Alternative Vote: All bets are off

As a Tory MP tells Gary Gibbon the AV referendum could break the Coalition, political analyst Greg Callus looks at the high stakes for Lib Dem Leader Nick Clegg.

If the upcoming national referendum on the Alternative Vote (AV) were to allow voters to choose “Don’t Know”, then a campaign to support this answer would stand a reasonable chance of winning.

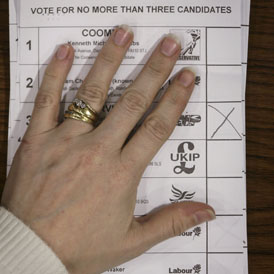

Electoral reform might have been the central pivot of the Coalition Agreement back in May, but for those unencumbered by passions of a psephological nature, the method by which we elect MPs is not always considered a matter of great import.

Nonetheless, the very nature of our democracy being at stake, there are three questions that are worth asking as we head into the final 6 weeks of the campaigns:

1. Which side is more likely to win the referendum?

2. What might be the effect of a No victory?

3. What might be the effect of a Yes victory?

Which side is going to win the referendum?

The matter of a likely winner is incredibly tricky. In most elections, you could turn to the reputable pollsters (and if so-inclined, the bookmakers) for a reasonable guide to a likely winner. Certainly some interesting polling has been done, but the caveats threaten to swallow the results.

This is not like a General or European election, where party membership and political affiliation are good markers for how someone will vote. Interest is comparatively low, turnout will be variable, and the pollsters have little track-record of asking this specific question about this specific type of voting reform.

As a general rule, referenda are won by turnout rather than by convincing a majority that you are correct. Enthusing your base, and introducing doubt into the supporters of the other side, are the means by which a campaign can win – unless one side has a massive lead over the other (60-40 or greater) then a referendum is a betting man’s crap shoot – it is far too susceptible to whomsoever should turnout on the day, and their reasons for doing so, for the polling to be a reliable guide so far in advance.

All elections are, to a greater or lesser extent, ways of expressing support or (more usually) opposition to the Government. This referendum will be no different.

There are also elections that day for the devolved legislatures in Edinburgh, Belfast and Cardiff, and the majority of English local authorities will be facing voters as well. This may boost Celtic vote share as a proportion of the active UK electorate, suggesting a slight left-lean on the general turnout. But the nationalist parties in Holyrood and the Senedd are likely to face a Labour Party able to use its new-found status as Opposition to a Tory Government in Westminster as a springboard once again. If a group are more likely to turnout, it is Labour voters, with all the confusion for the AV campaigns that they entail.

Conservative voters are largely opposed to AV, though some (especially the UKIP-leaning types) are a little unsound in their support for First Past the Post (FPTP). Lib Dems are much more full-throated for electoral reform (obviously), but Labour voters seem to mirror the country at large – they are split tripartite between those in favour, those opposed, and those who are unsure.

Tory MP Peter Bone says in a piece on Channel 4 News tonight that "it's absolutely a possibility" that if the Yes campaign wins the AV referendum Tory MPs could try to pull down the Coalition and force a General Election in the window before the new voting system could be brought in, writes Gary Gibbon.

The plan would be that the Tories could then win an outright majority on first past the post with a manifesto commitment to stick with that system, burying electoral reform for many years to come.

One Tory Cabinet Minister I mentioned that to said that the voters "wouldn't forgive" Tories for such a self-interested act in the middle of an attempt to close the deficit.

What it tells you though is a mood abroad amongst some Tory MPs who are seriously concerned that the Yes campaign is running away with this - Peter Bone says he thinks it is "theirs to lose".

Read Gary Gibbon's blog - AV referendum: Could it break the Coalition?

Unless we see significantly differential turnout, it will be Labour voters who will decide. Will they seek to punish the Lib Dems for enabling a budget-slashing Tory government, or will they dream of a new Lib-Lab alliance capable of keeping the Conservatives out of power for a generation?

In current climate, I suspect the latter is less likely – all elections are, to a greater or lesser extent, ways of expressing support or (more usually) opposition to the Government. This referendum will be no different.

Combined with this, the innate conservatism borne of a new Government, suggesting reform of such hardy perennials as the NHS and the BBC, and I wonder how susceptible the floating Labour voter might react in the privacy of the polling booth? It has long been speculated whether the 1975 EC Referendum would have been won by Europhiles if it had been held to ask whether the UK should enter the EC, rather than retrospectively asking the electorate for permission to stay. I suspect not. If the polls (with Yes and No shares re-percentaged to exclude Don’t Knows as by Mike Smithson over at PoliticalBetting.com) are still close with a week to go, I’d plump for the No camp.

What if the No campaign wins?

So if the No campaign wins, what happens? In theory, very little – it would be a victory for the status quo. The remainder of Nick Clegg’s constitutional reforms will still go ahead, and the 2015 General Election will be run on First Past The Post rules as per usual. There will be fixed-term Parliaments, a less-appointed House of Lords, and 50 MPs will see their seats abolished and boundaries reformulated to reduce discrepancies in population.

Of course, that reflects merely the theory. In reality, the major concession of the Coalition Agreement will have been lost, the Deputy Prime Minister fatally embarrassed, the Liberal Democrats who have avoided Stockholm Syndrome and/or the trappings of high office will demand immediate cessation of the Coalition, and the chances of the more controversial policies passing (NHS reform, tuition fee hikes etc) will be radically reduced.

If the referendum is lost, it is difficult to imagine the result not being cast as a rejection of electoral reform per se. Lord Owen’s declaration of support for “No to AV, Yes to PR” is principled, cogent, and likely to doom proportional representation to at least a decade or two of frustration. Not that it is much more likely to be tabled as a serious proposal even if the Yes campaign wins (can you really scrap a system after only an election or two?). But an AV victory could allow for AV+ (proportional top-ups based on party lists, as is done at Holyrood and the Senedd) not-so-many years down the line.

Nick Clegg would be under immense personal pressure from his party. Even taking them into Government with the Conservatives made many party members unhappy, and Lib Dem voters are fewer in number if the opinion polls are to be believed.

Many Lib Dems were equally annoyed that their one shot at electoral reform was not to be PR or even AV+, so to fail to win even AV will bode ill for Clegg’s leadership. It is difficult to ascertain what benefit the Lib Dems would derive from staying in a deficit-reducing government if they lose the referendum, beyond avoiding the verdict of their 2010 voters at a new General Election.

What if the Yes campaign wins?

But what about a Yes victory? I suspect that we would actually see very little difference for a couple of elections. Behaviours are slow to change, and I’d expect a non-negligible minority of voters would not use their alternative votes. Subtract as well the voters who would support first- or second-placed parties in their constituencies, and the number of voters casting 2nd preferences that are actually counted could be fairly limited – perhaps 15 per cent of all voters. That won’t generate significant changes to the composition of the Commons.

Not only voters will be a little slow to react. Politicians too might consider that the wholesale redrawing of constituencies (the abolition of 50 seats, the re-districting of almost all) will have a far greater impact on their chances of re-election, than the subtle re-positioning needed to secure second preferences from adjacent parties. Don’t expect even the major parties to have the detailed demographic data and political research enjoyed by the Democrats and Republicans in the US, who also enjoy a more linear political spectrum than the UK.

Beyond a small-but-deliberate shift to the centre by all but the most maverick MPs, the process of making candidates more vanilla-flavoured will take a few elections before it can be pronounced epidemic. As long as the candidate’s position is not so repugnant as to invite the revulsion of the third party voters, few campaigns will need to re-position their pitches in anything like the way demanded by new boundaries.

What will change is that, over time, the national campaigns will need to re-examine where they deploy their resources. The very definition of a safe seat will change (though they will certainly still exist, but in perhaps reduced numbers) – instead of the absolute (x-thousand votes) majority, the Commons will see a split between the first-round victors and those who relied on re-assigned votes to tip them over the 50 per cent threshold. The first-rounders will be likely fewer in number than those MPs traditionally thought of as being “safe-except-in-a-landslide”, and so expect perhaps a greater degree of caution-trumping-tribalism from front-benchers developing over time.

Coalition agreements mean compromise, and as long as there are smaller parties bargaining with larger parties, the issue of electoral reform and proportional representation will be alive.

More importantly, how would parties draw up their target seat lists? At the moment, an absolute majority threshold is a fairly good guide, with some additional factors (pavement presence, local authority control, personable candidates) tinkering around the edges. Those decisions become harder if AV passes in May.

If you are Labour, do you spend money where you are in 2nd place but less likely to overhaul (eg 48% Con v 41% Lab v 4% UKIP) or on the seat where you are in third, but just behind a similar party (40% Con v 26% LD v 25% Lab)? If the safe seats list is slightly modified, the list of target seats is likely to be transfigured, and the list of hopeless seats utterly mutilated.

Although AV is not a proportional system – and it is theoretically possible that landslides could be exaggerated rather than constrained – the majority of election outcomes will appear more proportional than at present. This means a higher likelihood of hung Parliaments and thus Coalition agreements. Coalition agreements mean compromise, and as long as there are smaller parties bargaining with larger parties, the issue of electoral reform and proportional representation will be alive.

As mentioned, it would take some glorious chutzpah for the Lib Dems to demand a referendum on STV or pure PR if the 2015 General Election didn’t produce an overall majority, but more modest moves towards AV+ and in-time STV would become staples of coalition negotiations in time.

The final interesting issue is how minor parties might fare. Currently, minor parties and independents are trapped in a vicious cycle – unlikely to win, their natural supporters don’t want to waste their votes on them, so they appear less popular than they in fact are, and so they are perceived as unlikely to win. AV could see this work the other way.

Knowing that you could afford to support (eg) the Pirate Party, and yet still determine whether Labour or the Tories won your seat gives a massive boost to smaller campaigns. They can campaign to garner merely symbolic support, that – once established – can then be used as a springboard to mounting a serious challenge. This fragmentation of the vote would be an interesting process to observe over the decades – mirroring the way in which the growth of parties such as UKIP and the Greens has always ridden the PR elections for the European Parliament.

Over time you would see the viability of smaller, single-issue or more radical parties grow disproportionately. This is not to scaremonger that the BNP would be likely to win a substantial number of seats – the interchange of second preferences amongst the major parties will likely act as a fairly effective block on more extreme victories – but they and similarly small-but-established parties would likely see a noticeable vote share in early rounds, as has been demonstrated in the French Presidential elections. Success follows the perception of success, and AV helps the hopeless with the latter.

Summary

So if AV is passed, little will change at first. MPs will – and should – worry more about boundary changes and elected peerages than pitching for 2nd preferences in the first few cycles. Over time, though, we will likely see a shift to the mainstream centre in terms of candidate and policy homogeneity, offset by a fragmentation of party loyalty and first-vote allocation towards smaller and often more radical parties. Coalitions will become more common, though likely most elections would still render overall majorities or near-majorities.

Where AV has the potential to make the biggest impact, though, is the way in which elections are fought – safe seats and target seats will be categorised and fought in completely different ways, funds allocated perhaps according to regional strategies, and deeper, more intrusive databases of voters will become the essential tools of campaign management, as parties have to discern ever-more-complex second preferences and “Get out the Vote” strategies to offset the growing blandness and inoffensive nature of manifesti. Voters will change allegiances, politicians will change their images, but campaigning will be forced to reform completely or be rendered embarrassingly old-fashioned.

It is far too early, and far too brave, to predict what might happen on 5 May, let alone in the elections that follow, but however ill-founded the prognostications there should be consensus on one matter: in electoral reform at the very least, there is an alternative.

-

Latest news

-

As India goes to the polls in the world’s largest election – what do British-Indians think?6m

-

Tees Valley: Meet the candidates in one of the biggest contests coming up in May’s local elections4m

-

Keir Starmer says public sector reform will be a struggle7m

-

Nicola Sturgeon’s husband Peter Murrell charged with embezzlement of funds from SNP1m

-

Ukraine might finally get $60billion in American weapons and assistance to defend against Russia3m

-