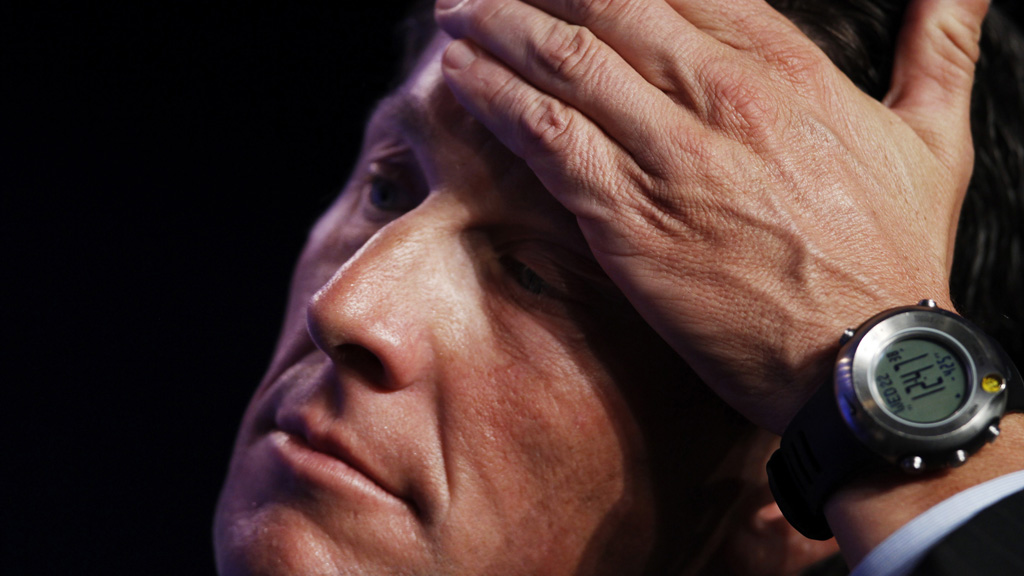

After Armstrong, does cycling have ‘nothing to hide’?

British cycling bosses have distanced themselves from an era in which star cyclist Lance Armstrong was able to head up a “sophisticated doping operation”. So has the sport now cleaned up its act?

Not just a drugs cheat but the lead figure in a “sophisticated doping operation”, involving trafficking. lies and intimidation – the portrait painted of Lance Armstrong has been a damning one.

The US Anti-Doping Authority (USADA) has found that Armstrong, professional cycling’s golden boy for more than a decade, “enforced and reinforced” the doping culture at the US Postal Service cycling team, of which he was the leader, during the “dirtiest ever” era in professional cycling.

But Ian Drake, the chief executive of British Cycling, says the sport now has “nothing to hide”.

“We’ve still got a hangover from a really bad era in the sport,” he said. “At British Cycling we’re proud of our strong and long-standing record in the fight against doping. We’ve got to learn the lessons from the past and focus on where we want the sport to be.”

This year’s Tour de France and Olympic cycling champion Bradley Wiggins said today he was not suprised by the report. “It’s pretty damning stuff. It is pretty jaw-dropping the amount of people who have testified against him.

“It is certainly not a one-sided hatchet job, it is pretty damning. I am shocked at the scale of the evidence. I have been involved in pro-cycling for a long time and I realise what it takes to train and win the Tour de France. I’m not surprised by it…I had a good idea what is going on.”

The report from the USADA, which can be found here, lists evidence of doping by Mr Armstrong every year between 1998 and 2005, covering every year in which he won the Tour de France, road cycling’s top achievement. Mr Armstrong refused to face the charges laid before him by the USADA, which meant a hearing did not take place.

USADA last night published its findings against Mr Armstrong in a 200-page report which included evidence from 11 of his former teammates. Mr Armstrong’s lawyers responded to the report, known as a ‘reasoned decision’, by calling it “a farce”.

“While USADA can put lipstick on a pig, it is still a pig”, the lawyer said.

But has professional cycling dramatically changed since the time of Mr Armstrong’s domination of the sport?

“A good place now”

Many of Mr Armstrong’s teammates at US Postal Service, who were also found to have used, among other things, the banned performance enhancing drug EPO, have released statements today apologising for their conduct and lauding the fact that the pressures of drug taking are no longer around in professional cycling.

American cyclist Christian Vande Velde, who was a teammate of Mr Armstrong between 1998 and 2003, said: “One day, I was presented with a choice that to me, at the time, seemed like the only way to continue to follow my dream at the highest level of the sport. I gave in and crossed the line, a decision that I deeply regret. I was wrong to think I didn’t have a choice – the fact is that I did, and I chose wrong.

“…We’re in a good place now, young riders of the new generation have not had to face the choices that I did, and this needs to continue. By looking at the mistakes of cycling’s history, we have an opportunity to continue to shape its future.”

What is EPO?

EPO, or Erythropoietin, is a hormone that regulates red blood cell production. When injected, it instructs the body to produce more red blood cells. By doing this they improve the blods ability to deliver oxygen to their muscles - thereby improving physical performance - especially in endurance events such as the Tour de France.

A statement from George Hincapie, who cycled with Lance Armstrong over 11 seasons, said: “Cycling has made remarkable gains over the past several years and can serve as a good example for other sports.

“Thankfully, the use of performance enhancing drugs is no longer embedded in the culture of our sport, and younger riders are not faced with the same choice we had.”

However, Nicole Sapstead, director of operations at UK Anti-Doping, warned that drugs cheats, throughout sport, are getting more sophisticated.

“It is getting more sophisticated because they have to be more sophisticated because the ways we use to catch them are getting more sophisticated,” she said.

“What we want to do is make it more difficult, make it so difficult that it becomes more problematic than it’ s worth (for the cheats).”

What am I doing tonight? Hanging with my family, unaffected, and thinking about this. bit.ly/Po6mXT #onward

— Lance Armstrong (@lancearmstrong) October 11, 2012

Ms Sapstead pointed to a number of methods that have been developed since Mr Armstrong’s heyday, such as the National Registered Testing Pool, a register of each country’s elite sportspersons that allows them to be located for testing “365 days a year”, and the Athlete Biological Passport, which monitors an athletes biological variables rather than trying to catch them with drugs in their system.

She also pointed to a team that UK Anti-Doping uses, a mixture of former law enforcement and sports workers, which investigates “persons behind the cheating”, ie those who facilitate doping through activities such as trafficking.

However, she stopped short of saying that the prevalence of doping, across sport in general, is less now than it has been in the last fifteen years.

She said you have to distinguish between those who inadvertantly breaking doping rules, by not being aware of what is banned or what chemicals certain prodcuts contain, and those who are deliberately doping through sophisticated methods.

“Things have got better in terms of telling the inadvertant doper about the risks and consequences of certain products,” she said. “I can’t tell you whether the sophisticated doper is more prevalent or not, but it’s not about trying to work that out, it’s about trying to identify those athletes who are.”

Lance Armstrong: portrait of a drugs cheat

The portrait of Lance Armstrong is not simply of a man who used banned methods to win in his sport. The USADA said the case against Mr Armstrong is “beyond strong; it is as strong as, or stronger than, that presented in any case brought by USADA over the initial twelve years of USADA’s existence”. Below are the charges and the evidence against cycling’s Tour de Force:

Charge One: Use and/or attempted use of prohibited substances and/or methods including EPO, blood transfusions, testosterone, corticosteroids and/or masking agents.

Evidence: A number of former team mates have detailed Mr Armstrong's use of banned drugs, including Tyler Hamilton, George Hincapie, Floyd Landis and Mr Armstrong's masseuse Emma O'Reilly.

Also, five blood samples from the 2009 Tour de France show an usually low level of reticulocytes, immature blood cells, in Mr Armstrong's blood, which could suggest Mr Armstrong had been artificially increasing his blood cell count. Urine sample from the 1999 and 2001 Tour de France were said to also contain evidence of the use of EPO.

Charge Two: Possession of prohibited substances and/or methods including EPO, blood transfusions and related equipment.

Evidence: The USADA cites testimony that Lance Armstrong kept EPO in the fridge at his villa in Nice, that he was seen injecting the drug in his room at the Vuelta a Espana in 1998, that he used to ask his wife to wrap cortisone pills in tin foil for him, and that on many occasions teammates would go to see Armstrong in order to be given prohibited drugs.

Charge Three: Trafficking of EPO, testosterone, and/or corticosteroids.

Evidence: As with charge two, the USADA received statements that members of Mr Armstrong's team would be sent to him in order to receive dugs, from EPO to testosterone patches, and that he also mailed EPO to one of his teammates. USADA also said that Armstrong put pressure on members of his team to use performance enhancing drugs, telling Vande Velde in 2002 that he would lose his place on the team if he did not more strictly adhere to the doping programme.

Charge Four: Administration and/or attempted administration to others of EPO, testosterone, and/or cortisone.

Evidence: Statements on Mr Armstrong administering drugs to others include that he gave Mr Hincapie EPO in 2005 and that he "squirted" a misture of olive oil and testosterone into Mr Hamilton's mouth.

Charge Five: Assisting, encouraging, aiding, abetting, covering up and other complicity involving one or more anti-doping rule violations and/or attempted anti-doping rule violations.

Evidence: The USADA cited emails from Mr Armstrong to former teammates, ahead of the USADA, asking them to sign affadvits "affirming that there was no 'systematic' doping" on the US Postal Service team. USADA that it was aware of Mr Armstrong's legal team discouraging witnesses from testifying. Statements from various cyclists say that Mr Armstrong had threatened them after they spoke out against doping, against Mr Armstrong, or against people he knew.

In 2004, Filippo Simeoni, said that Mr Armstrong told him "I can destroy you". Tyler Hamilton has testified that, in 2011 after giving information on Mr Armstrong's doping, Mr Armstrong said: "I am going to make your life a lving... f***ing... hell". There was also evidence, the USADA said, that Mr Armstrong had sent text messages to the wife of a teammate that were intimidating.

-

Latest news

-

Taylor Swift’s new break-up album breaks records3m

-

NHS trust fined £200K for failings that led to death of two mental health patients3m

-

Sunak vows to end UK ‘sick note culture’ with benefit reform3m

-

‘Loose talk about using nuclear weapons is irresponsible and unacceptable’, says head of UN’s nuclear watchdog3m

-

‘There wasn’t an Israeli attack on Iran,’ says former adviser to Iran’s nuclear negotiations team7m

-