst he resides in a country he still controls? Similarly, if Colonel Gaddafi is captured following a possible indictment, along with other military heads accused by locals of committing war crimes, will he be accountable to a criminal court when he is still an effective head of state?

The question is whether an international court can have a genuine mandate to bring individuals to justice. The ICTY met such criticism when it was created while the Bosnian war was still raging. Only since the fighting ended and the political ramifications of independence were resolved has the court really gained legitimacy.

The ICC is, of course, still in its infancy. The ICTY has been in action for almost 20 years – and that is some indication of how far the International Criminal Court has to go. Bringing war criminals to justice bears no similarity to domestic trials. Involved are matters of state, the testimonies of not tens but thousands of those involved, the legitimacies of war, and the culpability of the individuals under a far less well-defined rule of law.

-

Latest news

-

Laughing Boy: New play tells the tragic tale of Connor Sparrowhawk5m

-

Sewage warning system allows some of worst test results to be left off rating system, analysis shows3m

-

Post Office inquiry: Former CEO didn’t like word “bugs” to refer to faulty IT system4m

-

Israeli soldier speaks out on war in Gaza12m

-

PM’s defence spending boost should be ‘celebrated’, says former Armed Forces Minister4m

-