British forces in Afghanistan: why are we there?

Britain’s presence in Afghanistan has seen military deaths soar beyond 300. But what lies next for UK forces? A former commander and soldier write for Channel 4 News about future strategy.

In the UK the human cost of the Afghan war has come to be signified by flag-draped coffins filing through Wootton Bassett. It is the town in Wiltshire through which bodies are repatriated after being flown home from Afghanistan to RAF Lyneham.

The grim milestone of 300 deaths was reached in June 2010, when 23-year-old Paul Warren, of 40 Commando Royal Marines, was killed in an explosion in Sangin.

Prime Minister David Cameron said: “It is desperately sad news, another family with such grief and pain and loss.

We are paying a high price for keeping our country safe. We should keep asking why we’re there and how long we must be there. David Cameron

“Of course the three hundredth death is no more or less tragic than the 299 that came before. But it is a moment for the whole country to reflect on the incredible service and sacrifice and dedication that our armed services give on our behalf.”

More from Channel 4 News: Ten-point plan for Cameron and Afghanistan

“We are paying a high price for keeping our country safe, for making our world a safer place. We should keep asking why we’re there and how long we must be there.

“The truth is we’re there because the Afghans are not yet ready to keep their own country safe and to keep terrorists and terrorist training camps out of their country.

“That’s why we have to be there. But as soon as they’re able to take care and take security for their own country that is when we can leave.”

Why the UK cannot pull out of Afghanistan, by former Afghan commander Colonel Richard Kemp

Despite the tragic landmark of 300 British dead, former British forces commander in Afghanistan Colonel Richard Kemp tells Channel 4 News the UK cannot afford to leave the country until its objectives are achieved: "The death rate in Afghanistan seems shocking. But casualties are a brutal reality of all wars. And compared to many previous conflicts the figures in this nine year campaign are low.

"In the Falklands we lost over 250 troops in under three months. Almost 700 British soldiers were killed during the three years of the Korean War. And on average 178 died every single day in the six years of the second world war.

"Even in the Northern Ireland police action, in 1972 alone we had as many killed as in the bloodiest year in Helmand.

"But every soldier's death is a tragedy. The end of each individual's hopes and dreams for the future, and a whole family's life shattered forever.

"We should not inflict such pain and suffering on so many people without good cause. As we pass this latest horrible milestone, should we therefore be calling for the withdrawal of our forces?"

Read more

Both relief and military experts have told Channel 4 News there is growing evidence of “targeted assassinations” by the Taliban. As foreign soldiers hunt insurgents – and are hunted in return, the Taliban is also setting its sights on fellow Afghans: those seemed to be collaborators and informants.

The west’s problem – as it was in Iraq – seems to be that people are as likely to blame us for bringing the war to their neighborhood as they are likely to blame the perpetrators. Stephen Grey

The men signing up to the burgeoning police force and Afghan army. And as the Taliban’s power grows, factions appear and local chiefs hunt their rivals.

Stephen Grey, Author of Operation Snakebite told Channel 4 News: “Civilians are everywhere the first casualties in this war; The question we have to ask ourselves is when the Taliban commit such atrocities, if it was them behind this, like the wedding attack or the hanging of a seven year old, why doesn’t the country rise up and reject them?

“The West’s problem – as it was in Iraq – seems to be that people are as likely to blame us for bringing the war to their neighborhood as they are likely to blame the perpetrators.”

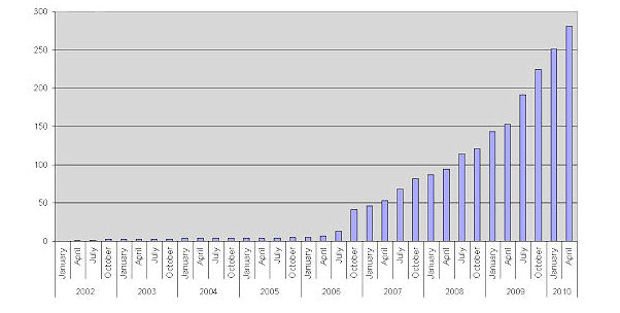

UK's Afghan war in numbers

9,500 British troops stationed in Afghanistan.

335 British soldiers killed in Afghanistan to date.

108 soldiers killed in 2009 - 91 died in action, 16 died of wounds and 1 accidental death.

1 British servicewoman killed in Afghanistan. Corporal Sarah Bryant (pictured) was killed whilst travelling in a Land Rover with three SAS reservists - Cpl Sean Reeve, L/Cpl Richard Larkin and Pte Paul Stout, who died on patrol on 19 June 2008.

388 seriously injured or wounded casualties since October 2001 to summer 2010.

10 18-year-old soldiers have been killed so far.

22 - the average age of British casualties.

51 - The age of the eldest serviceman to have been killed. Sr Aircraftman Gary Thompson rejoined the military services as a reservist in 2005.

34 - the percentage of soldiers killed who were aged between 20 to 25.

8 June 2008 - the date the 100th death mark was passed. Private Nathan Cuthbertson, Private Daniel Gamble and Private Charles Murray of 2nd Battalion The Parachute Regiment were killed in Helmand Province by a suicide bomber.

16 August 2009 - the date the 200th death mark was passed. Private Richard Hunt was part of a vehicle patrol that was hit by a roadside bomb near Musa Qala in Helmand Province on 13 Aug. Died at the Royal College of Defence Medicine in Selly Oak West Midlands two days later.

20 June 2010 - the 300 UK death, Royal Marine Paul Warren.

Nine years, three PMs, two US presidents

The US-led war in Afghanistan came in direct response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks on America by al-Qaida, which killed nearly 3000 people.

The conflict began on 7 October 2001 with Operation Enduring Freedom.

President George W Bush’s key aim was to destroy al-Qaida “safe havens” in Afghanistan and to arrest or kill the group’s spiritual leader Osama bin Laden.

The secondary aim was to bring down the al-Qaida-friendly Taliban, which had imposed an ultra-strict Islamist regime on the country since 1996.

President Bush was fully backed by the UK’s Tony Blair who stood “shoulder to shoulder” with his counterpart – and so British forces launched Operation Herrick, the codename for all UK operations in Afghanistan.

The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was also established, made up of troops from 42 countries. It is now controlled by Nato.

The war changed between 2002 and 2007 from open clashes between coalition forces and Taliban fighters to guerrilla warfare, increased suicide bombings and the rise of the improvised explosive device (IED).

In the first five years the vast majority of coalition deaths were American. Only five UK personnel died between April 2002 and early March 2006.The UK toll began to rise quickly when British troops were deployed to Helmand in 2006.

When Gordon Brown became PM in 2007 he said he had “no truck with anti-Americanism”. He pledged to “refocus” the mission and to speed up the training of Afghan soldiers.

President Obama replaced Bush in 2009 and in December of that year pledged an extra 30,000 US troops to Afghanistan with the aim of “finishing the job”. Mr Obama also set out a timeline for the start of withdrawal in summer 2011.

Gordon Brown said in January 2010 he believed victory was 18 months away.

However, Afghan President Hamid Karzai said his forces would need help from western allies until 2025.

David Cameron became prime minister in May 2010 and said he wanted all British soldiers to be home before the next general election in 2015.

Military might cannot win alone, writes Patrick Hennessey

As the number of British soldiers killed in Afghanistan rises, author and former soldier Patrick Hennessey writes for Channel 4 News that the war strategy faces a significant turning point:

"In 2007 I spent seven hot months in Helmand as a platoon commander in 12 Mechanized Brigade at what was, in retrospect, a small turning point in the current conflict.

"12 Brigade had more man and firepower than the brigades that had come before us and found themselves effectively under siege, but we were insufficiently manned and resourced to do the intensive and productive counter-insurgency work on which subsequent brigades have been engaged.

"The enemy had yet to resort to IEDs as his primary means of inflicting casualties, and our movement was relatively free, if invariably accompanied by an open fight. To use the unfortunately accurate phrase of one officer, we were mostly "mowing the grass".

"We handed over to 52 Brigade, who were commanded by then Brigadier Andrew Mackay who, with Stephen Grey last week, outlined for Channel 4 News a 10 Point Plan for the prime minister's agenda on what was to be one of his new government's top priorities: Afghanistan."

Read more